Volume 22, Issue 2 (6-2025)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025, 22(2): 17-22 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Motie M, Fallahi-khoshknab M, Mohammadi Shahbolaghi F, Khanjani M S, Stueck M, Khankeh H. Secondary traumatic stress in emergency department nurses: A multi-methods study protocol. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025; 22 (2) :17-22

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1990-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1990-en.html

Mahdieh Motie1

, Masoud Fallahi-khoshknab1

, Masoud Fallahi-khoshknab1

, Farahnaz Mohammadi Shahbolaghi2

, Farahnaz Mohammadi Shahbolaghi2

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani3

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani3

, Marcus Stueck4

, Marcus Stueck4

, Hamidreza Khankeh *5

, Hamidreza Khankeh *5

, Masoud Fallahi-khoshknab1

, Masoud Fallahi-khoshknab1

, Farahnaz Mohammadi Shahbolaghi2

, Farahnaz Mohammadi Shahbolaghi2

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani3

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani3

, Marcus Stueck4

, Marcus Stueck4

, Hamidreza Khankeh *5

, Hamidreza Khankeh *5

1- Department of Nursing, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- International Biocentric Research Academy (IBRA), Leipzig, Germany

5- Health in Emergency and Disaster Research Center, Social Health Research Institute, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran ; QUEST Center for Responsible Research, Berlin Institute of Health at Charité, Berlin, Germany ,hrkhankeh@gmail.com

2- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- International Biocentric Research Academy (IBRA), Leipzig, Germany

5- Health in Emergency and Disaster Research Center, Social Health Research Institute, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran ; QUEST Center for Responsible Research, Berlin Institute of Health at Charité, Berlin, Germany ,

Keywords: Compassion Fatigue, Secondary Traumatic Stress, Secondary Traumatization, Vicarious Trauma, Emergency Nursing

Full-Text [PDF 464 kb]

(364 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1075 Views)

Grounded theory is a powerful methodology for explaining complex social processes. This methodology allows researchers to derive a substantive theory from qualitative data obtained from interviews, observations, and other sources. In this study, this methodology will be applied to explain the process of STS in emergency nurses. A grounded theory qualitative research methodology recommended by Corbin and Strauss (2015) will be used (24).

Participants

The main participants of this study are a number of nurses working in the emergency departments of hospitals in Tehran and Qazvin (Iran). Moreover, in this study, based on the findings and theoretical sampling with other health providers, patients, and their families, the nurses' families will be asked to participate to further enrich the study.

Sampling

In this study, two sampling methods will be used: purposive sampling followed by theoretical sampling (25,26).

Participants should have experience or knowledge of STS and be willing to participate. There is no age limitation, but they must be able to articulate their experiences and opinions. Specific conditions, such as mental illnesses or health problems, may prevent participation, and individuals with these conditions will be excluded. In qualitative research, the sample size is determined based on the level of conceptual saturation. This means that sampling continues until the data can no longer provide new codes and concepts regarding the phenomenon under study. Data saturation occurs when new data becomes repetitive, and no additional insights can be added to the analysis. This stage indicates that researchers have achieved a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of STS and can cease the sampling process.

Data collection

In-depth individual interviews will be used, and if necessary, observations of interactions and relationships between nurses and patients and their families will also be conducted to explore the experiences and perceptions of study participants regarding STS (26).

Examples of questions considered in an interview with nurses

The emergency department is a place where you care for patients who have suddenly suffered an injury. Could you tell me about your experience in caring for these patients? How do you feel when working with an injured patient? Could you describe your feelings? Is there anything else you would like to share?

Data analysis

This qualitative approach consists of five main stages of data analysis: 1- open coding to identify concepts, 2- developing concepts according to their properties and dimensions, 3- analyzing data for context, 4- bringing the process into the analysis, and 5- integrating categories (24). The five main stages are as follows:

Open coding – Identifying concepts:

In this initial stage, the researcher conducts a detailed, line-by-line analysis of the data, assigning conceptual labels (Codes) to meaningful units of text. Through constant comparison, similarities and differences among codes are identified, leading to the grouping of related codes into preliminary categories and subcategories as high-level concepts (24).

Development of concepts based on properties and dimensions:

At this stage, the researcher refines the identified concepts by analyzing their defining properties and dimensions (24).

Contextualizing the data:

The researcher explores how categories and subcategories are influenced by specific conditions, situations, or events. By exploring the context in which phenomena occur, this stage helps explain the relationships between developed concepts and the broader social or situational factors affecting them (24).

Incorporating process into analysis:

This stage focuses on understanding actions, interactions, and emotional responses related to the identified concepts. The researcher explores how emergency nurses engage with the phenomenon over time, capturing changes, adaptations, and dynamic developments in response to evolving conditions (24).

Integration and theoretical development:

In the final stage, the researcher integrates the developed concepts around a central theme or core category, which represents the primary process or phenomenon under study. By establishing connections between concepts and validating their coherence, the researcher ensures theoretical saturation and strengthens the explanatory power of the emerging theory (24).

Throughout the analysis, key grounded theory strategies-such as constant comparison, theoretical comparison, theoretical sampling, and memo writing-are employed to refine concepts, enhance theoretical sensitivity, and develop a robust, well-grounded theory (24).

Data trustworthiness

According to the grounded theory method by Corbin (2015), ten main factors will be utilized: fit, applicability, concepts, contextualization of concepts, logic, depth, variation, creativity, sensitivity, and evidence of memos (24).

Scoping review

In the second stage, our goal is to examine challenges and barriers in managing STS in nurses working in the emergency department based on national and international experiences. In this stage, according to the findings of the first part of the study, the structural factors affecting the process will be identified. Based on the extracted concepts, a scoping review will be conducted using the five-step approach of Arksey and O’Malley as well as the developed PRISMA reporting model (27). This process is carried out in order to extract the written experiences of nurses from the integration of the study findings, identified challenges, and solutions.

Identifying research questions

In this step, we will seek to answer the questions, "How do nurses react to STS and what strategies do they use to manage it?" and "What are the main challenges nurses face in managing STS and how do they affect their performance?"

Identifying relevant studies

The selection of keywords for searching electronic databases will involve reviewing relevant literature and considering Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or subject heading search terms related to key concepts. Following the completion of Phase 1 of the study, a comprehensive literature search will be conducted to identify relevant studies that align with the objectives of this scoping review. The search will be performed systematically across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), and Web of Science. The search strategy will include synonyms and closely related terms for both “STS” and “emergency nurses” to enhance sensitivity. In the second stage of the scoping review, the process will be based on the results of the first stage. For this reason, it is not possible to write a search strategy for the syntax from the beginning. In fact, the syntax will be developed after the second stage, influenced by the results of the first stage.

Selecting studies

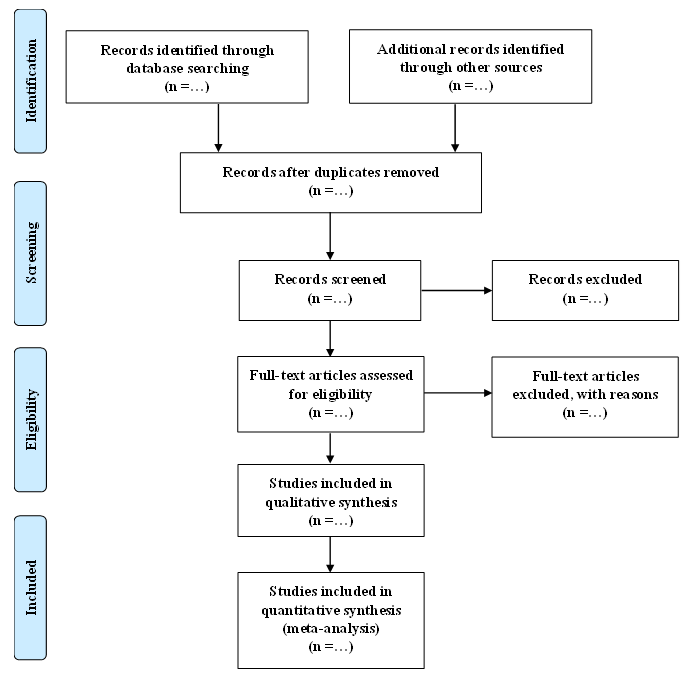

The selection of studies will take place in two phases of screening. First, two researchers (MM and HK) will independently evaluate the titles and abstracts of articles to identify relevant studies. In the second phase, studies that fulfill the inclusion criteria will be selected for the final report. The inclusion criteria will encompass all pertinent studies published in English that have accessible full texts and no time limit. The results of the screening will be illustrated using a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2).

Full-Text: (158 Views)

Introduction

Secondary traumatic stress (STS) refers to a state in which people suffer psychological and emotional complications due to being exposed to the traumatic experiences of others (1). STS results from work-related secondary exposure to highly stressful events (2,3). This type of stress is especially common in healthcare-related professions, such as emergency department nurses (4). These nurses frequently encounter patients and their families who are in critical and traumatic situations (5,6). The nature of emergency care is characterized by rapid decision-making, high-stakes scenarios, and the potential for witnessing severe injuries and loss, which place nurses at significant risk for developing STS (7,8).

Emergency department nurses operate in one of the most high-stress environments within the healthcare system, where they are frequently exposed to traumatic events and the suffering of patients (7,9). This relentless exposure can lead to a phenomenon known as STS, which arises from the emotional toll of witnessing the trauma and distress experienced by others (5). Unlike traditional forms of trauma, STS does not stem from direct exposure to a traumatic event but rather from empathetic engagement with patients and their families during critical and often life-threatening situations (10,11). For instance, nearly 30.7% of individuals assessed were found to be at moderate risk of experiencing STS based on the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (11). Furthermore, various qualitative studies have examined the emotional struggles and ethical dilemmas encountered by nurses caring for trauma patients, emphasizing the enduring effects of STS on both psychological well-being and the standard of patient care (5,12).

Symptoms may include anxiety, depression, emotional numbness, and a decreased sense of personal accomplishment, which can adversely affect both their professional performance and personal well-being (13,14). The cumulative effect of these stressors not only impacts the nurses themselves but also has broader implications for patient care, staff retention, and overall healthcare outcomes (4,15,16).

Given the importance of the effects of STS on nurses, especially nurses working in emergency departments, and the subsequent impact on the care provided to patients, as well as the prevention of its effects and the lack of studies in this field, there is a need to conduct comprehensive studies in this field (17,18).

This type of stress is caused by repeated contact with people who have experienced trauma themselves and hearing their stories or seeing the effects of trauma on them (14,19,20). For example, a nurse who repeatedly hears or encounters stories about traumatic events that happen to patients, or a person who is exposed to the traumatic events of others, such as working in a hospital emergency department, is experiencing secondary exposure (20).

In recent decades, there has been an increasing focus on STS, which remains relatively nascent (21). Most studies have primarily addressed its quantitative dimensions (22,23), while its subjective aspects, which need to be investigated using a qualitative paradigm, have received less attention. To date, no in-depth qualitative study employing a grounded theory approach has been conducted to explore this concept within the context of Iran. We will conduct this study to deeply explore the phenomenon of STS and compile a policy brief. This study protocol outlines a step-by-step guide for conducting a multi-methods study, addressing related challenges, and exploring STS. It emphasizes research integrity, ethical considerations, and methodological rigor. The authors advocate for publishing multi-methods protocols in advance to enhance research quality, support ethical practices, and assist novice researchers.

Methods

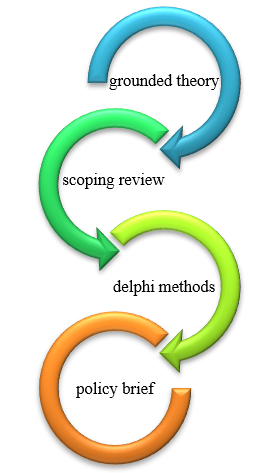

This study will be a multi-method approach through qualitative research, combining three sub-studies, including grounded theory, a literature review, and the Delphi method, and will culminate in the compilation of a policy brief (Figure 1).

Secondary traumatic stress (STS) refers to a state in which people suffer psychological and emotional complications due to being exposed to the traumatic experiences of others (1). STS results from work-related secondary exposure to highly stressful events (2,3). This type of stress is especially common in healthcare-related professions, such as emergency department nurses (4). These nurses frequently encounter patients and their families who are in critical and traumatic situations (5,6). The nature of emergency care is characterized by rapid decision-making, high-stakes scenarios, and the potential for witnessing severe injuries and loss, which place nurses at significant risk for developing STS (7,8).

Emergency department nurses operate in one of the most high-stress environments within the healthcare system, where they are frequently exposed to traumatic events and the suffering of patients (7,9). This relentless exposure can lead to a phenomenon known as STS, which arises from the emotional toll of witnessing the trauma and distress experienced by others (5). Unlike traditional forms of trauma, STS does not stem from direct exposure to a traumatic event but rather from empathetic engagement with patients and their families during critical and often life-threatening situations (10,11). For instance, nearly 30.7% of individuals assessed were found to be at moderate risk of experiencing STS based on the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (11). Furthermore, various qualitative studies have examined the emotional struggles and ethical dilemmas encountered by nurses caring for trauma patients, emphasizing the enduring effects of STS on both psychological well-being and the standard of patient care (5,12).

Symptoms may include anxiety, depression, emotional numbness, and a decreased sense of personal accomplishment, which can adversely affect both their professional performance and personal well-being (13,14). The cumulative effect of these stressors not only impacts the nurses themselves but also has broader implications for patient care, staff retention, and overall healthcare outcomes (4,15,16).

Given the importance of the effects of STS on nurses, especially nurses working in emergency departments, and the subsequent impact on the care provided to patients, as well as the prevention of its effects and the lack of studies in this field, there is a need to conduct comprehensive studies in this field (17,18).

This type of stress is caused by repeated contact with people who have experienced trauma themselves and hearing their stories or seeing the effects of trauma on them (14,19,20). For example, a nurse who repeatedly hears or encounters stories about traumatic events that happen to patients, or a person who is exposed to the traumatic events of others, such as working in a hospital emergency department, is experiencing secondary exposure (20).

In recent decades, there has been an increasing focus on STS, which remains relatively nascent (21). Most studies have primarily addressed its quantitative dimensions (22,23), while its subjective aspects, which need to be investigated using a qualitative paradigm, have received less attention. To date, no in-depth qualitative study employing a grounded theory approach has been conducted to explore this concept within the context of Iran. We will conduct this study to deeply explore the phenomenon of STS and compile a policy brief. This study protocol outlines a step-by-step guide for conducting a multi-methods study, addressing related challenges, and exploring STS. It emphasizes research integrity, ethical considerations, and methodological rigor. The authors advocate for publishing multi-methods protocols in advance to enhance research quality, support ethical practices, and assist novice researchers.

Methods

This study will be a multi-method approach through qualitative research, combining three sub-studies, including grounded theory, a literature review, and the Delphi method, and will culminate in the compilation of a policy brief (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Implementation steps |

Grounded theory is a powerful methodology for explaining complex social processes. This methodology allows researchers to derive a substantive theory from qualitative data obtained from interviews, observations, and other sources. In this study, this methodology will be applied to explain the process of STS in emergency nurses. A grounded theory qualitative research methodology recommended by Corbin and Strauss (2015) will be used (24).

Participants

The main participants of this study are a number of nurses working in the emergency departments of hospitals in Tehran and Qazvin (Iran). Moreover, in this study, based on the findings and theoretical sampling with other health providers, patients, and their families, the nurses' families will be asked to participate to further enrich the study.

Sampling

In this study, two sampling methods will be used: purposive sampling followed by theoretical sampling (25,26).

Participants should have experience or knowledge of STS and be willing to participate. There is no age limitation, but they must be able to articulate their experiences and opinions. Specific conditions, such as mental illnesses or health problems, may prevent participation, and individuals with these conditions will be excluded. In qualitative research, the sample size is determined based on the level of conceptual saturation. This means that sampling continues until the data can no longer provide new codes and concepts regarding the phenomenon under study. Data saturation occurs when new data becomes repetitive, and no additional insights can be added to the analysis. This stage indicates that researchers have achieved a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of STS and can cease the sampling process.

Data collection

In-depth individual interviews will be used, and if necessary, observations of interactions and relationships between nurses and patients and their families will also be conducted to explore the experiences and perceptions of study participants regarding STS (26).

Examples of questions considered in an interview with nurses

The emergency department is a place where you care for patients who have suddenly suffered an injury. Could you tell me about your experience in caring for these patients? How do you feel when working with an injured patient? Could you describe your feelings? Is there anything else you would like to share?

Data analysis

This qualitative approach consists of five main stages of data analysis: 1- open coding to identify concepts, 2- developing concepts according to their properties and dimensions, 3- analyzing data for context, 4- bringing the process into the analysis, and 5- integrating categories (24). The five main stages are as follows:

Open coding – Identifying concepts:

In this initial stage, the researcher conducts a detailed, line-by-line analysis of the data, assigning conceptual labels (Codes) to meaningful units of text. Through constant comparison, similarities and differences among codes are identified, leading to the grouping of related codes into preliminary categories and subcategories as high-level concepts (24).

Development of concepts based on properties and dimensions:

At this stage, the researcher refines the identified concepts by analyzing their defining properties and dimensions (24).

Contextualizing the data:

The researcher explores how categories and subcategories are influenced by specific conditions, situations, or events. By exploring the context in which phenomena occur, this stage helps explain the relationships between developed concepts and the broader social or situational factors affecting them (24).

Incorporating process into analysis:

This stage focuses on understanding actions, interactions, and emotional responses related to the identified concepts. The researcher explores how emergency nurses engage with the phenomenon over time, capturing changes, adaptations, and dynamic developments in response to evolving conditions (24).

Integration and theoretical development:

In the final stage, the researcher integrates the developed concepts around a central theme or core category, which represents the primary process or phenomenon under study. By establishing connections between concepts and validating their coherence, the researcher ensures theoretical saturation and strengthens the explanatory power of the emerging theory (24).

Throughout the analysis, key grounded theory strategies-such as constant comparison, theoretical comparison, theoretical sampling, and memo writing-are employed to refine concepts, enhance theoretical sensitivity, and develop a robust, well-grounded theory (24).

Data trustworthiness

According to the grounded theory method by Corbin (2015), ten main factors will be utilized: fit, applicability, concepts, contextualization of concepts, logic, depth, variation, creativity, sensitivity, and evidence of memos (24).

Scoping review

In the second stage, our goal is to examine challenges and barriers in managing STS in nurses working in the emergency department based on national and international experiences. In this stage, according to the findings of the first part of the study, the structural factors affecting the process will be identified. Based on the extracted concepts, a scoping review will be conducted using the five-step approach of Arksey and O’Malley as well as the developed PRISMA reporting model (27). This process is carried out in order to extract the written experiences of nurses from the integration of the study findings, identified challenges, and solutions.

Identifying research questions

In this step, we will seek to answer the questions, "How do nurses react to STS and what strategies do they use to manage it?" and "What are the main challenges nurses face in managing STS and how do they affect their performance?"

Identifying relevant studies

The selection of keywords for searching electronic databases will involve reviewing relevant literature and considering Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or subject heading search terms related to key concepts. Following the completion of Phase 1 of the study, a comprehensive literature search will be conducted to identify relevant studies that align with the objectives of this scoping review. The search will be performed systematically across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), and Web of Science. The search strategy will include synonyms and closely related terms for both “STS” and “emergency nurses” to enhance sensitivity. In the second stage of the scoping review, the process will be based on the results of the first stage. For this reason, it is not possible to write a search strategy for the syntax from the beginning. In fact, the syntax will be developed after the second stage, influenced by the results of the first stage.

Selecting studies

The selection of studies will take place in two phases of screening. First, two researchers (MM and HK) will independently evaluate the titles and abstracts of articles to identify relevant studies. In the second phase, studies that fulfill the inclusion criteria will be selected for the final report. The inclusion criteria will encompass all pertinent studies published in English that have accessible full texts and no time limit. The results of the screening will be illustrated using a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2).

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram |

Charting the data and sorting information

The data charting process will be tailored to align with the objectives of the study and will specifically address the primary research questions. A data extraction table will be constructed with input from the research team and refined through a review of multiple relevant articles before the commencement of the actual data extraction. This table contains important information about each study, which includes authors, year of publication, research objective, methodology, and results. In the study results section, we will seek to identify and categorize key information. At this stage, the focus will be on extracting data such as the prevalence and incidence of STS, effective and risk factors in the occurrence of this phenomenon, psychological, emotional, and occupational consequences resulting from it, individual or organizational interventions, and strategies offered to prevent or reduce the effects of STS. This stage will be completed by a researcher (MM) and approved by all team members. The findings will be compared and synthesized to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

This data will be organized into a structured data extraction table and categorized into thematic topics based on identified commonalities, facilitating a logical structuring of the findings. The summarization of findings will include providing a descriptive overview that highlights major themes, trends, and gaps in the literature, encapsulating the breadth of the research landscape without detailed analysis. Visual representations, such :as char:ts, tables, and graphs, will be utilized to present the data clearly, helping readers easily comprehend complex information.

For reporting results, findings will be presented in a structured format, often adhering to guidelines like PRISMA-ScR to ensure clarity and consistency. The implications of the findings for future research, policy, and practice will be discussed, emphasizing the contribution of the scoping review to the field and identifying areas for further investigation. Additionally, any limitations encountered during the review process, such as potential biases in study selection or data extraction, will be acknowledged, along with their possible impact on the findings.

Delphi methods

The results of the first stage, which are extracted in the form of grounded theory concepts, facilitators and barriers, structural factors, and the opinions of the research team, and the results of the literature review stage, which include recommendations and facilitators, will be integrated. Moreover, the overall results for consensus will be extracted in the form of the classic Delphi method and an expert panel, which will be a group of nurses and experts who will be selected and invited to discuss and exchange opinions in multiple Delphi sessions. These people can share their experiences and perspectives on STS in emergency nurses. With this method, we can collect different perspectives and conduct a deeper analysis of STS in nurses (28,29).

The Delphi method aims to achieve a consensus among experts on a specific topic-in this case, STS in emergency nurses. By utilizing multiple rounds of questionnaires, the method facilitates the collection of diverse perspectives, fosters discussion, and helps refine ideas and recommendations based on expert feedback. This iterative process allows for the emergence of well-rounded insights and strategies to address the challenges faced by nurses experiencing STS.

The participants in this Delphi study will include:

Nurses: Specifically, emergency nurses who have firsthand experience with STS. Their insights will be invaluable in understanding the practical implications of this phenomenon in their daily work.

Experts: Professionals with expertise in trauma, mental health, nursing, and emergency care. These experts can provide a broader perspective on the issue and contribute evidence-based recommendations for addressing STS.

Participants will be selected based on their experience, knowledge, and ability to provide valuable insights into the subject matter. They will be invited to engage in multiple Delphi sessions to discuss and share their perspectives.

The Delphi study will include approximately 15 to 20 participants, comprising emergency nurses and experts in trauma, mental health, nursing, and emergency care. This sample size is considered appropriate for achieving diverse perspectives while maintaining manageable consensus-building throughout the rounds (28-30).

Questions for the Delphi sessions:

The questions posed during the Delphi sessions will be designed based on the results of the first two phases of the study to elicit comprehensive feedback and facilitate discussion among participants. By focusing on explored areas, the Delphi method will enable the research team to gather diverse insights, promote dialogue among participants, and ultimately arrive at a consensus on best practices for addressing STS in emergency nurses.

Policy brief

A policy brief is also a short document that prioritizes a specific policy issue and presents evidence in plain language that is understandable to everyone. These documents are usually designed to present key information and practical recommendations concisely and clearly. Since decision-makers at both the micro and macro levels need concise and complete information, and policymakers are usually busy people and do not have sufficient expertise in all areas, it is interesting and helpful for them to receive concise but important information for decision-making and to provide solutions (31-35). These summaries should be able to present key insights and practical recommendations in the shortest possible time in an organized and understandable manner. For example, when faced with an issue such as STS in emergency nurses, a policy brief could include information on the prevalence of this problem, risk factors, its effects on the quality of work and the health of nurses, as well as suggestions for reducing this stress. In addition, an effective policy brief should present valid and up-to-date evidence and help its audience quickly understand the advantages and disadvantages of different options. The document should also be attractive in terms of design and appearance to attract the audience's attention and encourage them to read it. The use of charts, tables, and highlights can help better and faster understand the content. These types of documents act as a powerful tool to facilitate communication between researchers and policymakers and play an important role in translating scientific knowledge into practical and effective actions (34,36).

After collecting information from the first and second stages and holding an expert panel, a policy brief will be compiled including different parts (34):

Title: The Issue Under Discussion for Presenting the Policy Brief

Problem statement: Describe the problem and highlight the importance of addressing it at both national and international levels.

Relevant scientific literature: Summarize existing studies in the field and outline current challenges.

Main body of the report: Present the findings of the current research along with a critical analysis.

Policy solutions: Provide actionable policy recommendations.

Stakeholders: Health policymakers, managers, and nurses.

Limitations and Strengths

One of the limitations of this study could be the crowded emergency department environment for data collection. We will conduct our qualitative interviews in a private room at the end of the emergency department where we could close the room and make the environment quiet. One of the strengths of this study is the first author's experience working in the emergency department, which increases the theoretical sensitivity of the study. Another strength of this study is that the research team consists of prominent researchers in qualitative research from Iran and Germany.

Conclusion

This study protocol outlines the steps for conducting a multi-methods study aimed at deeply exploring the phenomenon of STS and compiling a policy brief. The detailed, step-by-step description of the research process is intended to guide researchers in conducting studies using similar methodologies. The protocol addresses common limitations faced by researchers working in different languages and discusses solutions to overcome these challenges. Efforts have been made to ensure the integrity of the study, providing criteria that researchers can follow to conduct high-quality studies. Ethical considerations have been meticulously addressed and discussed in detail by the authors. The researchers believe that publishing this multi-methods research protocol before implementation can pave the way for improved research integrity, foster integrated and ethical research practices, and serve as a valuable guide for novice researchers.

Given that the phenomenon of STS is highly complex and has different dimensions, nurses working in emergency departments are frequently exposed to it. Conducting comprehensive multi-method studies is highly recommended. The results of this study will reduce the psychological and physical harm of STS in emergency nurses and will also increase job satisfaction and service to patients. Health policymakers should use the results of this study as a roadmap.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences for its support, without which this study would not have been possible.

Funding sources

This project is the first author's thesis and has received no financial support.

Ethical statement

The researchers will ensure that participants are thoroughly informed about the research process and will obtain their informed consent. Interviews will be conducted with the participants’ awareness and consent, guaranteeing the confidentiality of all personal information. The researchers are dedicated to disseminating the study’s findings in a way that serves the interests of stakeholders. Additionally, this study has been reviewed by the USWR Ethics Committee and has received the ethics approval code IR.USWR.REC.1403.209.

For secondary analyses utilizing existing data, it will be specified that the original consent obtained will cover secondary analysis without the need for additional consent from participants.

All data collected during the study will be anonymized to ensure participant privacy. Identifiable information will be removed, and unique identifiers will be assigned to maintain confidentiality. If any identifiable data is collected, protective measures will include secure storage and restricted access to safeguard participant information. Participants in this study will receive a gift for their participation. This compensation will be provided to ensure fairness and transparency in the research process.

No identifiable images of participants will be included in the manuscript or supplementary materials. In the event that such images are unavoidable, it will be confirmed that consent has been granted by identifiable individuals for their use. Relevant consent forms and written communications will be uploaded in the “Other files” field during resubmission. By addressing these ethical considerations, this research will adhere to the highest standards of integrity and respect for the participants’ rights and welfare.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

MM and HK contributed to conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, and editing. MM and HK will handle data curation. HK, MF, FM, MK, and MS performed project administration. MM and HK handled supervision, writing–review, and editing.

Data availability statement

This article is a protocol and does not include any data.

The data charting process will be tailored to align with the objectives of the study and will specifically address the primary research questions. A data extraction table will be constructed with input from the research team and refined through a review of multiple relevant articles before the commencement of the actual data extraction. This table contains important information about each study, which includes authors, year of publication, research objective, methodology, and results. In the study results section, we will seek to identify and categorize key information. At this stage, the focus will be on extracting data such as the prevalence and incidence of STS, effective and risk factors in the occurrence of this phenomenon, psychological, emotional, and occupational consequences resulting from it, individual or organizational interventions, and strategies offered to prevent or reduce the effects of STS. This stage will be completed by a researcher (MM) and approved by all team members. The findings will be compared and synthesized to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

This data will be organized into a structured data extraction table and categorized into thematic topics based on identified commonalities, facilitating a logical structuring of the findings. The summarization of findings will include providing a descriptive overview that highlights major themes, trends, and gaps in the literature, encapsulating the breadth of the research landscape without detailed analysis. Visual representations, such :as char:ts, tables, and graphs, will be utilized to present the data clearly, helping readers easily comprehend complex information.

For reporting results, findings will be presented in a structured format, often adhering to guidelines like PRISMA-ScR to ensure clarity and consistency. The implications of the findings for future research, policy, and practice will be discussed, emphasizing the contribution of the scoping review to the field and identifying areas for further investigation. Additionally, any limitations encountered during the review process, such as potential biases in study selection or data extraction, will be acknowledged, along with their possible impact on the findings.

Delphi methods

The results of the first stage, which are extracted in the form of grounded theory concepts, facilitators and barriers, structural factors, and the opinions of the research team, and the results of the literature review stage, which include recommendations and facilitators, will be integrated. Moreover, the overall results for consensus will be extracted in the form of the classic Delphi method and an expert panel, which will be a group of nurses and experts who will be selected and invited to discuss and exchange opinions in multiple Delphi sessions. These people can share their experiences and perspectives on STS in emergency nurses. With this method, we can collect different perspectives and conduct a deeper analysis of STS in nurses (28,29).

The Delphi method aims to achieve a consensus among experts on a specific topic-in this case, STS in emergency nurses. By utilizing multiple rounds of questionnaires, the method facilitates the collection of diverse perspectives, fosters discussion, and helps refine ideas and recommendations based on expert feedback. This iterative process allows for the emergence of well-rounded insights and strategies to address the challenges faced by nurses experiencing STS.

The participants in this Delphi study will include:

Nurses: Specifically, emergency nurses who have firsthand experience with STS. Their insights will be invaluable in understanding the practical implications of this phenomenon in their daily work.

Experts: Professionals with expertise in trauma, mental health, nursing, and emergency care. These experts can provide a broader perspective on the issue and contribute evidence-based recommendations for addressing STS.

Participants will be selected based on their experience, knowledge, and ability to provide valuable insights into the subject matter. They will be invited to engage in multiple Delphi sessions to discuss and share their perspectives.

The Delphi study will include approximately 15 to 20 participants, comprising emergency nurses and experts in trauma, mental health, nursing, and emergency care. This sample size is considered appropriate for achieving diverse perspectives while maintaining manageable consensus-building throughout the rounds (28-30).

Questions for the Delphi sessions:

The questions posed during the Delphi sessions will be designed based on the results of the first two phases of the study to elicit comprehensive feedback and facilitate discussion among participants. By focusing on explored areas, the Delphi method will enable the research team to gather diverse insights, promote dialogue among participants, and ultimately arrive at a consensus on best practices for addressing STS in emergency nurses.

Policy brief

A policy brief is also a short document that prioritizes a specific policy issue and presents evidence in plain language that is understandable to everyone. These documents are usually designed to present key information and practical recommendations concisely and clearly. Since decision-makers at both the micro and macro levels need concise and complete information, and policymakers are usually busy people and do not have sufficient expertise in all areas, it is interesting and helpful for them to receive concise but important information for decision-making and to provide solutions (31-35). These summaries should be able to present key insights and practical recommendations in the shortest possible time in an organized and understandable manner. For example, when faced with an issue such as STS in emergency nurses, a policy brief could include information on the prevalence of this problem, risk factors, its effects on the quality of work and the health of nurses, as well as suggestions for reducing this stress. In addition, an effective policy brief should present valid and up-to-date evidence and help its audience quickly understand the advantages and disadvantages of different options. The document should also be attractive in terms of design and appearance to attract the audience's attention and encourage them to read it. The use of charts, tables, and highlights can help better and faster understand the content. These types of documents act as a powerful tool to facilitate communication between researchers and policymakers and play an important role in translating scientific knowledge into practical and effective actions (34,36).

After collecting information from the first and second stages and holding an expert panel, a policy brief will be compiled including different parts (34):

Title: The Issue Under Discussion for Presenting the Policy Brief

Problem statement: Describe the problem and highlight the importance of addressing it at both national and international levels.

Relevant scientific literature: Summarize existing studies in the field and outline current challenges.

Main body of the report: Present the findings of the current research along with a critical analysis.

Policy solutions: Provide actionable policy recommendations.

Stakeholders: Health policymakers, managers, and nurses.

Limitations and Strengths

One of the limitations of this study could be the crowded emergency department environment for data collection. We will conduct our qualitative interviews in a private room at the end of the emergency department where we could close the room and make the environment quiet. One of the strengths of this study is the first author's experience working in the emergency department, which increases the theoretical sensitivity of the study. Another strength of this study is that the research team consists of prominent researchers in qualitative research from Iran and Germany.

Conclusion

This study protocol outlines the steps for conducting a multi-methods study aimed at deeply exploring the phenomenon of STS and compiling a policy brief. The detailed, step-by-step description of the research process is intended to guide researchers in conducting studies using similar methodologies. The protocol addresses common limitations faced by researchers working in different languages and discusses solutions to overcome these challenges. Efforts have been made to ensure the integrity of the study, providing criteria that researchers can follow to conduct high-quality studies. Ethical considerations have been meticulously addressed and discussed in detail by the authors. The researchers believe that publishing this multi-methods research protocol before implementation can pave the way for improved research integrity, foster integrated and ethical research practices, and serve as a valuable guide for novice researchers.

Given that the phenomenon of STS is highly complex and has different dimensions, nurses working in emergency departments are frequently exposed to it. Conducting comprehensive multi-method studies is highly recommended. The results of this study will reduce the psychological and physical harm of STS in emergency nurses and will also increase job satisfaction and service to patients. Health policymakers should use the results of this study as a roadmap.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences for its support, without which this study would not have been possible.

Funding sources

This project is the first author's thesis and has received no financial support.

Ethical statement

The researchers will ensure that participants are thoroughly informed about the research process and will obtain their informed consent. Interviews will be conducted with the participants’ awareness and consent, guaranteeing the confidentiality of all personal information. The researchers are dedicated to disseminating the study’s findings in a way that serves the interests of stakeholders. Additionally, this study has been reviewed by the USWR Ethics Committee and has received the ethics approval code IR.USWR.REC.1403.209.

For secondary analyses utilizing existing data, it will be specified that the original consent obtained will cover secondary analysis without the need for additional consent from participants.

All data collected during the study will be anonymized to ensure participant privacy. Identifiable information will be removed, and unique identifiers will be assigned to maintain confidentiality. If any identifiable data is collected, protective measures will include secure storage and restricted access to safeguard participant information. Participants in this study will receive a gift for their participation. This compensation will be provided to ensure fairness and transparency in the research process.

No identifiable images of participants will be included in the manuscript or supplementary materials. In the event that such images are unavoidable, it will be confirmed that consent has been granted by identifiable individuals for their use. Relevant consent forms and written communications will be uploaded in the “Other files” field during resubmission. By addressing these ethical considerations, this research will adhere to the highest standards of integrity and respect for the participants’ rights and welfare.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

MM and HK contributed to conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, and editing. MM and HK will handle data curation. HK, MF, FM, MK, and MS performed project administration. MM and HK handled supervision, writing–review, and editing.

Data availability statement

This article is a protocol and does not include any data.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. Park H, Kim H, Kim H. A Scoping Review of Secondary Traumatic Stress in Nurses Working in the Emergency Department or Trauma Care Settings. J Adv Nurs. 2025. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Xu Z, Zhao B, Zhang Z, Wang X, Jiang Y, Zhang M, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of secondary traumatic stress in emergency nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2024;15(1):2321761. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Badr S, Nyce A, Awan T, Cortes D, Mowdawalla C, Rachoin J-S. Measures of emergency department crowding, a systematic review. how to make sense of a long list. Open Access Emerg Med. 2022;14:5-14. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Barleycorn D. Awareness of secondary traumatic stress in emergency nursing. Emerg Nurse. 2019;27(5):19-22. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Alshammari B, Alanazi NF, Kreedi F, Alshammari F, Alkubati SA, Alrasheeday A, et al. Exposure to secondary traumatic stress and its related factors among emergency nurses in Saudi Arabia: a mixed method study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):337. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Zhang H, Xia Z, Yu S, Shi H, Meng Y, Dator WL. Interventions for Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress in Nurses: A Systematic Review and Network Meta‐Analysis.Nurs Health Sci. 2025;27(1):e70042. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Dixit P, Srivastava SP, Tiwari SK, Chauhan S, Bishnoi R. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress among nurses after the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ind Psychiatry J. 2024;33(1):54-61. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Bridger KM, Binder JF, Kellezi B. Secondary traumatic stress in foster carers: Risk factors and implications for intervention. J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29(2):482-92. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Koştu N, İnci FH, Arslan S. Compassion fatigue and the meaning in life as predictors of secondary traumatic stress in nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int J Nurs Pract. 2024;30(4):e13249. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Oakley KN, Copel LC, Ross JG. Secondary Traumatic Stress in Nursing Students: An Integrative Review. Nurse Educ. 2025;50(1):E47-52. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Yao J, Zhou X, Xu D, Liu T, Gui Y, Huang Y. Current status and influencing factors of secondary traumatic stress in emergency and intensive care nurses: a cross-sectional analysis. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:567-76. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

12. Gillespie GL, Meyer HA, Daugherty M, Puthoff D, Fryman LJ, Howard PK. Stress and Coping in Emergency Nurses Following Trauma Patient Care: A Qualitative Grounded Theory Approach. J Trauma Nurs. 2024;31(3):136-48. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Alavi SM, Kia-Keating M, Nerenberg C. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in health care providers: A post-disaster study. Traumatol. 2023;29(3):389-401. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

14. Rushforth A, Durk M, Rothwell-Blake GA, Kirkman A, Ng F, Kotera Y. Self-compassion interventions to target secondary traumatic stress in healthcare workers: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(12):6109. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. Koohsari E, Darban F, Safarzai E, Kordi M. Understanding the effect of post-traumatic stress on the professional quality of life of pre-hospital emergency staff. Emerg Nurse. 2021;29(4):33-40. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Jimenez RR, Andersen S, Song H, Townsend C. Vicarious trauma in mental health care providers. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2021;24:100451. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

17. Hajiesmaello M, Hajian S, Riazi H, Majd HA, Yavarian R. Secondary traumatic stress in iranian midwives: stimuli factors, outcomes and risk management.BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):56. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

18. Montero-Tejero DJ, Jiménez-Picón N, Gómez-Salgado J, Vidal-Tejero E, Fagundo-Rivera J. Factors influencing occupational stress perceived by emergency nurses during prehospital care: a systematic review. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:501-28. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

19. Uddin H, Hasan M, Cuartas-Alvarez T, Castro-Delgado R. Effects of mass casualty incidents on anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder among doctors and nurses: a systematic review. Public Health. 2024;234:132-42. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. Jiaru J, Yanxue Z, Wennv H. Incidence of stress among emergency nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(4):e31963. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

21. Comparcini D, Simonetti V, Totaro M, Apicella A, Galli F, Toccaceli A, et al. Impact of Traumatic Stress on Nurses' Work Ability, Job Satisfaction, Turnover and Intention to Leave: A Cross‐Sectional Study. J Adv Nurs. 2025. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

22. Farmahini Farahani M, Jaberi K, Purfarzad Z. Workplace spirituality, compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress: a cross‐sectional study in Iranian nurses. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2023;2023(1):7685791. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

23. Lykins AB, Seroka NW, Mayor M, Seng S, Higgins JT, Okoli CTC. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress among nursing staff at an academic medical center: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2024;30(1):63-73. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

24. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. New York:Sage publications;2014. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

25. Rieger KL. Discriminating among grounded theory approaches. Nurs Inq. 2019;26(1):e12261. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Hamidreza K. Applied qualitative research in health science. Tehran:Jame'e Negar;2024. [View at Publisher]

27. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

28. Linstone HA, Turoff M. The delphi method: Addison-Wesley Reading. MA;1975. [View at Publisher]

29. Fletcher AJ, Marchildon GP. Using the Delphi method for qualitative, participatory action research in health leadership. Int J Qual Methods. 2014;13(1):1-18. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

30. Devenish G, Pollard C, Kerr D. The Delphi process for Public Health Policy Development: five things you need to know. Western Australia:Curtin University;2012. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

31. Beynon P, Chapoy C, Gaarder M, Masset E. What difference does a policy brief make? Full report of an IDS, 3ie, Norad study. Institute of Development Studies and the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie);2012. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

32. DeMarco R, Tufts KA. The mechanics of writing a policy brief. Nurs Outlook. 2014;62(3):219-24. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

33. Felt E, Carrasco JM, Vives-Cases C. [Methodology for the development of policy brief in public health]. Gac Sanit. 2018;32(4):390-2. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

34. Kopenski. Guidelines for Writing a Policy Brief. 2010. [View at Publisher]

35. Ndihokubwayo K. Know How to Write an Influential Policy Brief: A Systematic Guide to Writers and Readers. Journal of Classroom Practices. 2023;2(2):1-10. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

36. Likando GN, Kadhila N. The role of a policy brief in policy formulation and review: bringing evidence to bear. Journal for Studies in Humanities & Social Sciences. 2017;6(2):47. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |