Volume 19, Issue 1 (1-2022)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2022, 19(1): 54-59 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghorbani Z, Imani E, Hoseini Teshnizi S. Effect of Self-Care Training Based On VARK Learning Style Preference on Blood Pressure of Patients with Hypertension. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2022; 19 (1) :54-59

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1276-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1276-en.html

1- Student Research Committee, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, Iran

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, ,eimani@hums.ac.ir

3- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, Iran

2- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, ,

3- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 693 kb]

(2264 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4007 Views)

Full-Text: (709 Views)

Highlights:

What is current knowledge?

Considering the importance of high blood pressure as a cause of ischemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke and kidney dysfunction, it is necessary to implement a self-care program to reduce blood pressure in patients with hypertension.

What is new here?

Self-care training based on VARK learning style preference is effective in lowering blood pressure of patients with high blood pressure.

Introduction

With the rapid social and economic development, lifestyle changes, and aging, high blood pressure has become one of the most important public health issues in the world (1). In 2000, about 972 million people worldwide (around 16%) were living with hypertension, which is anticipated to increase to 4.9 billion people (around 60%) by 2025 (2). Today, the prevalence of this disease has been estimated to be 29.5% in the Eastern Mediterranean region and 22% in Iran (3). The World Health Organization reports that high blood pressure is responsible for 62% of cerebrovascular events and 49% of ischemic heart disease, and causes approximately 7.5 million deaths per year (12.8% of all deaths) worldwide (3,4). Despite the high risk of complications, no much attention has been paid to treatment of hypertension, especially in patients (5). High blood pressure is often asymptomatic, and almost half of the patients are unaware of their disease. The absence of symptoms in the early stages of the disease and the slow onset of complications hiders timely engagement of the patient in the treatment process (either pharmacological or non-pharmacological) (5, 6).

Lack of awareness about high blood pressure is an important challenge in controlling the disease (7). Risk factors for high blood pressure include smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, overweight, sedentary lifestyle, lipid disorders, and high stress. Motivating and educating patients about their illness are the key factors that can be beneficial for them to cope with these risk factors (8). Patient education is a useful tool to improve this knowledge, as it helps patients to improve their lifestyle and promote adherence to medication. Therefore, educational interventions play an important role in the management of hypertension (9). The World Health Organization has recommended patient education as an important strategy to improve patients' active participation in the disease management process (10).

In recent decades, it has been suggested that educators should adapt their teaching style to the specific learner's preference to increase effectiveness of teaching (11). Learning styles refer to the preferred methods of a learner for understanding, absorbing, and interpreting information (12). In fact, learning style is a sensory method by which people prefer to acquire new information (13). People learn to use different strategies to turn an educational message into long-term memory (14). When information is provided using learners' preferred learning styles, educators are better able to communicate with learners, which in turn improves learning (15). Nurses' awareness of learning styles can help them adjust the way of providing educational content in order to strengthen patients' understanding (16). Among the various tools used for determining learners' learning style, the visual, aural, read/write, and kinesthetic (VARK) learning style's questionnaire developed by Neil de Fleming (1987) has good validity and reliability. The results of this questionnaire can help the instructor to choose the most effective method of providing information (14).

Since a limited number of studies have investigated the effect of individual preferred learning style in the field of patient education, this study was conducted to determine effects of self-care training based on the VARK learning style preference on blood pressure of hypertensive patients.

Methods

A semi-experimental study with pretest-posttest design was carried out on 44 patients with hypertension who were referred to six comprehensive health centers in Bandar Abbas (South of Iran) from January to December 2019. Sample size was determined as 40 using the sample size formula to estimate the average of a community taking into account α=0.05, power of 80% (ß=0.20), S=32.5, and d=25 in MedCalc software. Considering the possibility of drop outs, 10% was added to the sample size. After receiving approval from the ethics committee of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.HUMS.REC.1397.261), six health centers in Bandar Abbas (South of Iran) were selected using simple random sampling method. Then, 44 patients with hypertension were selected through convenience sampling method. Informed consent was taken from the participants after explaining the research objectives. Then, based on their learning style preference, the subjects were allocated into four intervention groups including; visual (n=12), aural (n=17), reading/writing (n=8), and kinesthetic (n=7) groups (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria were literacy, no vision or hearing problems, being diagnosed with essential hypertension (stages 1 and 2 hypertension) for at least six months, age of over 18 years, and no learning disability due to mental problems or psychiatric disorders. Data were gathered using a demographic characteristics form (age, sex, level of education, marital status, income level, employment status, smoking, underlying diseases, and drugs/substances) and the VARK learning style questionnaire. A blood pressure monitor and a stethoscope were used to measure blood pressure.

The VARK questionnaire, as a learning preference assessment tool, consists of 16 four-choice questions that can be answered in a short period. All choices correspond to the four sensory modalities including visual, aural, reading/writing, and kinesthetic modes. For each question, the respondents must choose the option that best describes their preferred learning style. If more than one choice matches their preference, they can select more than one option. Depending on the responses, their preferred learning style will be determined (17). In this study, the seventh version of this questionnaire was used, and its reliability was confirmed by obtaining a correlation coefficient of 0.81.

A Richter mercury sphygmomanometer (Diplomat, Germany) and a Richter stethoscope (Germany) were used for measuring blood pressure. Their reliability was confirmed by retest method with a correlation coefficient of 0.93. Blood pressure was measured by a researcher (observing all JNC7 criteria in how to measure blood pressure) from the right hand of patients in sitting position. The subjects were advised to be inactive and not consume heavy food, coffee, and medicine for half an hour before measuring blood pressure. Blood pressure was measured on empty balder after five minutes of rest in a quiet room. To reduce error in measuring blood pressure, calibration was performed by a medical engineer, and blood pressure of all patients in all stages was measured by one person. The trainings were designed and implemented in four, sixty-minute sessions based on the learning style preference of each group (Table 1) (18). The teaching content and methods of education were used according to the learning style of each group (Table 2). To evaluate the effect of educational intervention, the systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured twice, before the intervention and two months after the intervention. Thus, before the first training session, each person's blood pressure was measured and the average of three recent measurements was considered as the baseline (pre-intervention) blood pressure. Two months after the end of the educational interventions, patients' blood pressure was measured four times with an interval of one week between measurements, and the average number of these measurements was recorded as the post-intervention blood pressure

Data were analyzed by using SPSS 16 software. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the frequency of data. One-way analysis of variance was used for intragroup comparison of quantitative variables, and paired t-test and Wilcoxon test were used for comparison of quantitative values (systolic and diastolic blood pressures) before and after the intervention. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Learning style preference of patients is shown in figure 2. The mean age of subjects in the visual, aural, reading/writing, and kinesthetic groups was 60.08±8.71, 58.17±8.59, 52.37±12.59, and 55.57±9.03 years, respectively. The results of one-way analysis of variance showed no significant difference in the mean age of the subjects between the study groups (P=0.329).

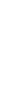

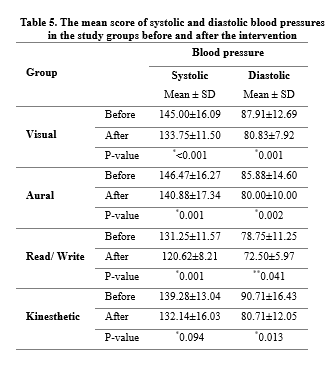

Patients in all four groups were homogeneous in terms of other sociodemographic characteristics (Table 3). Most of the patients were married (75%), homemaker (36.4%), with high school education (36.4%) and sufficient income (53%), and no history of opium use (54.5%). The majority of subjects had an underlying disease (86.4%).

According to the results, after the educational intervention, the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures of all patients reduced significantly (Table 4).

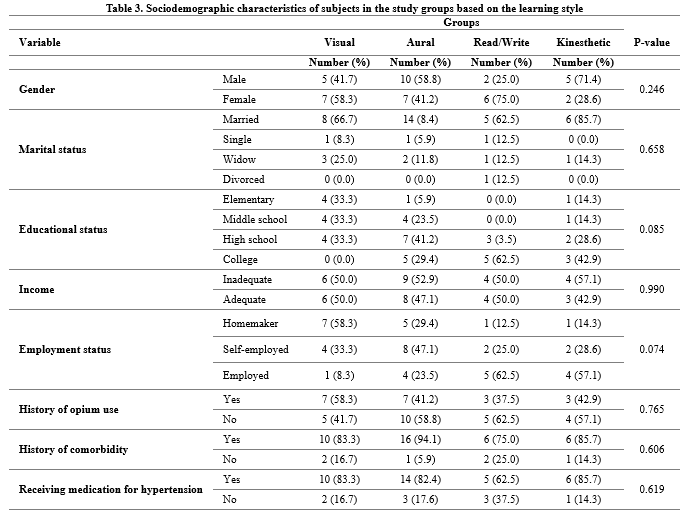

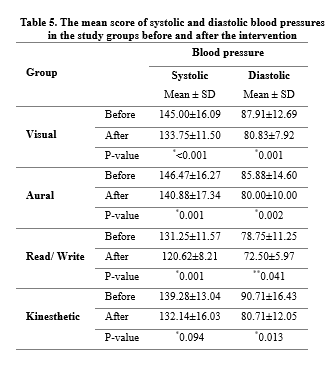

The mean systolic blood pressure after the intervention change notably in all groups (P<0.05) except in the kinesthetic group (P>0.05). In addition, a significant difference was observed in the mean diastolic blood pressure of all patients after the intervention compared with baseline (P<0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

The results of the study showed that the VARK learning style training program significantly reduced the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures of patients with hypertension. To our knowledge, this study is the first to employ an educational method based on the VARK learning style in order to reduce blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Similar to our study, Grebner et al. (2015) conducted a pretest-posttest study to investigate the impact of teaching through learning styles on adult health literacy in central Illinois, USA. The results of their study showed the favorable effect of using this educational method in promoting adult health literacy (19). Anbarasi et al. (2014) conducted a pretest-posttest study to investigate the effect of teaching respiratory physiology based on learning style on students' learning in India. The results of their study showed that people who were trained based on their own learning style scored better than those who were trained only via lectures (20). In a study by Saleh Moghadam et al., training-based learning style method promoted self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes (21). The results of these studies are consistent with the results of our study. In fact, educating patients based on their learning style preference is considered an effective way to enhance learning and maximize its retention. Learning style can help people understand their needs and find appropriate learning strategies. Paying attention to learning style also helps educators find the best teaching methods for learners to learn better. Therefore, it seems that a simple intervention such as using the VARK learning style questionnaire before teaching the learner can be effective in promoting their learning. In our study, the use of this educational method led us to the desired learning of the educational content presented. Adherence of patients to what they have learned using this method and its application in daily life led to an acceptable reduction in their blood pressure. Koonce et al. (2011) did not report learning-based education as effective in improving the hypertensive knowledge of patients referred to the emergency department. So that two weeks after their discharge from the emergency center, there was no significant difference in the acquisition of knowledge about hypertension between the experimental and control groups. However, more satisfaction with the training provided was observed among those who were trained based on learning style than the control group whose teaching method was based on printed version (22). Perhaps the reasons for the difference between the results of the mentioned study and the results of the present study are difference in characteristics of the subjects and the type of educational tools used. In addition, the mentioned study was performed on patients admitted to an emergency department, and it seems that the instability of these patients as well as lack of focus on attention may have contributed to the reduced rate of learning during training. In our study, training was conducted on outpatients who are generally stable and better prepared to learn educational materials.

In our study, the mean diastolic blood pressure decreased significantly in all groups after the educational intervention. The mean systolic pressure decreased significant in the visual, aural, and reading/writing but not in the kinesthetic group. Similar to this finding, in a previous study, a training based on the VARK learning style did not significantly change fasting blood sugar of diabetic patients in the kinesthetic group (23). The results of the above study are consistent with the results of our study, so that in our study, education based on learning style was not effective in significantly reducing systolic blood pressure in the kinetic group. Perhaps one of the reasons is the better impact of the teaching method through role-playing and learning on learning practical and manual skills, but the concepts that needed to be understood and taught to patients in the present study did not have such a feature. This inconsistency could be a reason to reduce the effect of the educational method used on the learning rate of patients in this group and consequently the lack of a satisfactory reduction in their systolic blood pressure.

Conclusion

The results showed that training according to learning styles can reduce the systolic and diastolic blood pressures in patients with hypertension. It is recommended to conduct further studies on a larger sample size to confirm the positive effect of this educational method on improving patients' learning. In addition, this study was performed only on patients who had a single-model learning style, while some individuals may have a several learning styles (As in our study, 11 of these individuals were identified and excluded from the study at the time of sampling). Thus, it is recommended to consider this factor when designing future studies.

Acknowledgement

This article had been derived from results of a master's thesis in the field of critical care nursing at Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. We kindly like to thank the Deputy of Research and Technology of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences for financial support and staffs of Bandar Abbas Health Service Centers, staffs of nursing and midwifery faculty, and all participants for their help and cooperation.

Funding source

The study received financial support from the Deputy of Research and Technology of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Ethical statement

Consent was taken from the patients after ensuring confidentiality of personal information. The study has been approved by the ethics committee of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.HUMS.REC.1397.261).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding publication of this article.

What is current knowledge?

Considering the importance of high blood pressure as a cause of ischemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke and kidney dysfunction, it is necessary to implement a self-care program to reduce blood pressure in patients with hypertension.

What is new here?

Self-care training based on VARK learning style preference is effective in lowering blood pressure of patients with high blood pressure.

Introduction

With the rapid social and economic development, lifestyle changes, and aging, high blood pressure has become one of the most important public health issues in the world (1). In 2000, about 972 million people worldwide (around 16%) were living with hypertension, which is anticipated to increase to 4.9 billion people (around 60%) by 2025 (2). Today, the prevalence of this disease has been estimated to be 29.5% in the Eastern Mediterranean region and 22% in Iran (3). The World Health Organization reports that high blood pressure is responsible for 62% of cerebrovascular events and 49% of ischemic heart disease, and causes approximately 7.5 million deaths per year (12.8% of all deaths) worldwide (3,4). Despite the high risk of complications, no much attention has been paid to treatment of hypertension, especially in patients (5). High blood pressure is often asymptomatic, and almost half of the patients are unaware of their disease. The absence of symptoms in the early stages of the disease and the slow onset of complications hiders timely engagement of the patient in the treatment process (either pharmacological or non-pharmacological) (5, 6).

Lack of awareness about high blood pressure is an important challenge in controlling the disease (7). Risk factors for high blood pressure include smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, overweight, sedentary lifestyle, lipid disorders, and high stress. Motivating and educating patients about their illness are the key factors that can be beneficial for them to cope with these risk factors (8). Patient education is a useful tool to improve this knowledge, as it helps patients to improve their lifestyle and promote adherence to medication. Therefore, educational interventions play an important role in the management of hypertension (9). The World Health Organization has recommended patient education as an important strategy to improve patients' active participation in the disease management process (10).

In recent decades, it has been suggested that educators should adapt their teaching style to the specific learner's preference to increase effectiveness of teaching (11). Learning styles refer to the preferred methods of a learner for understanding, absorbing, and interpreting information (12). In fact, learning style is a sensory method by which people prefer to acquire new information (13). People learn to use different strategies to turn an educational message into long-term memory (14). When information is provided using learners' preferred learning styles, educators are better able to communicate with learners, which in turn improves learning (15). Nurses' awareness of learning styles can help them adjust the way of providing educational content in order to strengthen patients' understanding (16). Among the various tools used for determining learners' learning style, the visual, aural, read/write, and kinesthetic (VARK) learning style's questionnaire developed by Neil de Fleming (1987) has good validity and reliability. The results of this questionnaire can help the instructor to choose the most effective method of providing information (14).

Since a limited number of studies have investigated the effect of individual preferred learning style in the field of patient education, this study was conducted to determine effects of self-care training based on the VARK learning style preference on blood pressure of hypertensive patients.

Methods

A semi-experimental study with pretest-posttest design was carried out on 44 patients with hypertension who were referred to six comprehensive health centers in Bandar Abbas (South of Iran) from January to December 2019. Sample size was determined as 40 using the sample size formula to estimate the average of a community taking into account α=0.05, power of 80% (ß=0.20), S=32.5, and d=25 in MedCalc software. Considering the possibility of drop outs, 10% was added to the sample size. After receiving approval from the ethics committee of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.HUMS.REC.1397.261), six health centers in Bandar Abbas (South of Iran) were selected using simple random sampling method. Then, 44 patients with hypertension were selected through convenience sampling method. Informed consent was taken from the participants after explaining the research objectives. Then, based on their learning style preference, the subjects were allocated into four intervention groups including; visual (n=12), aural (n=17), reading/writing (n=8), and kinesthetic (n=7) groups (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria were literacy, no vision or hearing problems, being diagnosed with essential hypertension (stages 1 and 2 hypertension) for at least six months, age of over 18 years, and no learning disability due to mental problems or psychiatric disorders. Data were gathered using a demographic characteristics form (age, sex, level of education, marital status, income level, employment status, smoking, underlying diseases, and drugs/substances) and the VARK learning style questionnaire. A blood pressure monitor and a stethoscope were used to measure blood pressure.

The VARK questionnaire, as a learning preference assessment tool, consists of 16 four-choice questions that can be answered in a short period. All choices correspond to the four sensory modalities including visual, aural, reading/writing, and kinesthetic modes. For each question, the respondents must choose the option that best describes their preferred learning style. If more than one choice matches their preference, they can select more than one option. Depending on the responses, their preferred learning style will be determined (17). In this study, the seventh version of this questionnaire was used, and its reliability was confirmed by obtaining a correlation coefficient of 0.81.

A Richter mercury sphygmomanometer (Diplomat, Germany) and a Richter stethoscope (Germany) were used for measuring blood pressure. Their reliability was confirmed by retest method with a correlation coefficient of 0.93. Blood pressure was measured by a researcher (observing all JNC7 criteria in how to measure blood pressure) from the right hand of patients in sitting position. The subjects were advised to be inactive and not consume heavy food, coffee, and medicine for half an hour before measuring blood pressure. Blood pressure was measured on empty balder after five minutes of rest in a quiet room. To reduce error in measuring blood pressure, calibration was performed by a medical engineer, and blood pressure of all patients in all stages was measured by one person. The trainings were designed and implemented in four, sixty-minute sessions based on the learning style preference of each group (Table 1) (18). The teaching content and methods of education were used according to the learning style of each group (Table 2). To evaluate the effect of educational intervention, the systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured twice, before the intervention and two months after the intervention. Thus, before the first training session, each person's blood pressure was measured and the average of three recent measurements was considered as the baseline (pre-intervention) blood pressure. Two months after the end of the educational interventions, patients' blood pressure was measured four times with an interval of one week between measurements, and the average number of these measurements was recorded as the post-intervention blood pressure

Data were analyzed by using SPSS 16 software. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the frequency of data. One-way analysis of variance was used for intragroup comparison of quantitative variables, and paired t-test and Wilcoxon test were used for comparison of quantitative values (systolic and diastolic blood pressures) before and after the intervention. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Learning style preference of patients is shown in figure 2. The mean age of subjects in the visual, aural, reading/writing, and kinesthetic groups was 60.08±8.71, 58.17±8.59, 52.37±12.59, and 55.57±9.03 years, respectively. The results of one-way analysis of variance showed no significant difference in the mean age of the subjects between the study groups (P=0.329).

Patients in all four groups were homogeneous in terms of other sociodemographic characteristics (Table 3). Most of the patients were married (75%), homemaker (36.4%), with high school education (36.4%) and sufficient income (53%), and no history of opium use (54.5%). The majority of subjects had an underlying disease (86.4%).

According to the results, after the educational intervention, the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures of all patients reduced significantly (Table 4).

The mean systolic blood pressure after the intervention change notably in all groups (P<0.05) except in the kinesthetic group (P>0.05). In addition, a significant difference was observed in the mean diastolic blood pressure of all patients after the intervention compared with baseline (P<0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

The results of the study showed that the VARK learning style training program significantly reduced the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures of patients with hypertension. To our knowledge, this study is the first to employ an educational method based on the VARK learning style in order to reduce blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Similar to our study, Grebner et al. (2015) conducted a pretest-posttest study to investigate the impact of teaching through learning styles on adult health literacy in central Illinois, USA. The results of their study showed the favorable effect of using this educational method in promoting adult health literacy (19). Anbarasi et al. (2014) conducted a pretest-posttest study to investigate the effect of teaching respiratory physiology based on learning style on students' learning in India. The results of their study showed that people who were trained based on their own learning style scored better than those who were trained only via lectures (20). In a study by Saleh Moghadam et al., training-based learning style method promoted self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes (21). The results of these studies are consistent with the results of our study. In fact, educating patients based on their learning style preference is considered an effective way to enhance learning and maximize its retention. Learning style can help people understand their needs and find appropriate learning strategies. Paying attention to learning style also helps educators find the best teaching methods for learners to learn better. Therefore, it seems that a simple intervention such as using the VARK learning style questionnaire before teaching the learner can be effective in promoting their learning. In our study, the use of this educational method led us to the desired learning of the educational content presented. Adherence of patients to what they have learned using this method and its application in daily life led to an acceptable reduction in their blood pressure. Koonce et al. (2011) did not report learning-based education as effective in improving the hypertensive knowledge of patients referred to the emergency department. So that two weeks after their discharge from the emergency center, there was no significant difference in the acquisition of knowledge about hypertension between the experimental and control groups. However, more satisfaction with the training provided was observed among those who were trained based on learning style than the control group whose teaching method was based on printed version (22). Perhaps the reasons for the difference between the results of the mentioned study and the results of the present study are difference in characteristics of the subjects and the type of educational tools used. In addition, the mentioned study was performed on patients admitted to an emergency department, and it seems that the instability of these patients as well as lack of focus on attention may have contributed to the reduced rate of learning during training. In our study, training was conducted on outpatients who are generally stable and better prepared to learn educational materials.

In our study, the mean diastolic blood pressure decreased significantly in all groups after the educational intervention. The mean systolic pressure decreased significant in the visual, aural, and reading/writing but not in the kinesthetic group. Similar to this finding, in a previous study, a training based on the VARK learning style did not significantly change fasting blood sugar of diabetic patients in the kinesthetic group (23). The results of the above study are consistent with the results of our study, so that in our study, education based on learning style was not effective in significantly reducing systolic blood pressure in the kinetic group. Perhaps one of the reasons is the better impact of the teaching method through role-playing and learning on learning practical and manual skills, but the concepts that needed to be understood and taught to patients in the present study did not have such a feature. This inconsistency could be a reason to reduce the effect of the educational method used on the learning rate of patients in this group and consequently the lack of a satisfactory reduction in their systolic blood pressure.

Conclusion

The results showed that training according to learning styles can reduce the systolic and diastolic blood pressures in patients with hypertension. It is recommended to conduct further studies on a larger sample size to confirm the positive effect of this educational method on improving patients' learning. In addition, this study was performed only on patients who had a single-model learning style, while some individuals may have a several learning styles (As in our study, 11 of these individuals were identified and excluded from the study at the time of sampling). Thus, it is recommended to consider this factor when designing future studies.

Acknowledgement

This article had been derived from results of a master's thesis in the field of critical care nursing at Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. We kindly like to thank the Deputy of Research and Technology of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences for financial support and staffs of Bandar Abbas Health Service Centers, staffs of nursing and midwifery faculty, and all participants for their help and cooperation.

Funding source

The study received financial support from the Deputy of Research and Technology of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Ethical statement

Consent was taken from the patients after ensuring confidentiality of personal information. The study has been approved by the ethics committee of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.HUMS.REC.1397.261).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding publication of this article.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: ZGh and EI; Analysis and interpretation of data: ZGh, EI and SHT; Manuscript drafting: ZGh; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: ZGh znd EI; Statistical analysis: ZGh and SHT.

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. 1. Corno L, Hildebrandt N, Voena A. Age of marriage, weather shocks, and the direction of marriage payments. Econometrica. 2020; 88(3):879-915. [DOI:10.3982/ECTA15505]

2. Schweizer V. Marriage: More than a century of change, 1900-2018. Family Profiles, FP-20. 2020; 21. [DOI:10.25035/ncfmr/fp-20-21]

3. Crivello G, Mann G. Young marriage, parenthood and divorce. 2020;

4. Tafere Y, Chuta N, Pankhurst A, Crivello G. Young Marriage, Parenthood and Divorce in Ethiopia. Research Report, Oxford: Young Lives; 2020.

5. Fakhari A, Farahbakhsh M, Azizi H, Esmaeili ED, Mirzapour M, Rahimi VA, et al. Early marriage and negative life events affect on depression in young adults and adolescents. Archives of Iranian medicine. 2020; 23(2):90-8.

6. Darmadi D. Consistency implementation of the regulation on young marriage in Indonesia. Legality: Jurnal Ilmiah Hukum. 2020; 28(2):183-95. [DOI:10.22219/ljih.v28i2.13194]

7. Widyastari DA, Isarabhakdi P, Shaluhiyah Z. Intergenerational patterns of early marriage and childbearing in Rural Central Java, Indonesia. Journal of Population and Social Studies [JPSS]. 2020; 28(3):250-64. [DOI:10.25133/JPSSv28n3.017]

8. Putri FRA. When Girl Become Wives: The Portrait of Underage Marriage in Indonesia. The Indonesian Journal of International Clinical Legal Education. 2020; 2(4):463-80.

9. Statistik BP. Pencegahan Perkawinan Anak percepatan yang tidak bisa ditunda. Badan Pusat Statistik. 2020; 0-44.

10. Choe MK, Thapa S, Achmad SI. Early marriage and childbearing in Indonesia and Nepal. 2001;

11. Laksono AD, Wulandari RD, Matahari R. Does education level matter in women's risk of early marriage?: Case Study in Rural Area in Indonesia. Medico Legal Update. 2021; 21(1):24-8.

12. Hardiani H, Junaidi J. Determinants of early marriage and model of maturing marriage age policy: a case in Jambi Province, Indonesia. Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences. 2018; 11(1):73-92. [DOI:10.12959/issn.1855-0541.IIASS-2018-no1-art5]

13. Susanti E. Women's knowledge and the role of local female leaders in ending the practice of the early marriage of girls in rural communities of Indonesia. Journal of International Women's Studies. 2019; 20(9):3-28.

14. Barkowski S, McLaughlin JS. In sickness and in health: Interaction effects of state and federal health insurance coverage mandates on marriage of young adults. Journal of Human Resources. 2020; [DOI:10.3368/jhr.57.2.0118-9295R2]

15. Dinkes Kota Jambi. Profil Kesehatan Kota Jambi [Internet]. Jambi; 2020. Available from:

16. BPS Provinsi Jambi. Jambi dalam angka [Internet]. 2019. Available from:

17. Uecker JE. Marriage and mental health among young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2012; 53(1):67-83. [DOI:10.1177/0022146511419206] [PMID] [PMCID]

18. Ahmed1&2 S, Khan AKS, Noushad S. Early marriage; a root of current physiological and psychosocial health burdens. 2014. [DOI:10.29052/IJEHSR.v2.i1.2014.50-53]

19. Jensen R, Thornton R. Early female marriage in the developing world. Gender & Development. 2003; 11(2):9-19. [DOI:10.1080/741954311]

20. Kamriani R. Gambaran Pengetahuan Remaja Putri Tentang Risiko Pernikahan Dini Terhadap Kehamilan dan Persalinan di SMA Negeri 1 Sinjai Utara Tahun 2012. Universitas Islam Negeri Alauddin Makassar; 2012.

21. Novitasari V, Yorita E, Andeka W, Andriani L, Hartini LH. Kajian Faktor Risiko Pernikahan Dini pada Perempuan di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Kembang Seri Kecamatan Talang Empat Kabupaten Bengkulu Tengah Tahun 2018. Poltekkes Kemenkes Bengkulu; 2018.

22. Sharif I, Wills TA, Sargent JD. Effect of visual media use on school performance: a prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010; 46(1):52-61. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.05.012] [PMID] [PMCID]

23. Novitasari E. Layanan Informasi dengan Media Audiovisual untuk Meningkatkan Pemahaman tentang Motif Menikah dikalangan Siswa. Indonesian Journal of Guidance and Counseling: Theory and Application. 2019; 8(2):108-13. [DOI:10.15294/ijgc.v8i2.22387]

24. Notoatmodjo S. Ilmu Perilaku Kesehatan. Jakarta. Jakarta: Jakarta. CV. Rineka Cipta. Hal. 177-179; 2014. Jakarta.

25. Putri BDY, Herinawati H, Susilawati E. Pengaruh Promosi Kesehatan Tentang Bounding Attachment Berbasis Video Animasi Terhadap Pengetahuan Ibu Hamil. Nursing Care and Health Technology Journal (NCHAT). 2021; 1(3):155-61.

26. Birang, R K, Y, Yazdapanah F NM. The effect of education by visual media on oral health promotion of students. Arak Medical Unicersity Journal (AMUJ). 2006; 9(Supp (Summer)):1-6.

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |