Volume 22, Issue 1 (3-2025)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025, 22(1): 36-42 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Çobanoğlu A. The relationship between the perception of spiritual care and attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care in critical care nurses in northern Turkey. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025; 22 (1) :36-42

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1925-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1925-en.html

Department of Fundamental Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Giresun University, Giresun, Türkiye , asuman.cobanoglu@giresun.edu.tr

Full-Text [PDF 498 kb]

(703 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2171 Views)

Discussion

In this study, the relationship between the level of perception of spirituality and spiritual care and attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care in critical care nurses and the affecting factors were examined. It was determined that the critical care nurses’ perception of spirituality and spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care were at a moderate level. In some of the relevant studies, nurses’ attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care have been determined to be at a moderate level (19,20), while in some studies, their attitudes have been determined to be at a high level (4,17,18,24,29). Spiritual care is an important part of the concept of care which is the focus of the nursing profession and is one of the care interventions that critical care nurses frequently provide. Therefore, spirituality and spiritual care are among the important training subjects that critical care nurses should receive training in. It was determined that the majority of the critical care nurses did not receive any training on spiritual care, which may have affected the nurses’ perception of spiritual care. Even if spirituality and spiritual care are influenced by the individual’s life and cultural background, a decent education can improve nurses’ perceptions and practices regarding spiritual care.

In the study, it was determined that the religiosity subscale of SSCRS was at a higher level compared to other subscales. Considering the results of the study, it can be suggested that critical care nurses value the religious dimension of spirituality, care about religion, focus on religious needs, and provide patient care accordingly. Likewise, in the study conducted by Tan et al. (2018), it was determined that the religiosity subscale of SSCRS was at a higher level compared to other subscales (30). It is known that spiritual care covers all nursing care practices that support patients’ religious practices, personal beliefs, and values; therefore, religion is a fundamental aspect of spirituality. Patient-centered spiritual care should begin with establishing a compassionate relationship that provides hope and comfort, taking into account the individual's beliefs, values, traditions, and practices. This process should be supported by encouraging human contact (31). In a relevant study, it was reported that nurses had difficulty in recognizing the concept of spirituality and could not fully recognize the difference between religion and spirituality (10). However, since spirituality is a larger concept that includes religion but is not limited to religion, it was thought that nurses may lack knowledge about the scope and content of the concept of spirituality and spiritual care.

In the study, although male nurses’ levels of perception of spirituality and spiritual care were found to be higher than those of female nurses, their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care were found to be lower than those of female nurses. This result suggests that nurses' perceptions of spiritual care and end-of-life care may be influenced by factors such as gender roles, emotional involvement, professional experience, and education. While the importance of education and awareness programs in increasing nurses' participation in end-of-life care processes is evident, a more detailed investigation of gender-based differences is required. Contrary to this study, in the study of Karadağ Arli et al. (2016), it was reported that the perception of spirituality and spiritual care was higher in female nurses (32). In a study in which nursing students’ perceptions of spiritual care were evaluated, it was found that female students had a higher level of perception of spiritual care than male students (24). In the study of Efil et al. (2023), it was determined that male nurses had higher levels of attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care (21). In the study, it was observed that there were significant differences in the level of perception of spiritual care of male and female nurses and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. This result demonstrates that although female nurses are traditionally known to undertake the caregiver role more, male nurses also care about spirituality and spiritual care and have positive attitudes toward meeting patients’ spiritual care needs. Furthermore, male nurses’ attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care may be influenced by other factors such as age, professional experience, education, cultural characteristics, and employment.

In the study, it was determined that the level of perception of spirituality and spiritual care and attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care increased as the age and duration of employment of critical care nurses increased. It is known that an increase in professional experience in nursing positively affects the development of critical thinking capacity, different perspectives, and professional skills and competencies (33,34). In line with this information, it can be said that nurses who are older and have more professional experience have more positive perceptions of spiritual care and more positive attitudes and practices toward end-of-life care. The results of some relevant studies support this study finding (1,12,20,29,35-37). In a qualitative study, it was determined that the increased professional experience of nurses employed in palliative care services contributed to the professionalization process and increased professional competencies (34). In contrast to this study, the study by Erzincanlı and Kasar (2022) found that the increase in age and professional experience of intensive care nurses had no effect on their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care (22). Research results may vary due to various factors such as nurses' working conditions and differences in working methods. In other words, we can say that the factors influencing nurses' attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care are multidimensional, and further research is needed in this area.

It has been determined that intensive care nurses who participate in decision-making processes in end-of-life care have higher levels of attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. Similarly, in their study, Erden Melikoğlu et al. (2022) reported that nurses who participated in decision-making processes regarding patient care had higher perceptions of spiritual care (29). According to this result, it can be stated that nurses who participate in decision-making processes in end-of-life care have positive perceptions toward providing effective and holistic care to dying patients. The involvement of nurses in decision-making processes related to end-of-life care demonstrates that they possess a more comprehensive understanding of the subject and play a pivotal role in the management of care.

In the study, it was found that nurses who received training on end-of-life care had more positive attitudes and behaviors toward this care, and that the training had a beneficial effect. This result of the study is consistent with the results of some relevant studies (12,23,38,39). In accordance with this result, one can suggest that nurses with increased knowledge about end-of-life care can positively improve their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care.

In the study, it was observed that critical care nurses who provided end-of-life care every day had higher levels of attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. In their study, Hançerlioğlu and Konakçı (2020) found that nurses who provided end-of-life care every day had higher levels of attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care (12). In another study, it was determined that nurses over the age of 40 who have provided end-of-life care for more than 20 years reflect their end-of-life care experiences at a higher level (38). This finding of our study is consistent with the literature (12,40).

One of the important findings of the study was that there was no correlation between critical care nurses’ perception of spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. Indeed, in a study, it was determined that Turkish intensive care nurses showed more negative attitudes toward family visits of patients receiving end-of-life care compared to European and African intensive care nurses (41).

Limitations: Since this study has a cross-sectional design, the change in critical care nurses’ perceptions of spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care over time could not be determined. Furthermore, since the study was conducted on critical care nurses employed in two hospitals, the results of the study cannot be generalized to all nurses.

Conclusion

This study found no correlation between critical care nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. However, it was determined that increased age, professional experience, and prior training in end-of-life care positively influenced these attitudes and behaviors. This suggests that while age and experience foster positive attitudes toward spiritual care and end-of-life care, perceptions of spiritual care do not significantly impact these attitudes. The findings indicate that other factors, such as cultural and institutional influences, policies, workload, and stress, may also affect nurses' attitudes toward end-of-life care. Based on these results, it is recommended that in-service training programs be developed for critical care nurses, particularly those who are younger and less experienced, to enhance their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care and raise their awareness of spiritual care as a vital aspect of holistic care. Additionally, pairing experienced nurses with less experienced ones could facilitate effective on-the-job training through the transfer of knowledge and skills.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the intensive care nurses who participated in the study.

Funding sources

No financial support was received for this article.

Ethical statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the university’s Ethics Committee, and institutional permission was secured from the organizations where the research was conducted (Date: 06.12.2023, Decision No: 11/21). Verbal and written consent were obtained after participants were fully informed about the study. All ethical principles in human research were upheld, including the right to withdraw from the study, the maintenance of confidentiality, and the protection of participants' identities. The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were adhered to at all stages of the study.

Conflicts of interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology, Data Collection, Data Analysis, Critical Review, Writing the Original Draft, Supervision, Final Approval: Asuman Çobanoğlu.

Full-Text: (468 Views)

Introduction

Nursing care is provided with a holistic approach by evaluating the individual in multiple dimensions, including physical, mental, emotional, sociocultural, and spiritual aspects (1,2). Spiritual care is an important component of holistic care and is one of the important needs to be met, especially for patients receiving end-of-life care. Spirituality is a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek meaning and express themselves. It is often associated with a sense of commitment to oneself, family, community, nature, importance, or the sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices (3). Spiritual care is briefly defined as identifying individuals’ spiritual needs and meeting and supporting them with appropriate interventions. As part of spiritual care, nurses provide services to patients such as therapeutic touch, listening, psychological support, speaking, and comforting (4).

The spiritual care needs of patients increase at the end of life. Therefore, one of the important aspects of end-of-life care is to provide spiritual care to patients. Spiritual concerns and needs that are not met at the end of life can lead to physical and emotional pain in patients (5,6). Critical care nurses are the first witnesses to the spiritual needs of patients in end-of-life care and are responsible for providing spiritual care (7). In previous studies, intensive care patients in need of spiritual care have stated that they valued spirituality and that it was important for them (8). Critical care nurses who are aware of their patients’ spiritual needs can understand them better and provide more effective care (9). Assessing and meeting the spiritual needs of patients at the end of life is considered fundamental for high-quality end-of-life care both in professional and international fields. Guidelines, professional standards, and nursing theories on end-of-life care emphasize the importance of spiritual care (7). If the spiritual care needs of patients are not met, holistic palliative and end-of-life care cannot be provided (10). Therefore, critical care nurses’ spiritual care and end-of-life care practices are important in providing and maintaining holistic care.

One of the most difficult and challenging aspects of the nursing profession is providing end-of-life care. Mortality in intensive care units has been reported to be approximately 21.3% (11) and end-of-life care is one of the important care practices performed by critical care nurses (12). While providing end-of-life care to patients and confronting the concept of death, critical care nurses must sustain care practices for dying individuals and their families (13,14). Critical care nurses should provide pain-free and high-quality care to patients from the end of life until death (15). In end-of-life care, critical care nurses should provide care through evidence-based practices by evaluating patients holistically with their social, psychological, biological, cultural, and spiritual aspects (11). In end-of-life care, they should control pain, empathize, coordinate the death process, encourage the patient to talk, listen to the patient, evaluate anxiety, and provide spiritual care (16).

In some studies, conducted on the subject, nurses’ perception of spiritual care has been reported to be high (17,18), while in some studies, it has been found to be at a moderate level (19,20). In the related literature, there are study findings showing that nurses' attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care are at a moderate level (21,22). In the literature, there are research results on the perception of spiritual care of critical care nurses (4,20) and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care (12,23); however, there are no studies in which the relationship between nurses’ perception of spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care has been explored. The way critical care nurses perceive spirituality and spiritual care, how much they reflect it in their practices, the way they support patients’ spiritual needs, and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care are very important. Critical care nurses can provide holistic care to patients by optimizing these factors and can contribute to a quality recovery process. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the relationship between critical care nurses’ perceptions of spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care.

Methods

This cross-sectional and correlational study was conducted in two state hospitals from May 2024 to July 2024. The study population consisted of critical care nurses working in the intensive care units of two state hospitals in northern Turkey (N = 315). The sample size was calculated using G*power version 3.1.9.7 for multiple regression analyses. The minimum required sample size was determined to be 171, based on eight predictor variables, a power of 0.95, a significance level of 0.05, and a medium effect size (f2) of 0.15 for two-tailed tests. In this study, no sampling method was employed; instead, the entire population was included through census sampling (19). Since 112 nurses did not want to participate in the study, 12 were on leave, and 17 delivered incomplete data collection forms, they were excluded from the study. A total of 174 critical care nurses were included in the study sample. The inclusion criteria were being employed as a nurse in the intensive care unit for at least one year and volunteering to participate in the study. Critical care nurses who were on leave or sick leave during the data collection process and did not agree to participate in the study were excluded from the study.

The research data were collected using a Nurse Introduction Form, the Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS), and the End-of-Life Care Attitudes and Behaviors Scale (EACAS) of Intensive Care Nurses.

Nurse introduction form: The form was created by the researcher in line with the literature (17,19,24). It consists of three sections and a total of 13 questions regarding demographic characteristics (Age, sex, marital status) and occupational status of nurses, and regarding end-of-life care and spiritual care.

Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS): The scale was developed by McSherry, Draper, and Kendrick in 2002 to measure nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care (25). The Turkish validity and reliability tests of the scale were carried out by Ergül and Temel (2007) and the Cronbach alpha coefficient was found to be 0.76 (26). The scale is a five-point Likert-type scale consisting of spirituality and spiritual care, religiosity, and individualized care subscales. The items are scored from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). On the scale, items 3, 4, 13, and 16 include reverse statements. A mean total score approaching 5 indicates an increase in the perception of spirituality and delivery of spiritual care (26). In general, higher scores indicate a greater perception of spirituality or provision of spiritual care. In this study, the Cronbach alpha was 0.64.

End-of-Life Care Attitudes and Behaviors Scale (EACAS) of intensive care nurses: The scale was developed by Zomorodi in 2008 (27). Its Turkish validity and reliability were established by Özel Yalçınkaya in 2016 (28). The scale has two subscales: attitudes of intensive care nurses toward end-of-life care and behaviors of intensive care nurses toward end-of-life care. The attitude subscale consists of ten items and the behavior subscale consists of six items, totaling 16 items. Only the 8th question from the attitude subscale is reverse coded. The other items are scored from 1 to 5, and it is interpreted that the attitudes and behavior will be positive as the score increases. However, since the 8th item has a negative meaning, it is reverse coded. The attitude subscale is assessed on a five-point Likert-type scale as “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “partially disagree”, “agree”, and “strongly agree”. The behavior subscale is evaluated on a five-point Likert-type scale as “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “usually”, and “always”. The highest score to be obtained from the scale in total is 80, while the lowest score is 16. As the scale score increases, it is interpreted that attitudes and behaviors will be positive (28). In this study, the Cronbach alpha was 0.70.

The scope and purpose of the study and rights of the participants were comprehensively explained to the critical care nurses by the researcher. The critical care nurses who agreed to participate in the study were informed about how to fill out the data collection form and their verbal and written consent was taken. The nurses were asked to fill in all the questions in the data collection form as they thought appropriate and completed the forms independently at an appropriate time. The researcher collected the forms completed by the nurses between 08.00 and 16.00 on weekdays. Each participant completed the forms in approximately 15 minutes.

Statistical analysis

The study data were analyzed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) for Windows 25.0 program (IBM Corp; Armonk, NY, USA). Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess fitness for normal distribution. Descriptive statistics (Frequencies, percentages, mean, minimum, and maximum values), Mann Whitney U test, and Kruskal Wallis test were used for statistical analysis of the data. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between the scale scores. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to determine whether the independent variables predicted the dependent variable. Statistical significance was determined as p <0.05.

Results

The mean age of the critical care nurses included in the study was 34.60 ± 7.59 years. Of the nurses, 83.9% were female and 69.5% were married. The duration of professional experience was 10.41 ± 7.57 years and the duration of intensive care nursing experience was 6.60 ± 4.54 years. Of the nurses, 87.9% had a bachelor’s degree and 25.3% were employed in the Anesthesia and Reanimation Intensive Care Unit (Table 1). Among the critical care nurses, 66.7% did not receive training on spiritual care and 38.1% did not receive training on end-of-life care. Of the nurses, 81% thought that they met the spiritual care and end-of-life care needs of their patients, 59.8% did not participate in decision-making processes in end-of-life care, and 36.2% provided end-of-life care once a week (Table 2).

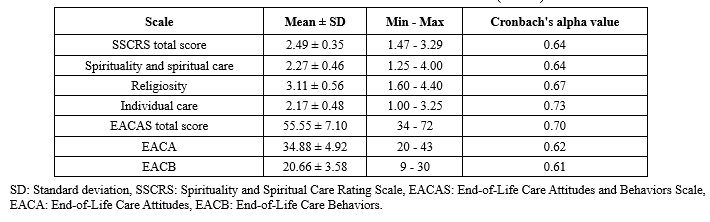

The mean total score of the critical care nurses on SSCRS was 2.49 ± 0.35. The mean subscale scores of the nurses were 2.27 ± 0.46 for the Spirituality and Spiritual Care subscale, 3.11 ± 0.56 for the Religiosity subscale, and 2.17 ± 0.48 for the individualized care subscale. The mean total score of the critical care nurses on EACAS was 55.55 ± 7.10. The mean score on the Attitude subscale was 34.88 ± 4.92 and the mean score on the Behavior subscale was 20.66 ± 3.58 (Table 3).

There was a significant difference between nurses’ sex (p = 0.03), duration of employment (p = 0.030), status of meeting the spiritual care needs of patients (p = 0.032), and frequency of providing end-of-life care (p = 0.001) and the mean total SSCRS score. There was a significant difference between the nurses’ duration of employment (p = 0.009), status of receiving training on end-of-life care (p = 0.00), status of participating in decision-making processes in end-of-life care (p=0.009), and status of meeting the end-of-life (p = 0.000) and spiritual care needs of patients and their mean total EACAS score (p = 0.006) (Table 2).

While there was no significant correlation between the scores of the critical care nurses on SSCRS and its subscales and their score on EACAS (r = -0.063, p = 0.408), there was a weak positive correlation between age (r = 0.224, p = 0.003) and professional experience (r = 0.189, p = 0.013) and the EACAS score (Table 4). In the study, hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to determine the effect of demographic and descriptive characteristics and SSCRS scores of critical care nurses on their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. Table 5 shows Model 1, age, sex, marital status, and income status explained 5% of the attitudes and behaviors of critical care nurses toward end-of-life care (F = 2.550, p = 0.040). The age variable was significantly associated (β = 0.13, p = 0.000) (Table 5).

Nursing care is provided with a holistic approach by evaluating the individual in multiple dimensions, including physical, mental, emotional, sociocultural, and spiritual aspects (1,2). Spiritual care is an important component of holistic care and is one of the important needs to be met, especially for patients receiving end-of-life care. Spirituality is a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek meaning and express themselves. It is often associated with a sense of commitment to oneself, family, community, nature, importance, or the sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices (3). Spiritual care is briefly defined as identifying individuals’ spiritual needs and meeting and supporting them with appropriate interventions. As part of spiritual care, nurses provide services to patients such as therapeutic touch, listening, psychological support, speaking, and comforting (4).

The spiritual care needs of patients increase at the end of life. Therefore, one of the important aspects of end-of-life care is to provide spiritual care to patients. Spiritual concerns and needs that are not met at the end of life can lead to physical and emotional pain in patients (5,6). Critical care nurses are the first witnesses to the spiritual needs of patients in end-of-life care and are responsible for providing spiritual care (7). In previous studies, intensive care patients in need of spiritual care have stated that they valued spirituality and that it was important for them (8). Critical care nurses who are aware of their patients’ spiritual needs can understand them better and provide more effective care (9). Assessing and meeting the spiritual needs of patients at the end of life is considered fundamental for high-quality end-of-life care both in professional and international fields. Guidelines, professional standards, and nursing theories on end-of-life care emphasize the importance of spiritual care (7). If the spiritual care needs of patients are not met, holistic palliative and end-of-life care cannot be provided (10). Therefore, critical care nurses’ spiritual care and end-of-life care practices are important in providing and maintaining holistic care.

One of the most difficult and challenging aspects of the nursing profession is providing end-of-life care. Mortality in intensive care units has been reported to be approximately 21.3% (11) and end-of-life care is one of the important care practices performed by critical care nurses (12). While providing end-of-life care to patients and confronting the concept of death, critical care nurses must sustain care practices for dying individuals and their families (13,14). Critical care nurses should provide pain-free and high-quality care to patients from the end of life until death (15). In end-of-life care, critical care nurses should provide care through evidence-based practices by evaluating patients holistically with their social, psychological, biological, cultural, and spiritual aspects (11). In end-of-life care, they should control pain, empathize, coordinate the death process, encourage the patient to talk, listen to the patient, evaluate anxiety, and provide spiritual care (16).

In some studies, conducted on the subject, nurses’ perception of spiritual care has been reported to be high (17,18), while in some studies, it has been found to be at a moderate level (19,20). In the related literature, there are study findings showing that nurses' attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care are at a moderate level (21,22). In the literature, there are research results on the perception of spiritual care of critical care nurses (4,20) and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care (12,23); however, there are no studies in which the relationship between nurses’ perception of spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care has been explored. The way critical care nurses perceive spirituality and spiritual care, how much they reflect it in their practices, the way they support patients’ spiritual needs, and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care are very important. Critical care nurses can provide holistic care to patients by optimizing these factors and can contribute to a quality recovery process. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the relationship between critical care nurses’ perceptions of spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care.

Methods

This cross-sectional and correlational study was conducted in two state hospitals from May 2024 to July 2024. The study population consisted of critical care nurses working in the intensive care units of two state hospitals in northern Turkey (N = 315). The sample size was calculated using G*power version 3.1.9.7 for multiple regression analyses. The minimum required sample size was determined to be 171, based on eight predictor variables, a power of 0.95, a significance level of 0.05, and a medium effect size (f2) of 0.15 for two-tailed tests. In this study, no sampling method was employed; instead, the entire population was included through census sampling (19). Since 112 nurses did not want to participate in the study, 12 were on leave, and 17 delivered incomplete data collection forms, they were excluded from the study. A total of 174 critical care nurses were included in the study sample. The inclusion criteria were being employed as a nurse in the intensive care unit for at least one year and volunteering to participate in the study. Critical care nurses who were on leave or sick leave during the data collection process and did not agree to participate in the study were excluded from the study.

The research data were collected using a Nurse Introduction Form, the Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS), and the End-of-Life Care Attitudes and Behaviors Scale (EACAS) of Intensive Care Nurses.

Nurse introduction form: The form was created by the researcher in line with the literature (17,19,24). It consists of three sections and a total of 13 questions regarding demographic characteristics (Age, sex, marital status) and occupational status of nurses, and regarding end-of-life care and spiritual care.

Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale (SSCRS): The scale was developed by McSherry, Draper, and Kendrick in 2002 to measure nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care (25). The Turkish validity and reliability tests of the scale were carried out by Ergül and Temel (2007) and the Cronbach alpha coefficient was found to be 0.76 (26). The scale is a five-point Likert-type scale consisting of spirituality and spiritual care, religiosity, and individualized care subscales. The items are scored from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). On the scale, items 3, 4, 13, and 16 include reverse statements. A mean total score approaching 5 indicates an increase in the perception of spirituality and delivery of spiritual care (26). In general, higher scores indicate a greater perception of spirituality or provision of spiritual care. In this study, the Cronbach alpha was 0.64.

End-of-Life Care Attitudes and Behaviors Scale (EACAS) of intensive care nurses: The scale was developed by Zomorodi in 2008 (27). Its Turkish validity and reliability were established by Özel Yalçınkaya in 2016 (28). The scale has two subscales: attitudes of intensive care nurses toward end-of-life care and behaviors of intensive care nurses toward end-of-life care. The attitude subscale consists of ten items and the behavior subscale consists of six items, totaling 16 items. Only the 8th question from the attitude subscale is reverse coded. The other items are scored from 1 to 5, and it is interpreted that the attitudes and behavior will be positive as the score increases. However, since the 8th item has a negative meaning, it is reverse coded. The attitude subscale is assessed on a five-point Likert-type scale as “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “partially disagree”, “agree”, and “strongly agree”. The behavior subscale is evaluated on a five-point Likert-type scale as “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “usually”, and “always”. The highest score to be obtained from the scale in total is 80, while the lowest score is 16. As the scale score increases, it is interpreted that attitudes and behaviors will be positive (28). In this study, the Cronbach alpha was 0.70.

The scope and purpose of the study and rights of the participants were comprehensively explained to the critical care nurses by the researcher. The critical care nurses who agreed to participate in the study were informed about how to fill out the data collection form and their verbal and written consent was taken. The nurses were asked to fill in all the questions in the data collection form as they thought appropriate and completed the forms independently at an appropriate time. The researcher collected the forms completed by the nurses between 08.00 and 16.00 on weekdays. Each participant completed the forms in approximately 15 minutes.

Statistical analysis

The study data were analyzed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) for Windows 25.0 program (IBM Corp; Armonk, NY, USA). Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess fitness for normal distribution. Descriptive statistics (Frequencies, percentages, mean, minimum, and maximum values), Mann Whitney U test, and Kruskal Wallis test were used for statistical analysis of the data. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between the scale scores. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to determine whether the independent variables predicted the dependent variable. Statistical significance was determined as p <0.05.

Results

The mean age of the critical care nurses included in the study was 34.60 ± 7.59 years. Of the nurses, 83.9% were female and 69.5% were married. The duration of professional experience was 10.41 ± 7.57 years and the duration of intensive care nursing experience was 6.60 ± 4.54 years. Of the nurses, 87.9% had a bachelor’s degree and 25.3% were employed in the Anesthesia and Reanimation Intensive Care Unit (Table 1). Among the critical care nurses, 66.7% did not receive training on spiritual care and 38.1% did not receive training on end-of-life care. Of the nurses, 81% thought that they met the spiritual care and end-of-life care needs of their patients, 59.8% did not participate in decision-making processes in end-of-life care, and 36.2% provided end-of-life care once a week (Table 2).

The mean total score of the critical care nurses on SSCRS was 2.49 ± 0.35. The mean subscale scores of the nurses were 2.27 ± 0.46 for the Spirituality and Spiritual Care subscale, 3.11 ± 0.56 for the Religiosity subscale, and 2.17 ± 0.48 for the individualized care subscale. The mean total score of the critical care nurses on EACAS was 55.55 ± 7.10. The mean score on the Attitude subscale was 34.88 ± 4.92 and the mean score on the Behavior subscale was 20.66 ± 3.58 (Table 3).

There was a significant difference between nurses’ sex (p = 0.03), duration of employment (p = 0.030), status of meeting the spiritual care needs of patients (p = 0.032), and frequency of providing end-of-life care (p = 0.001) and the mean total SSCRS score. There was a significant difference between the nurses’ duration of employment (p = 0.009), status of receiving training on end-of-life care (p = 0.00), status of participating in decision-making processes in end-of-life care (p=0.009), and status of meeting the end-of-life (p = 0.000) and spiritual care needs of patients and their mean total EACAS score (p = 0.006) (Table 2).

While there was no significant correlation between the scores of the critical care nurses on SSCRS and its subscales and their score on EACAS (r = -0.063, p = 0.408), there was a weak positive correlation between age (r = 0.224, p = 0.003) and professional experience (r = 0.189, p = 0.013) and the EACAS score (Table 4). In the study, hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to determine the effect of demographic and descriptive characteristics and SSCRS scores of critical care nurses on their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. Table 5 shows Model 1, age, sex, marital status, and income status explained 5% of the attitudes and behaviors of critical care nurses toward end-of-life care (F = 2.550, p = 0.040). The age variable was significantly associated (β = 0.13, p = 0.000) (Table 5).

Table 1. Critical care nurses’ demographic and descriptive characteristics (n = 174).PNG) Table 2. Variables affecting the mean scores of critical care nurses' EACAS and SSCRS (n = 174) .PNG) |

Critical care nurses’ duration of employment, status of participating in decision-making processes in end-of-life care, status of receiving training on spiritual care, and status of receiving training on end-of-life care were added to Model 2 (Table 5). Among these variables, there was a significant positive correlation between the status of receiving training on end-of-life care and the attitudes and behaviors of critical care nurses toward end-of-life care (β = 0.399, p = 0.000) (Table 5). In the last stage, SSCRS was added to the model. In Model 3, there was no significant correlation between SSCRS and the attitudes and behaviors of critical care nurses toward end-of-life care (β = -0.07, p = 0.342) (Table 5).

Table 3. Critical care nurses’ mean scores of SSCRS and EACAS (n = 174)  Table 4. The Pearson correlation coefficients between SSCSR and EACAS (n = 174)  Table 5. Results of hierarchical multiple regression analysis regarding the prediction of attitudes and behaviors of critical care nurses toward end-of-life care (n = 174) .PNG) |

Discussion

In this study, the relationship between the level of perception of spirituality and spiritual care and attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care in critical care nurses and the affecting factors were examined. It was determined that the critical care nurses’ perception of spirituality and spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care were at a moderate level. In some of the relevant studies, nurses’ attitudes toward spirituality and spiritual care have been determined to be at a moderate level (19,20), while in some studies, their attitudes have been determined to be at a high level (4,17,18,24,29). Spiritual care is an important part of the concept of care which is the focus of the nursing profession and is one of the care interventions that critical care nurses frequently provide. Therefore, spirituality and spiritual care are among the important training subjects that critical care nurses should receive training in. It was determined that the majority of the critical care nurses did not receive any training on spiritual care, which may have affected the nurses’ perception of spiritual care. Even if spirituality and spiritual care are influenced by the individual’s life and cultural background, a decent education can improve nurses’ perceptions and practices regarding spiritual care.

In the study, it was determined that the religiosity subscale of SSCRS was at a higher level compared to other subscales. Considering the results of the study, it can be suggested that critical care nurses value the religious dimension of spirituality, care about religion, focus on religious needs, and provide patient care accordingly. Likewise, in the study conducted by Tan et al. (2018), it was determined that the religiosity subscale of SSCRS was at a higher level compared to other subscales (30). It is known that spiritual care covers all nursing care practices that support patients’ religious practices, personal beliefs, and values; therefore, religion is a fundamental aspect of spirituality. Patient-centered spiritual care should begin with establishing a compassionate relationship that provides hope and comfort, taking into account the individual's beliefs, values, traditions, and practices. This process should be supported by encouraging human contact (31). In a relevant study, it was reported that nurses had difficulty in recognizing the concept of spirituality and could not fully recognize the difference between religion and spirituality (10). However, since spirituality is a larger concept that includes religion but is not limited to religion, it was thought that nurses may lack knowledge about the scope and content of the concept of spirituality and spiritual care.

In the study, although male nurses’ levels of perception of spirituality and spiritual care were found to be higher than those of female nurses, their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care were found to be lower than those of female nurses. This result suggests that nurses' perceptions of spiritual care and end-of-life care may be influenced by factors such as gender roles, emotional involvement, professional experience, and education. While the importance of education and awareness programs in increasing nurses' participation in end-of-life care processes is evident, a more detailed investigation of gender-based differences is required. Contrary to this study, in the study of Karadağ Arli et al. (2016), it was reported that the perception of spirituality and spiritual care was higher in female nurses (32). In a study in which nursing students’ perceptions of spiritual care were evaluated, it was found that female students had a higher level of perception of spiritual care than male students (24). In the study of Efil et al. (2023), it was determined that male nurses had higher levels of attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care (21). In the study, it was observed that there were significant differences in the level of perception of spiritual care of male and female nurses and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. This result demonstrates that although female nurses are traditionally known to undertake the caregiver role more, male nurses also care about spirituality and spiritual care and have positive attitudes toward meeting patients’ spiritual care needs. Furthermore, male nurses’ attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care may be influenced by other factors such as age, professional experience, education, cultural characteristics, and employment.

In the study, it was determined that the level of perception of spirituality and spiritual care and attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care increased as the age and duration of employment of critical care nurses increased. It is known that an increase in professional experience in nursing positively affects the development of critical thinking capacity, different perspectives, and professional skills and competencies (33,34). In line with this information, it can be said that nurses who are older and have more professional experience have more positive perceptions of spiritual care and more positive attitudes and practices toward end-of-life care. The results of some relevant studies support this study finding (1,12,20,29,35-37). In a qualitative study, it was determined that the increased professional experience of nurses employed in palliative care services contributed to the professionalization process and increased professional competencies (34). In contrast to this study, the study by Erzincanlı and Kasar (2022) found that the increase in age and professional experience of intensive care nurses had no effect on their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care (22). Research results may vary due to various factors such as nurses' working conditions and differences in working methods. In other words, we can say that the factors influencing nurses' attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care are multidimensional, and further research is needed in this area.

It has been determined that intensive care nurses who participate in decision-making processes in end-of-life care have higher levels of attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. Similarly, in their study, Erden Melikoğlu et al. (2022) reported that nurses who participated in decision-making processes regarding patient care had higher perceptions of spiritual care (29). According to this result, it can be stated that nurses who participate in decision-making processes in end-of-life care have positive perceptions toward providing effective and holistic care to dying patients. The involvement of nurses in decision-making processes related to end-of-life care demonstrates that they possess a more comprehensive understanding of the subject and play a pivotal role in the management of care.

In the study, it was found that nurses who received training on end-of-life care had more positive attitudes and behaviors toward this care, and that the training had a beneficial effect. This result of the study is consistent with the results of some relevant studies (12,23,38,39). In accordance with this result, one can suggest that nurses with increased knowledge about end-of-life care can positively improve their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care.

In the study, it was observed that critical care nurses who provided end-of-life care every day had higher levels of attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. In their study, Hançerlioğlu and Konakçı (2020) found that nurses who provided end-of-life care every day had higher levels of attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care (12). In another study, it was determined that nurses over the age of 40 who have provided end-of-life care for more than 20 years reflect their end-of-life care experiences at a higher level (38). This finding of our study is consistent with the literature (12,40).

One of the important findings of the study was that there was no correlation between critical care nurses’ perception of spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. Indeed, in a study, it was determined that Turkish intensive care nurses showed more negative attitudes toward family visits of patients receiving end-of-life care compared to European and African intensive care nurses (41).

Limitations: Since this study has a cross-sectional design, the change in critical care nurses’ perceptions of spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care over time could not be determined. Furthermore, since the study was conducted on critical care nurses employed in two hospitals, the results of the study cannot be generalized to all nurses.

Conclusion

This study found no correlation between critical care nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care and their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care. However, it was determined that increased age, professional experience, and prior training in end-of-life care positively influenced these attitudes and behaviors. This suggests that while age and experience foster positive attitudes toward spiritual care and end-of-life care, perceptions of spiritual care do not significantly impact these attitudes. The findings indicate that other factors, such as cultural and institutional influences, policies, workload, and stress, may also affect nurses' attitudes toward end-of-life care. Based on these results, it is recommended that in-service training programs be developed for critical care nurses, particularly those who are younger and less experienced, to enhance their attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care and raise their awareness of spiritual care as a vital aspect of holistic care. Additionally, pairing experienced nurses with less experienced ones could facilitate effective on-the-job training through the transfer of knowledge and skills.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the intensive care nurses who participated in the study.

Funding sources

No financial support was received for this article.

Ethical statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the university’s Ethics Committee, and institutional permission was secured from the organizations where the research was conducted (Date: 06.12.2023, Decision No: 11/21). Verbal and written consent were obtained after participants were fully informed about the study. All ethical principles in human research were upheld, including the right to withdraw from the study, the maintenance of confidentiality, and the protection of participants' identities. The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were adhered to at all stages of the study.

Conflicts of interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology, Data Collection, Data Analysis, Critical Review, Writing the Original Draft, Supervision, Final Approval: Asuman Çobanoğlu.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. Esendir İN, Kaplan H. [Perception of spirituality and spiritual support among health care professionals: The example of İstanbul]. Ekev Academy Dergisi. 2018;73:317-32. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

2. Wu LF, Tseng HC, Liao YC. Nurse education and willingness to provide spiritual care. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;38:36-41. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. de Brito Sena MA, Damiano RF, Lucchetti G, Peres MFP. Defining spirituality in healthcare: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Front Psychol. 2021;12:756080. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Bakır E, Samancioglu S, Kilic SP. Spiritual experiences of muslim critical care nurses. J Relig Health. 2017;56(6):2118-28. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Edwars A, Pang N, Shiu V, Chan C. The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: A meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med. 2010;24(8):753-70. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. García-Navarro EB, Medina-Ortega A, García Navarro S. Spirituality in patients at the end of life-is it necessary? A qualitative approach to the protagonists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19(1):227. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Batstone E, Bailey C, Hallett N. Spiritual care provision to end-of-life patients: A systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(19-20):3609-24. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Aslakson RA, Kweku J, Kinnison M, Singh S, Crowe II TY. Operationalizing the measuring what matters spirituality quality metric in a population of hospitalized, critically ill patients and their family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(3):650-5. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Tüzer H, Kırca K, Özveren H. Investigation of nursing students' attitudes towards death and their perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care. J Relig Health. 2020;59(4):2177-90. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. O'Brien MR, Kinloch K, Groves KE, Jack BA. Meeting patients' spiritual needs during end-of-life care: A qualitative study of nurses' and healthcare professionals perceptions of spiritual care training. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(1-2):182-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC). Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre; Reporting. 2021. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

12. Hançerlioğlu S, Konakçı G. The attitudes and behaviors of intensive care unit nurses towards end-of-life care. Health Res J. 2020;6(3):93-100. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

13. Çifci A. [End of life and palliative care]. J Med Palliat Care. 2021;2(1):21-4. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

14. Şahin M. Nursing students' death anxiety, influencing factors and request of caring for dying people. J Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;7(3):135-41. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

15. Yeloğlu ÇH, Güveli H, Hocaoğlu Ç. [Psychiatric approach in terminaly ill patients]. Literatür Sempozyum. 2014;43-50. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

16. Ay MA. Hemşirelerin ölüm, ölümcül hasta ve ötenaziye ilişkin tutumları. [Thesis] [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

17. Aktaş G, Keskin Güleç S. [Investigation of the relationship between the professional self concept and spiritual care of clinical nurses]. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Elektronik Dergisi. 2023;16(1):79-91. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

18. Özcan T, Çilingir D, Candaş Altınbaş B. The knowledge, practices, and perceptions of surgical nurses concerning spirituality and spiritual care. J Perianesth Nurs. 2023;38(5):732-7. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

19. Ercan F, Körpe G, Demir S. Spirituality and spiritual care related perceptions of nurses working at the inpatient services of a university hospital. Gazi Med J. 2018;29(1):17-22. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

20. Taheri-Kharameh Z, Asayesh H, Shariffifard F, Alinnoori A. Attitude toward spiritualty, spiritual care, and its relationship with mental health among intensive care nurses. Health Spiritual Med Ethics. 2016;3(3):25-9. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

21. Efil S, Turen S, Demir G. Relationship between intensive care nuırses' attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care and ethical attitudes. Dimens Crit Care Nur. 2023;42(6):325-32. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

22. Erzincanlı S, Kasar KS. The effects of nurses' attitudes and behaviors toward end-of-life care on clinical decision-making. J Turk Soc Intens Care. 2022;20(4):230-7. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

23. Cengiz Z, Yıldırım H, Kömürkara S. [How does self-realization in nurses affect attitudes and behaviors towards palliative care?] İnönü Üniversitesi Sağlık Hizmetleri Meslek Yüksek Okulu Dergisi. 2020;8(3):578-89. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

24. Akkuş Y, Karabağ Aydın A. Determining the relationship between spirituality and perceptions of care in nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2022;58(4):2079-87. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

25. McSherry W, Draper P, Kendrick D. The construct validity of a rating scale designed to assess spirituality and spiritual care. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39(7):723-34. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Ergül S, Temel AB. [Validity and reliability of 'The Spirituality and Spiritual Care Rating Scale' Turkish version]. Ege Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Yüksekokulu Dergisi. 2007;23(1):75-87. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

27. Zomorodi M, Lynn MR. Instrument development measuring critical care nurses' attitudes and behaviors with end-of-life care. Nurs Res. 2010;59(4):234-240. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

28. Özel Yalçınkaya S. Yoğun bakım hemşirelerinin yaşam sonu bakıma yönelik tutum ve davranışları ölçeği'nin Türk kültürüne uyarlanması: geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Abant İzzet Baysal University Institute of Health Sciences. 2016. [Thesis] [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

29. Erden Melikoğlu S, Köktürk Dalcalı B, Güngörmüş E, Kaya H. The relationship between the individualized care perceptions and spiritual care perceptions of nurses. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2022;58(4):1712-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

30. Tan M, Ozdelikara A, Polat H. An exploratory study of spirituality and spiritual care among Turkey nurses. Int J Caring Sci. 2018;11(2):1311-8. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

31. Kang, KA, Chun J, Kim HY, Kim HY. Hospice palliative care nurses' perceptions of spiritual care and their spiritual care competence: A mixed‐methods study. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(7-8):961-74. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

32. Karadağ Arli S, Bakan AB, Erisik E. An investigation of the relationship between nurses' views on spirituality and spiritual care and their level of burnout. J Holist Nurs. 2017;35(3):214-20. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

33. Ertürk C, Özmen D. [Determination the variables that predicting the professional attitudes of nurses]. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Elektronik Dergisi. 2018;11(3):191-9. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

34. Okçin F. Onkoloji palyatif bakım hemşirelerinin mesleki yaşam deneyimlerinin incelenmesi. Celal Bayar Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü Dergisi. 2019;6(4):234-46. [View at Publisher] [DOI]

35. Kaddourah B, Abu‐Shaheen A, Al‐Tannir M. Nurses' perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care at five tertiary care hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A cross‐sectional study. Oman Med J. 2018;33(2):154-8. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

36. Yildirim JG, Ertem M. Professional quality of life and perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care among nurses: Relationship and affecting factors. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;58(2):438-47. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

37. Hussin EOD, Wong LP, Chong MC, Subramanian P. Factors associated with nurses' perceptions about quality of end‐of‐life care. Int Nurs Rev. 2018;65(2):200-8. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

38. Gupta M, Pruthi G, Gupta P, Singh K, Kanwat J, Tiwari A. Impact of end-of-life nursing education consortium on palliative care knowledge and attitudes towards care of dying of nurses in India: A quasi-experimental pre-post study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2023;40(5):529-38. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

39. Chu E-Y, Jang S-H. The effects of a death preparation education program on death anxiety, death attitudes, and attitudes toward end-of-life care among nurses in convalescent hospitals. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;24(3):154-64. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

40. Abu Hasheesh MO, AboZeid SAS, El-Said SG, Alhujaili AD. Nurses' characteristics and their attitudes toward death and caring for dying patients in a public hospital in Jordan. Health Sci J. 2013;7(4):384-94. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

41. Tripathy S, Routray PK, Mishra JC. Intensive care nurses' attitude on palliative and end of life care. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21(10):655-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |