Volume 20, Issue 2 (10-2023)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2023, 20(2): 58-62 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: 016/2563

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Wongpiomoln B, Sayuen C, Pholputta L, Phengphol N. Design, implementation, and evaluation of Youth Peer Support Training to improve quality of life and stress among homebound and bedridden older adults. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2023; 20 (2) :58-62

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1569-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1569-en.html

1- Division of Adult and Gerontological Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Roi Et Rajabhat University, Thailand

2- Division of Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Roi Et Rajabhat University, Thailand ,chanidatoi@reru.ac.th

2- Division of Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Roi Et Rajabhat University, Thailand ,

Keywords: Program development, Quality of life, Stress disorders, Homebound persons, Bedridden persons, Mixed method

Full-Text [PDF 569 kb]

(1259 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3416 Views)

Full-Text: (451 Views)

Introduction

The number and proportion of people aged 60 years or older is rapidly increasing worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, there were 1 billion people aged 60 or older in 2019. The number of older adults is expected to increase to 1.4 billion by 2030 and 2.1 billion by 2050 (1). An increase in the older adult population in Thailand has increased the proportion of homebound and bedridden older adults. As the aging population rapidly grows and rates of chronic diseases increase, caring for them poses many challenges to both the government and families (2,3). In addition, the number of homebound and bedridden individuals is expected to be 321,511 and 152,749, respectively, by 2030. The number of bedridden older adults will reach 153,000 in the next decade (4). Meanwhile, the current global demographic situation is characterized by an increase in average life expectancy and a low birth rate, as well as a growing number of older adults (5).

At the same time, older adults live longer. They are facing the deterioration of physical and psychological health. Older adults are more likely to suffer from chronic conditions and multi-morbidities, and their functional capacity is frequently limited (6). Importantly, older adults can stress on their health related to quality of life (7). Homebound and bedridden older adults need health care from health care providers and family members, as well as community participation, to improve their health. Health care is important to slow down deterioration, reduce chronic illness, reduce expenses caused by illness, and increase the level of activities of daily living by enabling older adults to live happily, resulting in a good quality of life (6, 8, 9). Being homebound and bedridden can affect older adults’ physical and mental health by decreasing movement, which can itself be exacerbated by the deterioration of older adults’ health.(10,11) As a result, older adults will age in their own homes, and the majority of them have one or more chronic disorders, depression, and stress (12-14). Thus, health problems can affect the quality of life among homebound and bedridden older adults (11).

With the changing trend of population structure in Thai society, as economic and demographic changes occur, family size is getting smaller; in addition, approximately one-third of the older adults are under the poverty line. Conversely, there is a growing population of elderly individuals who are homebound or bedridden, facing financial insecurity, while the availability of family caregivers is decreasing (3). Some older adults who live alone are vulnerable physically, emotionally, and socially (15). Spouses and children constitute approximately 90% of the main caregivers for older adults. Thus, informal caregivers play a significant role in caring for older adults. On the other hand, their knowledge, practice, and needs in older adults caring are weak and poorly characterized (16,17). However, the Thai government has put considerably more effort into establishing and developing long-term care policies to provide home care and social support for homebound and bedridden older adults. The health volunteers and elderly home care volunteers will work closely together with subdistrict health-promoting hospitals or local governments to provide essential medical and social support to older adults with disabilities in their communities (3). Nevertheless, the number of caregivers is still insufficient; thus, young individuals in the community are another important group that should provide health care for homebound and bedridden older adults.

In rural northeastern Thai society, young individuals are descendants of older adults in the community who want to take care of their fathers, mothers, grandfathers, and grandmothers both in the present and future. In addition, according to the myth of a uniquely caring Thai society, they need to further participate with the community to take care of older adults in their community. The program aims to enhance knowledge, cultivate essential caregiving skills for homebound and bedridden older adults, foster a positive mindset in young individuals, and establish an elderly-friendly environment through the support of health volunteers. Ultimately, this leads to an improved quality of life for homebound and bedridden older adults. Consequently, the researchers were interested in conducting research. This study hypothesized that the participation of homebound and bedridden older adults in the training program could enhance their quality of life and reduce stress. This study aimed to develop a program for homebound and bedridden older adults using peer support from health volunteers to educate and support youth in Tha-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand.

Methods

Design

This study is part of a larger research and development project conducted from February to June 2020, employing mixed methods research. The project was conducted in 3 steps as follows: 1) exploration of the current situation using a qualitative method, 2) development of a training program, and 3) implementation and evaluation of a program developed through a quasi-experimental method. The detailed results regarding the involvement of youth in step 3 were published in a nursing journal in Thailand (18). The current paper presents only the issue among homebound and bedridden older adults.

Step 1: Exploration of the current situation among homebound and bedridden older adults

The researcher investigated several documents and studies concerning concepts and theories related to health care among homebound and bedridden older adults. Based on the literature review, in-depth interviews and focus group discussions were used to analyze the community context and the need for health care among homebound and bedridden older adults. The participants were 20 stakeholders, consisting of 1 local government organization, 2 community leaders, 2 older adults from elderly clubs, 2 caregivers, 11 health volunteers, and 2 community health workers. The participants were appointed for group and individual face-to-face in-depth interviews through semi-structured questions that lasted approximately 1 hour. An interview guide was developed based on the study objectives and relevant research literature, such as "How do older adults live in the community?" This was done until the data were saturated when there was no new information. Interviews were digitally recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. After completing each interview, the researcher promptly began writing basic field notes to document the participants' behaviors, facial expressions, and the surrounding environment. This was done to ensure that the information gathered was comprehensive and complete. Data collection took place at Ban Ta-Muang subdistrict health-promoting hospitals. All researchers had experience in conducting qualitative research.

Step 2: Development of a training program for homebound and bedridden older adults

The researchers wrote a draft of a training program based on the information and data from step 1. The content of the training program comprised of 2 sessions. First, the participants attended a 2-day (16-hour) theoretical training session held at Thamuangwittayakom School by a nutritionist, physical therapist, and community nurse practitioner. Second, the participants underwent practical training sessions on a weekly basis for a period of 12 weeks in Tha-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand. The theoretical training session consisted of 2 activities: 1) providing knowledge about caring for older adults to educate and support youth (youth were trained to increase their knowledge about physiological changes, nutrition, exercise, hygiene [especially oral care], and mental care to reduce stress) and 2) demonstrating and practicing in caring for older adults to educate and support youth (youth were trained and practiced on basic care for older adults, including shampooing, nail clipping, and primary health screening [such as blood pressure and body temperature monitoring]). Importantly, youth were also trained in communication skills for interacting with older adults who may have age-related deterioration, such as deafness. The practical training session consisted of 4 activities. 1) Caring for older adults with love and care: Youth practiced providing care to older adults in the community on a weekly basis for 12 weeks). They engaged in meaningful conversations, read fairy tales and books, participated in worship activities, offered massages for relaxation, and dedicated their time to being a compassionate friend and listener for older adults, ensuring they never felt lonely. 2) Providing hygiene care to older adults: Youth practiced providing basic care for older adults, including shampooing, nail clipping, and monitoring blood pressure and body temperature. 3) Promoting self-worth and self-confidence in youth: After providing health care to older adults, youth reflected on their own strengths and areas that needed development. Following 12 weeks of providing health care, they presented and contested innovations for promoting an aging-friendly environment, such as a mobile toilet, coconut wood for exercise, and an accident prevention chair. This experience helped youth feel more self-worth and self-confidence in taking care of older adults in their community. 4) Enhancing community participation: The community participation included representatives from local government organizations, community leaders, older adults from elderly clubs, caregivers, health volunteers, community health workers, teachers, and students involved in the development of this program. The President of the Subdistrict Administrative Organization supported youth in expressing their innovative ideas through a contest and presentation. The process of training program was divided into 3 steps: 1) pre-assessment, 2) implementation, and 3) evaluation. To assess the effectiveness of this training program, the researchers developed an evaluation questionnaire. They then shared both model development and the evaluation form with 5 experts specializing in gerontological nursing, community health nursing, and research and development. The experts were requested to evaluate and approve the program based on their professional expertise. The feedback, comments, and suggestions provided by the experts were reviewed Figure 1, and they were implemented during step 3.

Step 3: Implementation and evaluation of the program

The duration of the training program was over a period of 12 weeks in Tha-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand. The training session was carried out by 51 young individuals and 11 health volunteers, all of whom had completed a 70-hour caregiver training program, for 51 homebound and bedridden elderly individuals using purposive sampling. However, by the tenth week, one of the bedridden individuals had to be admitted to the hospital. The researcher provided consultations to the health volunteers and youth at the study site as needed. As a result, 50 homebound and bedridden older adults participated in the evaluation. The research compared the quality of life and stress between homebound and bedridden older adults before and after the implementation of the program.

For quantitative data collection, first, the Thai version of the brief form of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF-THAI) was used tool (19). It consists of 26 items and is based on a 5-point Likert scale, having 4 subscales measuring physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and satisfaction with the environment. In terms of interpretation, the mean scores are categorized into 3 levels. A mean score ranging from 96 to 130 indicates a good level of quality of life, while a score between 61 and 95 represents an average level. Mean scores falling between 26 and 60 indicate a relatively lower quality of life. Then, the Srithanya Stress Test (ST-5) of the Thai Department of Mental Health, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, was used (20). The test consists of 5 items that evaluate issues related to sleep, concentration, anxiety, boredom, and isolation. These items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). The interpretation of stress levels was categorized into 4 groups based on the scores obtained: no stress (scores ranging from 0 to 4), mild stress (scores ranging from 5 to 7), moderate stress (scores ranging from 8 to 9), and severe stress (scores <10) (20). Data was analyzed using percentages and means for demographic data. Questionnaires were analyzed using means, SDs, and paired t tests.

The instruments were tested for content validity by 3 experts (2 gerontology nurses and 1 community nurse). The implementation of the WHOQOL-BREE-THAI questionnaire and stress test had a scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) of 0.92 and 0.94, respectively; in addition, internal consistency reliability was tested through a pilot study among 30 older adults in Koh Kaew Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, who had similar qualifications to the actual participants and yielded the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.80 and 0.89, respectively.

The tools for qualitative data collection were focus group discussions and in-depth interviews through semi-structured questions to analyze the community context. Data were analyzed using a content analysis method (21). The transcripts from participants were read line-by-line. Then, codes were generated. Similar codes were grouped into subthemes and themes, respectively. This analysis was performed manually.

Trustworthiness is important to increase confidence that the study findings reflect the participants’ perspectives (22). The strategies used to enhance the trustworthiness of the study findings are as follows: 1) credibility: the researchers-built relationships with all participants to build trust to achieve the accuracy of the data. The research finding was shared and re-checked with the research team. Interpretation of research data was ascertained between the participants and researchers. Furthermore, the analyzed findings were proved by 3 experts who were gerontological nursing teachers and had experience in conducting qualitative research; in addition, their findings were expressed in a peer debriefing. Some minor suggestions made the findings more complete after revision; (2) transferability: the researchers carefully completed the findings by analyzing the information and including all data; (3) dependability: the researchers clearly described the research process from the beginning to the reporting phase. Research tools, methodology, and findings are relevant. The researchers used several tools to collect data (such as a voice recorder, demographic data, and field note record forms) to ensure the thorough and accurate collection and recording of all relevant data; and (4) conformability: at every stage of this study, clear data and evidence were analyzed, which can be authenticated; in addition, the researchers meticulously followed the qualitative research steps throughout the study.

Results

The results of this study can be summarized into qualitative and quantitative results.

Qualitative results

Twenty participants (aged 42 to 74 years) were interviewed, comprising 8 males and 12 females. Among them, 12 had a primary school education, while 8 were high school graduates or had attained a higher level of education.

The findings on the current situations and health care needs among homebound and bedridden older adults showed 3 major themes.

Theme 1: Lack of caregivers

Many older adults in this community lived with their grandchildren or youth because their own children worked in the capital. Some older adults suffer from underlying health conditions and cannot take care of themselves due to the lack of caregivers.

In this regard, participant 2 expressed, “…I lived with my grandchildren. Sometimes, I felt leg pain and could not walk. So, I needed my grandchildren to help me with bathing.” Participant 5 mentioned, “…I have no one. I lived alone. Sometimes, I forget to take the medicine that makes me feel a headache….”. Participant 2 said, “…I had trouble holding my urine. I had to crawl to the toilet by myself.”

Theme 2: Lack of knowledge

Subtheme 1: Older adults lack knowledge in caring themselves

Some older adults did not know how to care for themselves with underlying health conditions. They did not know how to exercise to maintain physical fitness.

Participant 15 exemplified this lack of knowledge by stating, “…Some older adult had hypertension and dyslipidemia, she still loved to eat fermented fish sauce and drink coffee every day that contains high cream and sugar.”

Participant 19 added, “…My grandmother said that she could not exercise due to her advanced age.”

Subtheme 2: Youth lack knowledge in caring for older adults

Most of the youth did not understand physical and mental changes during the aging period. They did not have the knowledge and skill to take care of homebound and bedridden older adults. They actually wanted to care, but they just did not know.

Participant 18 shared an example, stating, “…I observe my niece. She wanted to help me to provide passive exercise to prevent joint stiffness in my bedridden mother. She just did not want to do it because she worried that she would hurt my mother. She did not know how to take care of my bedridden mother….”.

Participant 15 highlighted another aspect of the youth's lack of knowledge, explaining, “…Youth did not understand why they had to speak slowly and louder while talking to older adults. They spoke too fast; sometimes, older adults did not understand and felt bad.”

Theme 3: Loneliness and stress

Some older adults lived alone because some of their own children were deceased or divorced and worked in the capital. Older adults feel lonely because they have no one to talk with. Some older adults feel stress with their financial problem and their physical illness, which could result in mental illness.

Participant 13 expressed the sense of loneliness among older adults, stating, “…Older adults felt lonely because they could not go out to the temple in the morning as usual due to leg weakness....”. Participant 15 mentioned the stress experienced by older adults, explaining, “…Older adults sometimes feel stress when they do not have enough money to use.”

Theme 4: Under the poverty line

Most older adults are under the poverty line and struggling to make ends meet. Participant 7 expressed the financial struggles of older adults, stating, “…It is not enough for me, although older adults received money from older adults’ allowances (700 Baht). It was still not enough for them and their grandchildren to live on….”.

Participant 16 shared a similar experience, mentioning, “…My son worked in the capital to earn money. Some months, he did not transfer money because he needed to support his family....”.

Quantitative results

The participants consisted of 51 homebound and bedridden older adults. The age range was between 60 and 80+ years; most of them were aged between 70 to 79 years (50%). The majority were female (74%). Most of them lived with descendants (52%). The majority had underlying diseases (76%), and all of them were Buddhist (100%).

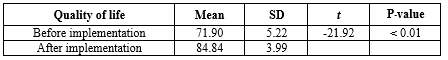

Findings on the implementation of the training program among homebound and bedridden older adults using peer support from health volunteers to educate and support youth are as follows: Firstly, the median after the implementation of the model was found to be significantly higher than before the implementation, with quality-of-life score of 0.01 as shown in Table 1.

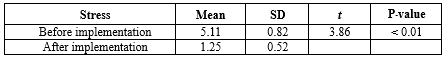

Secondly, the program implementation of stress among homebound and bedridden older adults had significantly lower mean scores compared to prior implementation, as shown in Table 2.

Discussion

In the current study, most homebound and bedridden older adults lived with their descendants who were youth. This is often because their parents worked in the capital, had died, or divorced. Some older adults lived alone or with a spouse. Unfortunately, caregivers for these older adults are often youth or older adults themselves and lack knowledge of proper care. As a result, older adults were stressed and had a moderate level of quality of life. Similarly, loneliness and social isolation were prospectively associated with decreased quality of life among older adults (23). According to a study, older adults living alone are vulnerable in terms of their physical and mental health. This group faces specific public health and service needs that should be addressed to support their well-being (24). This study found that most of the older adults had poor economic status. A previous study showed that poverty and health-related quality of life (25), especially poverty, had a significant negative impact on mental health (26). Therefore, the researcher developed a training program for caring for homebound and bedridden older adults through community participation to enhance their quality of life.

The results of this study showed that youth residing in the community lacked the necessary knowledge and skills to provide health care to homebound and bedridden older adults. Accordingly, the researchers developed a training program to address this gap and enhance the abilities of youth in providing proper care for this vulnerable population. According to the existing literature, intergenerational programs have demonstrated the potential to have a positive impact on youth, fostering more positive attitudes and knowledge about the physical and mental changes that accompany the aging process. These programs aim to enhance the quality of life for older adults (27,28). Similarly, youth are needed to provide awareness programs regarding changes that occur during aging, contributing to the overall quality of life for older adults (29,30). Our results also showed that the training program carried out by youth with the help of health volunteers resulted in higher mean scores of qualities of life and lower mean scores of stresses. This may be attributed to the fact that the majority of youth involved in providing health care in this study were grandchildren who lived within the same community as the older adults. Importantly, older adults could reduce stress and improve their quality of life after implementing the training program (31). This is consistent with (32), who stated that structured teaching programs had a positive effect on the level of stress among older adults.

The availability of geriatric resources and trained personnel across the continuum of care is critical to the successful implementation and sustainment of these innovative models of care for older adults that have been found to be successful in many varied health care systems worldwide (33). However, this program was developed in local areas with the involvement of stakeholders and has led to an enhanced quality of life for older adults. To effectively address these needs, it is important to understand the care and support needs of older adults (34). Importantly, community participation was the key to developing a training program for homebound and bedridden older adults in Ta-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand. This approach allowed stakeholders to freely express their opinions and develop a practical and efficient model based on the circumstances of the area. As a result, the program developed was successful in taking care of the health of homebound and bedridden older adults. For future community care designs for older adults, involving community participation in decision-making is recommended to ensure continuous and sustainable care. As the population ages and health care demands increase, community participation has become an important factor for healthy aging (35). Moreover, this training program involved community participation in every step of the research study.

Since Thai society is a caring society, people in communities help to take care of each other, but they still lack knowledge of appropriate health care. Therefore, to address this need, the researchers organized a group of individuals from the community who live at home with older adults to actively participate in this project. Furthermore, the researcher and the nursing lecturers at the Faculty of Nursing at Roi Et Rajabhat University are responsible for developing local communities by integrating knowledge into innovation in local development to create national stability as a vision of the university, which is necessary to enhance the quality of life of people, including older adults.

This study has some limitations. First, the results of this study were specific to the context of Ta-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand. The findings of this study can be referenced and applied to other communities with similar contexts, unless further adjustments and evaluations of implementation are required. Second, the young caregivers in this study had slightly different ages, resulting in different perceptions and practice training. Third, this research used a quasi-experimental design (1 group and a pretest-posttest design) in step 3. The intervention implemented in this study has the potential to be effective in enhancing the quality of life and reducing stress among homebound and bedridden older adults by providing a new experience for homebound and bedridden older adults. Therefore, the pretest-posttest design with a comparison group is recommended.

Conclusion

Thai society is a caring society. People in communities help to take care of each other, but they still lack knowledge of appropriate health care. This training program could promote bonding among the youth and homebound and bedridden older adults using peer support from health volunteers. Additionally, youth had the potential to take care of homebound and bedridden older adults. This community participation in caring for older adults could create strength and sustainability for people in the community to take care of themselves to enhance their quality of life. Thus, this model could be used in other communities with similar contexts.

Acknowledgement

We greatly appreciate all the participants in this study for their wonderful cooperation. This study was supported by the Faculty of Nursing, Roi Et Rajabhat University, Roi Et, Thailand.

Funding sources

This study was funded and supported by the Faculty of Nursing, Roi Et Rajabhat University, Roi Et, Thailand (Grant No. special/2563).

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Roi Et Rajabhat University, Thailand (certification No. 016/2563). Additionally, the researchers informed eligible participants of their right to voluntarily participate, withdraw at any time, maintain confidentiality, and protect their privacy. Participants who agreed to participate were asked to sign a consent form. To maintain anonymity, all participants were instructed not to include their names or any other identifying information on the questionnaires.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed significantly to this study. B.W., Ch.S., L.Ph., and N.Ph. performed the research design, data collection, and data analysis. Ch.S. and N.Ph supervised the execution of the study and data collection. B.W. and L.Ph wrote the manuscript. All the authors approved the content of the manuscript.

The number and proportion of people aged 60 years or older is rapidly increasing worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, there were 1 billion people aged 60 or older in 2019. The number of older adults is expected to increase to 1.4 billion by 2030 and 2.1 billion by 2050 (1). An increase in the older adult population in Thailand has increased the proportion of homebound and bedridden older adults. As the aging population rapidly grows and rates of chronic diseases increase, caring for them poses many challenges to both the government and families (2,3). In addition, the number of homebound and bedridden individuals is expected to be 321,511 and 152,749, respectively, by 2030. The number of bedridden older adults will reach 153,000 in the next decade (4). Meanwhile, the current global demographic situation is characterized by an increase in average life expectancy and a low birth rate, as well as a growing number of older adults (5).

At the same time, older adults live longer. They are facing the deterioration of physical and psychological health. Older adults are more likely to suffer from chronic conditions and multi-morbidities, and their functional capacity is frequently limited (6). Importantly, older adults can stress on their health related to quality of life (7). Homebound and bedridden older adults need health care from health care providers and family members, as well as community participation, to improve their health. Health care is important to slow down deterioration, reduce chronic illness, reduce expenses caused by illness, and increase the level of activities of daily living by enabling older adults to live happily, resulting in a good quality of life (6, 8, 9). Being homebound and bedridden can affect older adults’ physical and mental health by decreasing movement, which can itself be exacerbated by the deterioration of older adults’ health.(10,11) As a result, older adults will age in their own homes, and the majority of them have one or more chronic disorders, depression, and stress (12-14). Thus, health problems can affect the quality of life among homebound and bedridden older adults (11).

With the changing trend of population structure in Thai society, as economic and demographic changes occur, family size is getting smaller; in addition, approximately one-third of the older adults are under the poverty line. Conversely, there is a growing population of elderly individuals who are homebound or bedridden, facing financial insecurity, while the availability of family caregivers is decreasing (3). Some older adults who live alone are vulnerable physically, emotionally, and socially (15). Spouses and children constitute approximately 90% of the main caregivers for older adults. Thus, informal caregivers play a significant role in caring for older adults. On the other hand, their knowledge, practice, and needs in older adults caring are weak and poorly characterized (16,17). However, the Thai government has put considerably more effort into establishing and developing long-term care policies to provide home care and social support for homebound and bedridden older adults. The health volunteers and elderly home care volunteers will work closely together with subdistrict health-promoting hospitals or local governments to provide essential medical and social support to older adults with disabilities in their communities (3). Nevertheless, the number of caregivers is still insufficient; thus, young individuals in the community are another important group that should provide health care for homebound and bedridden older adults.

In rural northeastern Thai society, young individuals are descendants of older adults in the community who want to take care of their fathers, mothers, grandfathers, and grandmothers both in the present and future. In addition, according to the myth of a uniquely caring Thai society, they need to further participate with the community to take care of older adults in their community. The program aims to enhance knowledge, cultivate essential caregiving skills for homebound and bedridden older adults, foster a positive mindset in young individuals, and establish an elderly-friendly environment through the support of health volunteers. Ultimately, this leads to an improved quality of life for homebound and bedridden older adults. Consequently, the researchers were interested in conducting research. This study hypothesized that the participation of homebound and bedridden older adults in the training program could enhance their quality of life and reduce stress. This study aimed to develop a program for homebound and bedridden older adults using peer support from health volunteers to educate and support youth in Tha-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand.

Methods

Design

This study is part of a larger research and development project conducted from February to June 2020, employing mixed methods research. The project was conducted in 3 steps as follows: 1) exploration of the current situation using a qualitative method, 2) development of a training program, and 3) implementation and evaluation of a program developed through a quasi-experimental method. The detailed results regarding the involvement of youth in step 3 were published in a nursing journal in Thailand (18). The current paper presents only the issue among homebound and bedridden older adults.

Step 1: Exploration of the current situation among homebound and bedridden older adults

The researcher investigated several documents and studies concerning concepts and theories related to health care among homebound and bedridden older adults. Based on the literature review, in-depth interviews and focus group discussions were used to analyze the community context and the need for health care among homebound and bedridden older adults. The participants were 20 stakeholders, consisting of 1 local government organization, 2 community leaders, 2 older adults from elderly clubs, 2 caregivers, 11 health volunteers, and 2 community health workers. The participants were appointed for group and individual face-to-face in-depth interviews through semi-structured questions that lasted approximately 1 hour. An interview guide was developed based on the study objectives and relevant research literature, such as "How do older adults live in the community?" This was done until the data were saturated when there was no new information. Interviews were digitally recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. After completing each interview, the researcher promptly began writing basic field notes to document the participants' behaviors, facial expressions, and the surrounding environment. This was done to ensure that the information gathered was comprehensive and complete. Data collection took place at Ban Ta-Muang subdistrict health-promoting hospitals. All researchers had experience in conducting qualitative research.

Step 2: Development of a training program for homebound and bedridden older adults

The researchers wrote a draft of a training program based on the information and data from step 1. The content of the training program comprised of 2 sessions. First, the participants attended a 2-day (16-hour) theoretical training session held at Thamuangwittayakom School by a nutritionist, physical therapist, and community nurse practitioner. Second, the participants underwent practical training sessions on a weekly basis for a period of 12 weeks in Tha-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand. The theoretical training session consisted of 2 activities: 1) providing knowledge about caring for older adults to educate and support youth (youth were trained to increase their knowledge about physiological changes, nutrition, exercise, hygiene [especially oral care], and mental care to reduce stress) and 2) demonstrating and practicing in caring for older adults to educate and support youth (youth were trained and practiced on basic care for older adults, including shampooing, nail clipping, and primary health screening [such as blood pressure and body temperature monitoring]). Importantly, youth were also trained in communication skills for interacting with older adults who may have age-related deterioration, such as deafness. The practical training session consisted of 4 activities. 1) Caring for older adults with love and care: Youth practiced providing care to older adults in the community on a weekly basis for 12 weeks). They engaged in meaningful conversations, read fairy tales and books, participated in worship activities, offered massages for relaxation, and dedicated their time to being a compassionate friend and listener for older adults, ensuring they never felt lonely. 2) Providing hygiene care to older adults: Youth practiced providing basic care for older adults, including shampooing, nail clipping, and monitoring blood pressure and body temperature. 3) Promoting self-worth and self-confidence in youth: After providing health care to older adults, youth reflected on their own strengths and areas that needed development. Following 12 weeks of providing health care, they presented and contested innovations for promoting an aging-friendly environment, such as a mobile toilet, coconut wood for exercise, and an accident prevention chair. This experience helped youth feel more self-worth and self-confidence in taking care of older adults in their community. 4) Enhancing community participation: The community participation included representatives from local government organizations, community leaders, older adults from elderly clubs, caregivers, health volunteers, community health workers, teachers, and students involved in the development of this program. The President of the Subdistrict Administrative Organization supported youth in expressing their innovative ideas through a contest and presentation. The process of training program was divided into 3 steps: 1) pre-assessment, 2) implementation, and 3) evaluation. To assess the effectiveness of this training program, the researchers developed an evaluation questionnaire. They then shared both model development and the evaluation form with 5 experts specializing in gerontological nursing, community health nursing, and research and development. The experts were requested to evaluate and approve the program based on their professional expertise. The feedback, comments, and suggestions provided by the experts were reviewed Figure 1, and they were implemented during step 3.

Step 3: Implementation and evaluation of the program

The duration of the training program was over a period of 12 weeks in Tha-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand. The training session was carried out by 51 young individuals and 11 health volunteers, all of whom had completed a 70-hour caregiver training program, for 51 homebound and bedridden elderly individuals using purposive sampling. However, by the tenth week, one of the bedridden individuals had to be admitted to the hospital. The researcher provided consultations to the health volunteers and youth at the study site as needed. As a result, 50 homebound and bedridden older adults participated in the evaluation. The research compared the quality of life and stress between homebound and bedridden older adults before and after the implementation of the program.

For quantitative data collection, first, the Thai version of the brief form of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF-THAI) was used tool (19). It consists of 26 items and is based on a 5-point Likert scale, having 4 subscales measuring physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and satisfaction with the environment. In terms of interpretation, the mean scores are categorized into 3 levels. A mean score ranging from 96 to 130 indicates a good level of quality of life, while a score between 61 and 95 represents an average level. Mean scores falling between 26 and 60 indicate a relatively lower quality of life. Then, the Srithanya Stress Test (ST-5) of the Thai Department of Mental Health, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, was used (20). The test consists of 5 items that evaluate issues related to sleep, concentration, anxiety, boredom, and isolation. These items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). The interpretation of stress levels was categorized into 4 groups based on the scores obtained: no stress (scores ranging from 0 to 4), mild stress (scores ranging from 5 to 7), moderate stress (scores ranging from 8 to 9), and severe stress (scores <10) (20). Data was analyzed using percentages and means for demographic data. Questionnaires were analyzed using means, SDs, and paired t tests.

The instruments were tested for content validity by 3 experts (2 gerontology nurses and 1 community nurse). The implementation of the WHOQOL-BREE-THAI questionnaire and stress test had a scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) of 0.92 and 0.94, respectively; in addition, internal consistency reliability was tested through a pilot study among 30 older adults in Koh Kaew Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, who had similar qualifications to the actual participants and yielded the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.80 and 0.89, respectively.

The tools for qualitative data collection were focus group discussions and in-depth interviews through semi-structured questions to analyze the community context. Data were analyzed using a content analysis method (21). The transcripts from participants were read line-by-line. Then, codes were generated. Similar codes were grouped into subthemes and themes, respectively. This analysis was performed manually.

Trustworthiness is important to increase confidence that the study findings reflect the participants’ perspectives (22). The strategies used to enhance the trustworthiness of the study findings are as follows: 1) credibility: the researchers-built relationships with all participants to build trust to achieve the accuracy of the data. The research finding was shared and re-checked with the research team. Interpretation of research data was ascertained between the participants and researchers. Furthermore, the analyzed findings were proved by 3 experts who were gerontological nursing teachers and had experience in conducting qualitative research; in addition, their findings were expressed in a peer debriefing. Some minor suggestions made the findings more complete after revision; (2) transferability: the researchers carefully completed the findings by analyzing the information and including all data; (3) dependability: the researchers clearly described the research process from the beginning to the reporting phase. Research tools, methodology, and findings are relevant. The researchers used several tools to collect data (such as a voice recorder, demographic data, and field note record forms) to ensure the thorough and accurate collection and recording of all relevant data; and (4) conformability: at every stage of this study, clear data and evidence were analyzed, which can be authenticated; in addition, the researchers meticulously followed the qualitative research steps throughout the study.

Results

The results of this study can be summarized into qualitative and quantitative results.

Qualitative results

Twenty participants (aged 42 to 74 years) were interviewed, comprising 8 males and 12 females. Among them, 12 had a primary school education, while 8 were high school graduates or had attained a higher level of education.

The findings on the current situations and health care needs among homebound and bedridden older adults showed 3 major themes.

Theme 1: Lack of caregivers

Many older adults in this community lived with their grandchildren or youth because their own children worked in the capital. Some older adults suffer from underlying health conditions and cannot take care of themselves due to the lack of caregivers.

In this regard, participant 2 expressed, “…I lived with my grandchildren. Sometimes, I felt leg pain and could not walk. So, I needed my grandchildren to help me with bathing.” Participant 5 mentioned, “…I have no one. I lived alone. Sometimes, I forget to take the medicine that makes me feel a headache….”. Participant 2 said, “…I had trouble holding my urine. I had to crawl to the toilet by myself.”

Theme 2: Lack of knowledge

Subtheme 1: Older adults lack knowledge in caring themselves

Some older adults did not know how to care for themselves with underlying health conditions. They did not know how to exercise to maintain physical fitness.

Participant 15 exemplified this lack of knowledge by stating, “…Some older adult had hypertension and dyslipidemia, she still loved to eat fermented fish sauce and drink coffee every day that contains high cream and sugar.”

Participant 19 added, “…My grandmother said that she could not exercise due to her advanced age.”

Subtheme 2: Youth lack knowledge in caring for older adults

Most of the youth did not understand physical and mental changes during the aging period. They did not have the knowledge and skill to take care of homebound and bedridden older adults. They actually wanted to care, but they just did not know.

Participant 18 shared an example, stating, “…I observe my niece. She wanted to help me to provide passive exercise to prevent joint stiffness in my bedridden mother. She just did not want to do it because she worried that she would hurt my mother. She did not know how to take care of my bedridden mother….”.

Participant 15 highlighted another aspect of the youth's lack of knowledge, explaining, “…Youth did not understand why they had to speak slowly and louder while talking to older adults. They spoke too fast; sometimes, older adults did not understand and felt bad.”

Theme 3: Loneliness and stress

Some older adults lived alone because some of their own children were deceased or divorced and worked in the capital. Older adults feel lonely because they have no one to talk with. Some older adults feel stress with their financial problem and their physical illness, which could result in mental illness.

Participant 13 expressed the sense of loneliness among older adults, stating, “…Older adults felt lonely because they could not go out to the temple in the morning as usual due to leg weakness....”. Participant 15 mentioned the stress experienced by older adults, explaining, “…Older adults sometimes feel stress when they do not have enough money to use.”

Theme 4: Under the poverty line

Most older adults are under the poverty line and struggling to make ends meet. Participant 7 expressed the financial struggles of older adults, stating, “…It is not enough for me, although older adults received money from older adults’ allowances (700 Baht). It was still not enough for them and their grandchildren to live on….”.

Participant 16 shared a similar experience, mentioning, “…My son worked in the capital to earn money. Some months, he did not transfer money because he needed to support his family....”.

Quantitative results

The participants consisted of 51 homebound and bedridden older adults. The age range was between 60 and 80+ years; most of them were aged between 70 to 79 years (50%). The majority were female (74%). Most of them lived with descendants (52%). The majority had underlying diseases (76%), and all of them were Buddhist (100%).

Findings on the implementation of the training program among homebound and bedridden older adults using peer support from health volunteers to educate and support youth are as follows: Firstly, the median after the implementation of the model was found to be significantly higher than before the implementation, with quality-of-life score of 0.01 as shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1. The comparison of quality of life between homebound and bedridden older adults before and after the implementation of the training program

|

|

Table 2. The comparison of mean stress between homebound and bedridden older adults before and after the implementation

|

Discussion

In the current study, most homebound and bedridden older adults lived with their descendants who were youth. This is often because their parents worked in the capital, had died, or divorced. Some older adults lived alone or with a spouse. Unfortunately, caregivers for these older adults are often youth or older adults themselves and lack knowledge of proper care. As a result, older adults were stressed and had a moderate level of quality of life. Similarly, loneliness and social isolation were prospectively associated with decreased quality of life among older adults (23). According to a study, older adults living alone are vulnerable in terms of their physical and mental health. This group faces specific public health and service needs that should be addressed to support their well-being (24). This study found that most of the older adults had poor economic status. A previous study showed that poverty and health-related quality of life (25), especially poverty, had a significant negative impact on mental health (26). Therefore, the researcher developed a training program for caring for homebound and bedridden older adults through community participation to enhance their quality of life.

The results of this study showed that youth residing in the community lacked the necessary knowledge and skills to provide health care to homebound and bedridden older adults. Accordingly, the researchers developed a training program to address this gap and enhance the abilities of youth in providing proper care for this vulnerable population. According to the existing literature, intergenerational programs have demonstrated the potential to have a positive impact on youth, fostering more positive attitudes and knowledge about the physical and mental changes that accompany the aging process. These programs aim to enhance the quality of life for older adults (27,28). Similarly, youth are needed to provide awareness programs regarding changes that occur during aging, contributing to the overall quality of life for older adults (29,30). Our results also showed that the training program carried out by youth with the help of health volunteers resulted in higher mean scores of qualities of life and lower mean scores of stresses. This may be attributed to the fact that the majority of youth involved in providing health care in this study were grandchildren who lived within the same community as the older adults. Importantly, older adults could reduce stress and improve their quality of life after implementing the training program (31). This is consistent with (32), who stated that structured teaching programs had a positive effect on the level of stress among older adults.

The availability of geriatric resources and trained personnel across the continuum of care is critical to the successful implementation and sustainment of these innovative models of care for older adults that have been found to be successful in many varied health care systems worldwide (33). However, this program was developed in local areas with the involvement of stakeholders and has led to an enhanced quality of life for older adults. To effectively address these needs, it is important to understand the care and support needs of older adults (34). Importantly, community participation was the key to developing a training program for homebound and bedridden older adults in Ta-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand. This approach allowed stakeholders to freely express their opinions and develop a practical and efficient model based on the circumstances of the area. As a result, the program developed was successful in taking care of the health of homebound and bedridden older adults. For future community care designs for older adults, involving community participation in decision-making is recommended to ensure continuous and sustainable care. As the population ages and health care demands increase, community participation has become an important factor for healthy aging (35). Moreover, this training program involved community participation in every step of the research study.

Since Thai society is a caring society, people in communities help to take care of each other, but they still lack knowledge of appropriate health care. Therefore, to address this need, the researchers organized a group of individuals from the community who live at home with older adults to actively participate in this project. Furthermore, the researcher and the nursing lecturers at the Faculty of Nursing at Roi Et Rajabhat University are responsible for developing local communities by integrating knowledge into innovation in local development to create national stability as a vision of the university, which is necessary to enhance the quality of life of people, including older adults.

This study has some limitations. First, the results of this study were specific to the context of Ta-Muang Subdistrict, Selaphum District, Roi Et Province, Thailand. The findings of this study can be referenced and applied to other communities with similar contexts, unless further adjustments and evaluations of implementation are required. Second, the young caregivers in this study had slightly different ages, resulting in different perceptions and practice training. Third, this research used a quasi-experimental design (1 group and a pretest-posttest design) in step 3. The intervention implemented in this study has the potential to be effective in enhancing the quality of life and reducing stress among homebound and bedridden older adults by providing a new experience for homebound and bedridden older adults. Therefore, the pretest-posttest design with a comparison group is recommended.

Conclusion

Thai society is a caring society. People in communities help to take care of each other, but they still lack knowledge of appropriate health care. This training program could promote bonding among the youth and homebound and bedridden older adults using peer support from health volunteers. Additionally, youth had the potential to take care of homebound and bedridden older adults. This community participation in caring for older adults could create strength and sustainability for people in the community to take care of themselves to enhance their quality of life. Thus, this model could be used in other communities with similar contexts.

Acknowledgement

We greatly appreciate all the participants in this study for their wonderful cooperation. This study was supported by the Faculty of Nursing, Roi Et Rajabhat University, Roi Et, Thailand.

Funding sources

This study was funded and supported by the Faculty of Nursing, Roi Et Rajabhat University, Roi Et, Thailand (Grant No. special/2563).

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Roi Et Rajabhat University, Thailand (certification No. 016/2563). Additionally, the researchers informed eligible participants of their right to voluntarily participate, withdraw at any time, maintain confidentiality, and protect their privacy. Participants who agreed to participate were asked to sign a consent form. To maintain anonymity, all participants were instructed not to include their names or any other identifying information on the questionnaires.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed significantly to this study. B.W., Ch.S., L.Ph., and N.Ph. performed the research design, data collection, and data analysis. Ch.S. and N.Ph supervised the execution of the study and data collection. B.W. and L.Ph wrote the manuscript. All the authors approved the content of the manuscript.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Management and Health System

References

1. World health organization. Ageing and health [internet]. 2022. [View at Publisher]

2. Wicha S, Saovapha B, Sripattarangkul S, Manop N, Muankonkaew T, Srirungrueang S. Health status of dependent older people and pattern of care among caregivers: a case study of Hong ha health promoting hospital, Lampang, Thailand. Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research 2018;5(3): 228-49. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

3. Suriyanrattakorn S, Chang CL. Long-term care (LTC) policy in Thailand on the homebound and bedridden elderly happiness. Health Policy Open. 2021;2:100026. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Tantirat P, Suphanchaimat R, Rattanathumsakul T, Noree T. Projection of the number of elderly in different health states in Thailand in the next ten years, 2020-2030. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22): 8703. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Khavinson V, Popovich I, Mikhaiova O. Towards realization of longer life. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(3): e2020054. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Golinowska S, Groot W, Baji P, Pavlova M. Health promotion targeting older people. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16 Suppl 5(Supple5):367-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Frias deMC, Whyne E. Stress on health-related quality of life in older adults: the protective nature of mindfulness. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(3):201-6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Hsu HI, Liu CC, Yang FS, Chen HC. A health promotion program for older adults (KABAN!): effects on health literacy, quality of life, and emotions. Educational Gerontology. 2023;49(8):639-56. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

9. Miller CA. Nursing for wellness in older adult. 8th ed. Philadephia: Wolters Kluwer; 2021. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

10. Ko Y, Noh W. A scoping review of homebound older people: definition, measurement and determinants. Int J Environ Res Public health. 2021;18(8):3949. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Normala R, Lukman ZM. Bedridden Elderly: factors and risks. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation. 2020;7(8):46-9. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

12. Leeuwen VKM, Loon M, van Nes FA, Bosmans JE, Vet HCW, Ket JCF, et al. What does quality of life mean to older adults? A thematic synthesis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0213263 [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Dao TMA, Nguyen VT, Nguyen HV, Nguyen LTK. Factors associated with depression among the elderly living in urban Vietnam. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018: 2370284. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Amestoy ME, D'Amico D, Fiocco AJ. Neuroticism and Stress in Older Adults: The buffering Role of self-esteem. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(12):6102. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. Cheong CY, Ha NH, Choo RW, Yap PL. Will teenagers today live with and care for their aged parents tomorrow? Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018:18(6):957-64. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Knodel J, Teerawichitchainan B, Pothisiri W. Caring for Thai older persons with long-term care needs. J Aging Health. 2018;30(10): 1516-35. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

17. Ab Ghani NN, Makhtar A, Syed Elias SM, Ahmad N, Ludin SM. Knowledge, practice and need of family caregiver in the care of older people: A review. International journal of care scholars. 2022;5(3):70-8. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

18. Wongpimoln B, Pholputta P, Sayuen C, Injumpa C, Wannapuek P, Phengphol N. Effectiveness of an education program for youth in providing care for elderly people in Tha-Muang Subdistrict Community, Selaphum District, Roi Et province. TRC Nurs J. 2022;15(1):177-89. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

19. Mahatnirundkul S. Comparison of the WHOQOL-100 and the WHOQOL-BREF (26 items). J Ment Health Thai. 1998;5:4-15. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

20. Silpakit O. Srithanya stress scale. Journal of Mental Health of Thailand. 2008;16(3):177-85. (in Thai). [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

21. Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 2010. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

22. Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research. Sage;1994. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

23. Beridze G, Ayala A, Ribeiro O, Fernández-Mayoralas G, Rodríguez-Blázquez C, Rodríguez-Rodríguez V, et al. Are Loneliness and Social Isolation Associated with Quality of Life in Older Adults? Insights from Northern and Southern. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8637. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

24. Iamtrakul P, Chayphong S. Exploring the influencing factors on living alone and social isolation among older adults in rural areas of Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):14572. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

25. Li Z, Zhang L. Poverty and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study in rural China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):153. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Li Y, Chen T, Li Q, Jiang L. The Impact of Subjective Poverty on the Mental Health of the Elderly in China: The Mediating Role of Social Capital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(17):6672. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

27. Kim J, Lee J. Intergenerational program for nursing Home Residents and Adolescents in Korea. J Gerontol Nurs. 2018;44(1):32-41. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

28. Petersen J. A meta-analytic review of the effects of intergenerational programs for youth and older adults. Education gerontology. 2023;49(3):175-89. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

29. Cheong YC, HL Ha N, Choo RW, Yap P. Will teenagers today live with and care for their aged parents tomorrow?: Will teenagers care for parents tomorrow? Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(6):957-64. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

30. Gaire B, Khagi BR. Attitude of the youth towards the elderly people in the selected community in Lalitpur district of Nepal. J Nat Med College. 2020;5(1):46-53. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

31. Choowanthanapakorn M, Seangpraw K, Ongartborirak P. Effect of stress management training for elderly in rural northern Thailand. The Open Public Health Journal. 2021;14:62-70. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

32. Kumari Geetha S, Selvaraj P. Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Programme on Geriatric Stress among the Elderly Population. Int J Nurs Educ Res. 2022;10(1):11-5. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

33. Powers JS. Geriatric Care Models. Geriatrics (Basel). 2021;6(1): 6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

34. Abdi S, Spann A, Borilovic J, Witte DL, Hawley M. Understanding the care and support needs of older people: a scoping review and categorisation using the WHO international classification of functioning, disability and health framework (ICF). BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):1-5. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

35. Gough C, Lewis KL, Barr C, Maeder A, George S. Community participation of community dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1-13. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |