Volume 20, Issue 1 (4-2023)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2023, 20(1): 40-44 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hassankhani H, Haririan H, E Porter J, Oshni Alvandi A. “Paramedics are only a driver,” The lived experience of Iranian paramedics from patient handover: A qualitative study. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2023; 20 (1) :40-44

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1455-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1455-en.html

1- School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2- School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran ,houman.haririan@gmail.com

3- School of Nursing, Midwifery and Healthcare, Federation University Australia, Australia

4- Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Australia.

2- School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran ,

3- School of Nursing, Midwifery and Healthcare, Federation University Australia, Australia

4- Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Australia.

Full-Text [PDF 433 kb]

(1241 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2966 Views)

Full-Text: (765 Views)

Introduction

Patient handover in the emergency department (ED) is a 2-way communication process between the paramedics and in-hospital emergency personnel, which can result in miscommunication and delivery challenges (1). Pre-hospital emergency services play a crucial role in the health care system by transferring vital information about the patient to ED personnel, particularly in situations involving time-critical and urgent care. To improve the quality of patient care in the ED, focus should be placed on all stages of the communication delivery process, including how to transfer and hand over patients from the pre-hospital emergency setting to the in-hospital emergency personnel (2).

Patient handover refers to the process of transferring patient care information and responsibility from 1 care provider or team to another, which plays an important role in each patients’ clinical safety and harm minimization (3). In European countries, 25%-40% of unwanted adverse events occur during patient handover (4). According to the US Patient Safety Committee, an inappropriate patient handover, in which patient information is not fully transferred, accounts for 65% of the irreversible damage to patients. Some of the adverse events related to poor handover included delays in treatment or procedure, prolonged treatment or procedure (leading to patient deterioration), errors involving medications, lack of monitoring information given on clinical assessment, patient falls, and disruptive and aggressive behavior toward patients (5). A study investigated the clinical handover processes between Australian ambulance personnel and ED staff for patients arriving by ambulance, showing that the quality of handover is influenced by various factors, including the expectations of personnel, their prior experience, workload, and working relationships. However, issues such as a lack of active listening and limited access to written information were identified as contributing factors. This study also demonstrated the complexity of clinical handover from the ambulance service to the ED (6).

A voluntary reporting of adverse events in Iranian hospitals demonstrated that almost 7% of these events are caused by an inappropriate patient handover, highlighting the critical role of staff in completing accurate documentation and online reporting to prevent such incidents (7). Salehi et al (2016) conducted a study with the aim of identifying areas for improvement in patient handover, specifically focusing on the communication process between paramedics and ED nurses. The results of the study revealed that most miscommunication occurred due to a lack of knowledge regarding the relevant protocols, as well as communication challenges between triage nurses and paramedics during patient handover. These issues could potentially result in an increased number of adverse events for patients (3).

In road collisions in Iran, over 88.46% of injured patients are transported by ambulance to hospitals requiring a clinical handover (8). Jamshidi et al (2019) conducted a qualitative study with the aim of determining the challenges of cooperation between the pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency services in the handover of victims of road traffic accidents in Iran. Through purposive sampling, 15 employees from ambulance personnel and hospital emergency staff were interviewed, and they expressed their experiences of cooperation between these 2 teams in the handover of traffic accident casualties. The data analysis revealed 3 major challenges associated with ambulance patient handover: a shortage of infrastructure resources, inefficient and unscientific management, and non-common language (9). Moreover, little information is available on the experience of Iranian paramedics in patient handover to hospitals.

Given the importance of patient safety with a focus on the prevention of adverse events during handover and with the help of qualitative research to better identify unknown aspects of the phenomenon, this study aimed to explore the lived experience of paramedics during patient handover to ED personnel.

Methods

In this qualitative study, an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was used to identify the meaning of patient handover from the paramedics’ perspective in this study. The primary focus of IPA is the lived experience of participants and the meaning they make of this experience, but the end result is an interpretation of how the researcher thinks the participant is thinking. This analysis is an iterative process and involves moving between the part and the whole of the hermeneutic circle (10).

Participants were recruited using a purposeful sampling technique via Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in Tabriz City, Iran. As part of the inclusion criteria, participants who had the patient handover experience and expressed a willingness to participate in the study were invited, and there were no exclusion criteria based on age or ethnicity. Fifteen paramedics participated in this study over a period of 5 months (from November 2017 to April 2018). The sample size was determined according to the time when data richness was achieved. Data collection ended when the data was considered rich and varied enough to illuminate the phenomenon and when no new themes emerged. Variation within the data was enhanced by purposeful sampling and recruiting paramedics with work experience from less than 1 year to more than 16 years.

Participants were contacted via phone, face-to-face meetings, and emails. Semi-structured interviews (50-60 minutes) were conducted in the EMS stations or at a location and time preferred by the participants. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by the corresponding author. Demographic data were asked, followed by a series of interview guides exploring the participants’ experiences during the patient handover. Interview questions (interview guide) included “tell me your experiences regarding patient handover” and “what happened when you did patient handover.” Overall, 16 interview sessions were held with 16 participants. However, data richness was obtained after 15 interviews with no new emerging themes identified. Repeat interviews were not carried out.

Written consent was obtained from each participant prior to the interview, and fictitious and numerical names were assigned to maintain confidentiality. However, interviews conducted at the station may threaten anonymity; in this regard, the name and place of EMS stations did not mention in the text. The Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1395.296) approved this study.

A 6-step analysis process of the Smith, Flowers, and Larkin approach used as follows: 1) reading and re-reading, 2) initial noting, 3) developing emergent themes, 4) searching for connections across emergent themes, 5) moving to the next case, and 6) looking for patterns across cases. The themes included if stated by at least 3 or more participants (10). MAXQDA software (release 18.2.5) was used to manage data analysis.

The researcher used 4 criteria to ensure rigor and accuracy, including credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability, according to Lincoln and Guba (11). The interview transcripts were returned to the participants to ensure the accuracy of the codes and interpretations, increasing the credibility of the data. Participant checking did not result in any amendments, and participants felt they were accurate. An audit trail was used to control the dependability of the data, and an independent scrutiny of qualitative data and relevant documents by an external reviewer was obtained to evaluate the dependability of the data. However, the peer check approach was used to control data conformability. In addition, the authors’ detailed description ensured the transferability of the data (11).

Results

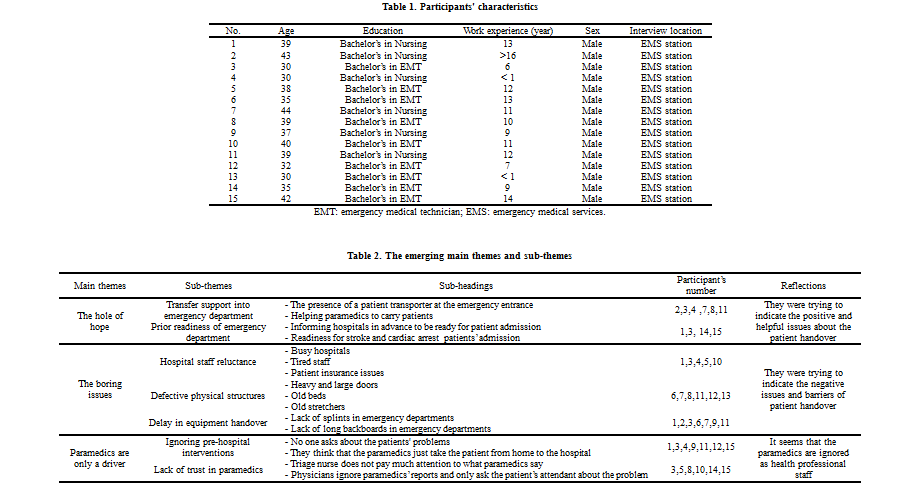

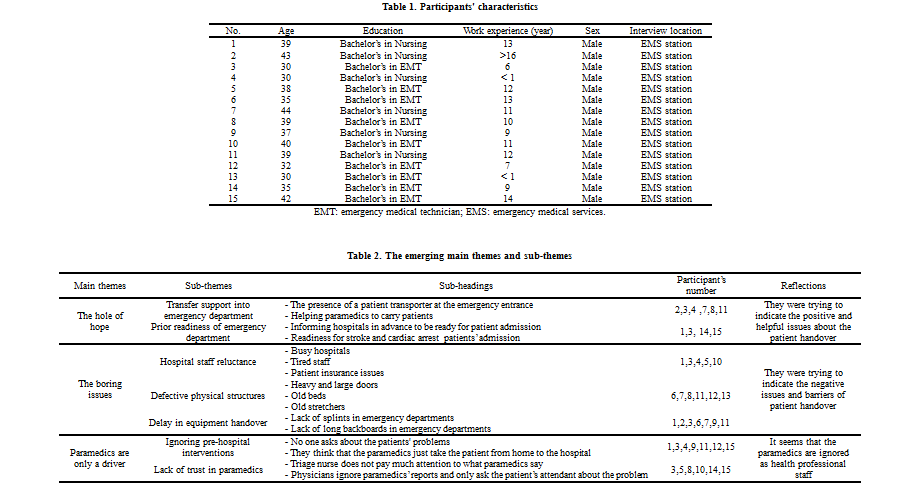

This study was conducted on 15 paramedics in Tabriz City, Iran. All participants were male and had a bachelor’s degree. Demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1. As part of the analysis, each of the interviews was read several times by the authors to extract sub-themes and main themes. Finally, by immersing in the data and reflecting on the themes of this phenomenon, 3 main themes emerged: “the hole of hope,” “the boring issues,” and “paramedics are only a driver.” Further, 11 sub-themes emerged under the main themes (Table 2).

The hole of hope

Due to the participants’ statements, there were some positive and hopeful issues about patient handover that helped paramedics more and ease this process. This main theme includes 2 sub-themes of “transfer support into ED” and “prior readiness of the ED.”

1.1 Transfer support into ED

The sub-theme of “transfer support into ED” was expressed by participants, and they mentioned the importance of staff being available in front of the ED’s door as a key factor in facilitating the patient's transfer from the ambulance trolley onto an emergency bay bed in the ED. One participant noted the need for staff to be at the entrance to conduct a patient handover, "A good thing done by Hospital X is the presence of a patient transporter at the hospital emergency entrance, which facilitates handover" (P8). While another participant stated:

In the last few months, the handover process has been very convenient because there is a patient transporter at the emergency door to allow us to transfer the patient. Previously, we had to find a bed or stretcher ourselves in the emergency room and take the patient to the emergency room without any help, but now it is easier because somebody comes and welcomes us, and we hand over the patient to triage (P2).

1.2 Prior readiness of ED

The sub-theme of “prior readiness of ED” emerged strongly from the interview transcript, mentioning the readiness of ED physicians and nurses as the facilitating factor for accelerating the patient handover process. One participant stated:

I have only seen the prior readiness of the health care team to treat ischemic stroke at X Hospital. The handover of these patients is fast. In triage, a resident receives the patient and takes him/her to the imaging department quickly (P3).

Another participant provided an example of handover when implementing a rapid anticoagulant trial: "… in stroke and CPR patients, we inform hospitals in advance to be ready for patient handover, which eliminates many additional steps, such as waiting to file and staying in line for patient handover" (P1). This pre-hospital information assists with emergency personnel preparedness for receiving the emergency patient.

The boring issues

In addition to some hopeful cases, there were other issues that prevented a quick and easy patient handover process. These issues cause boredom and frustration in paramedics and include 3 sub-themes: “hospital staff reluctance," "defective physical structures," and "delay in equipment handover."

2.1 Hospital staff reluctance

In the sub-theme of “hospital staff reluctance,” participants reported the reluctance of some hospitals to accept patients. According to the paramedics’ experience, for various reasons, including overcrowding and overwork, some ED staff referred them to other medical centers. Emergency departments may suggest transferring patients to another facility when they are busy, citing clinical expertise as a valid reason to do so. For example, a patient who has been transported by the police with both alcohol poisoning and trauma resulting from a fight may require a transfer to a different facility. In this case, the ED may suggest transferring the patient to another hospital that is better equipped to handle the complexities of this presentation. A participant explained,

Y Hospital was also resisting the handover of the patient on the pretext that the patient was a poisoned one and should be hospitalized in X Hospital ... . My impression was that because the emergency department of the X Hospital was overcrowded that day, they wanted to reject the patient with the trauma pretext (P5).

In a similar instance, emergency personnel could be known to become aggressive toward the paramedics when presenting with patients when the department is deemed too busy to accept patients. One physician was noted as saying, “Why did you bring an accident trauma patient here? Don’t you know how busy this place is?” However, the paramedic responded, "Why do you say so? Here is a general hospital; it has everything, including an operating room. If you don’t want to admit this patient, write it down and sign it." When asked by the paramedic to document the non-acceptance of the patient, the physician refused (due to legal issues), stating, “I won't do that, and you should take him away from here” (P10).

2.2 Defective physical structures

Three participants referred to the physical structures of the ED, which included the entrance to the ward, the door, and the transport equipment, as obstacles to the effective handover of patients and can result in delays while paramedics wait to hand over. One participant stated, "We have problems at the X Hospital. Emergency doors are very large and heavy, and it is very difficult to open and close them” (P6). Another stated, “The entrance of the ED of the X Hospital has been poorly designed, and it makes ambulances wait for 15-20 minutes" (P7). Further, the age and location of the emergency trolley were cited as being unsafe for agitated patients, as 1 participant stated, “There are 2 old beds with no safe bed rails in the triage that are really unsafe, so that alcohol- and drug-related patients, most of whom are agitated, are subject to falling out of bed” (P6).

2.3 Delay in equipment handover

Participants mentioned a long wait to take back medical devices used to transport the patients or the injured (especially the neck collar) to the hospital. One participant stated:

When we hand over a trauma patient (back trauma) to the emergency room with a long backboard, we have to wait hours to take it back. After passing the admission stage, we ourselves go to the Emergency Drugstore to take back the collar, but they can easily put several collars in the triage and give it back immediately after the patient handover and record it in the patient's file (P9).

Another participant also mentioned frustrations over the timely replacement of paramedic equipment, "Obstacles to handover are mostly related to the giving back of the equipment, especially neck collar and some splints” (P3).

Paramedics are only a driver

The main theme of “paramedics are only a driver” included 2 sub-themes of “ignoring pre-hospital interventions” and “lack of trust in paramedics.” Participants complained that physicians and nurses in the ED do not pay attention to pre-hospital measures and treat the paramedics only as the carriers and drivers of the patients.

3.1 Ignoring pre-hospital interventions

Participants reported being ignored during pre-hospital transfer by the physicians and nurses working in the ED. One participant noted:

There is no one to ask us about the patients' problems. Physicians and residents do not want patients’ histories. For example, in dealing with a trauma patient, we are not asked how the trauma occurred to the patient, what the scene was like, what parts have tenderness, and what has been done for the patient (P1).

The lack of consideration given to paramedics who present with patients to EDs can potentially lead to adverse outcomes for the patients. As an example, one of the participants explained that because the ED staff did not listen to the paramedic, the patient was inadvertently administered a second dose of medication:

We had a case where the patient had a seizure, and we injected diazepam during transportation, but the physician asked the patient’s attendant about the problem instead of asking us, and then when he was informed that the patient suffered from a seizure, he again prescribed diazepam, which caused a respiratory arrest (P4).

Further, another participant stated:

They treat us superficially and think that the paramedics just take the patient from home to the hospital and we are only a driver. They don't ask us about the history of interventions taken for the patient and don't care about it (P3).

The lack of respect toward the paramedic staff resulted in feelings of disrespect and frustration among paramedics.

3.2 Lack of trust in paramedics

The lack of trust in paramedics was experienced by some of the participants while handing over a patient to the ED. One participant shared an experience where they presented a patient with chest pain to the hospital staff, but the staff seemed reluctant to listen to the paramedic:

When I handed him over to the hospital triage, I told them that he was a critically ill patient and he should be taken immediately to the CPR room, but the people working in the triage did not pay much attention to what I said, and I found they don't trust me (P10).

Fortunately, in this particular case, the paramedic did not leave and stayed by the patient's side. Together with a nurse, they performed an electrocardiogram (ECG) and identified a dangerous heart rhythm. As a result, the patient was transferred to a monitored bed for specialized cardiac care. In a similar incident, a paramedic officer handed over a patient with an allergy to diazepam; however, the ED staff did not take note of this vital information:

When I handed over the patient to the resuscitation room, I told the resident that this patient was allergic to diazepam because I knew they might inject diazepam into the patient because of his condition. Although I said the patient was allergic to diazepam, they did not pay attention to my words, and the patient immediately developed a fatal respiratory arrest. They resuscitated the patient, but he passed away (P15).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the experiences of paramedics from patient handover to the ED personnel in the northwest of Iran.

The hole of hope

In this study, as the hole of hope, the staff being available in front of the ED’s door to facilitate the patient's transfer from the ambulance trolley onto an emergency bay bed, and the prior readiness of ED personnel was the factor that helped paramedics more and eased patient handover. Bost et al, with the aim of exploring the process of transferring a patient from an ambulance to an ED in Australia, showed that to facilitate and expedite the care for a critically ill patient, the emergency ward of the hospital was informed that a critically ill patient was on the way to reach hospital through telephone or radio call and the medical team was prepared to hand over the patient (6). Also, in the studies by Prestes et al and Najafi et al, the positive effects of welcoming patients in front of the emergency door by the ED staff were pointed out (12, 13).

The boring issues

In the current study, the paramedics also experienced some factors that hindered their ability to conduct ambulance-to-ED handover processes and caused boredom and frustration in paramedics. The reluctance of some hospitals to admit patients, defective equipment, the physical structures of some hospitals, and delay in equipment handover were mentioned as examples of handover inhibitors. Consistent with the findings of the current study, Khorgami et al showed that ED personnel refused to admit patients for various reasons, including overcrowding and overwork, and referred them to other medical centers (14). Contrary to the findings of the current study, Bost et al found that none of the patients was rejected because of the busy ED, and they were not transferred to another hospital. The main cause of paramedics’ waiting in hospitals was overcrowded ED and lack of bed vacancy; however, there was no talk of a delay in giving back the equipment (6). Consistent with the results of the current study, Fazel et al and Mohammadi et al also mentioned defective equipment and emergency beds as the inhibitors to the handover process (15, 16).

Paramedics are only a driver

In this study, hospital physicians and nurses do not appear to trust the clinical competence (patient assessment and history taking) of paramedics; therefore, they do not care about interventions given to patients, viewing the paramedics as mere drivers whose sole responsibility is to take patients from the place of accident to the hospital. According to the Paramedic Association of Canada and Paramedics Australasia, the paramedics’ core competencies include professional responsibilities, communication, differential diagnosis skills, decision-making skills, psychomotor skills, transportation, health promotion and public safety, evidence-based practice, assessment and history taking, and team working (17, 18). In the study conducted by Salehi et al, over 85% of emergency nurses have low knowledge of the competencies of paramedics, which has a negative impact on the quality of the patient handover process (3). Bayrami et al investigated the challenges faced by pre-hospital paramedics in Mashhad City. The findings revealed that many people viewed paramedics as drivers who transport patients from their homes to hospitals. Consequently, in situations where only transportation to the hospital is required, unnecessary calls to EMS are common in Iran (19).

The findings of the current study provided examples of miscommunication between the paramedics and ED personnel, which, in some cases, resulted in the patient's condition worsening. In the study by de Lange et al, the participants did not care much about the patient during handover, as they did not have prior information and readiness to admit patients to the ED, and their priority and concern were who and how to transfer the patient from ambulance to the ED (20). In the study of De Lange et al, nurses and physicians in the ED did not listen to the paramedics’ explanations or care much about them (20). In other studies, the results showed that paramedics expressed great concern about the lack of respect received by ED nurses during the patient handover, and they noted the lack of consideration during patient handovers as an important challenge that continues even today (1, 6, 21).

Conclusion

The process of transferring patients from paramedics to ED personnel required restructuring and a shift in the physicians’ and nurses' perceptions of paramedics' abilities, as well as changes in all aspects of the hospital's management. In other words, the meaning of patient handover from paramedics’ perspective is hard work that they have to do in hospitals with defective physical structures, tired staff, lack of equipment, and lack of trust in their knowledge and abilities, though with the hope of the presence of somebody at the emergency entrance to help them carrying the patient into the emergency ward. In addition, conducting further studies to investigate why some hospitals refuse to admit patients could enhance the ambulance-to-ED handover process.

Limitations of the study

There were limitations encountered throughout the study. The current study reported the experiences of male paramedics that were limited to an Iranian context. Moreover, the study would be much stronger if the method was used to concurrently gather the experiences and perspectives of the ED staff to further elucidate the differing perspectives and opportunities for improvement. Further research is recommended to compare these results internationally.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the participants who gave freely of their time to participate in the study. However, the ethical approval was obtained by the Regional Committee of the Medical Research Ethics at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences with code number 5/4/21.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the deputy of research in Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethic committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1395.296).

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Hamidreza Haririan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Analysis, and Writing - Original Draft. Hadi Hassankhani: Conceptualization, Analysis, and funding acquisition. Joanne Porter and Abraham Oshni Alvandi: Writing - Review & Critical revisions for important intellectual content.

Patient handover in the emergency department (ED) is a 2-way communication process between the paramedics and in-hospital emergency personnel, which can result in miscommunication and delivery challenges (1). Pre-hospital emergency services play a crucial role in the health care system by transferring vital information about the patient to ED personnel, particularly in situations involving time-critical and urgent care. To improve the quality of patient care in the ED, focus should be placed on all stages of the communication delivery process, including how to transfer and hand over patients from the pre-hospital emergency setting to the in-hospital emergency personnel (2).

Patient handover refers to the process of transferring patient care information and responsibility from 1 care provider or team to another, which plays an important role in each patients’ clinical safety and harm minimization (3). In European countries, 25%-40% of unwanted adverse events occur during patient handover (4). According to the US Patient Safety Committee, an inappropriate patient handover, in which patient information is not fully transferred, accounts for 65% of the irreversible damage to patients. Some of the adverse events related to poor handover included delays in treatment or procedure, prolonged treatment or procedure (leading to patient deterioration), errors involving medications, lack of monitoring information given on clinical assessment, patient falls, and disruptive and aggressive behavior toward patients (5). A study investigated the clinical handover processes between Australian ambulance personnel and ED staff for patients arriving by ambulance, showing that the quality of handover is influenced by various factors, including the expectations of personnel, their prior experience, workload, and working relationships. However, issues such as a lack of active listening and limited access to written information were identified as contributing factors. This study also demonstrated the complexity of clinical handover from the ambulance service to the ED (6).

A voluntary reporting of adverse events in Iranian hospitals demonstrated that almost 7% of these events are caused by an inappropriate patient handover, highlighting the critical role of staff in completing accurate documentation and online reporting to prevent such incidents (7). Salehi et al (2016) conducted a study with the aim of identifying areas for improvement in patient handover, specifically focusing on the communication process between paramedics and ED nurses. The results of the study revealed that most miscommunication occurred due to a lack of knowledge regarding the relevant protocols, as well as communication challenges between triage nurses and paramedics during patient handover. These issues could potentially result in an increased number of adverse events for patients (3).

In road collisions in Iran, over 88.46% of injured patients are transported by ambulance to hospitals requiring a clinical handover (8). Jamshidi et al (2019) conducted a qualitative study with the aim of determining the challenges of cooperation between the pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency services in the handover of victims of road traffic accidents in Iran. Through purposive sampling, 15 employees from ambulance personnel and hospital emergency staff were interviewed, and they expressed their experiences of cooperation between these 2 teams in the handover of traffic accident casualties. The data analysis revealed 3 major challenges associated with ambulance patient handover: a shortage of infrastructure resources, inefficient and unscientific management, and non-common language (9). Moreover, little information is available on the experience of Iranian paramedics in patient handover to hospitals.

Given the importance of patient safety with a focus on the prevention of adverse events during handover and with the help of qualitative research to better identify unknown aspects of the phenomenon, this study aimed to explore the lived experience of paramedics during patient handover to ED personnel.

Methods

In this qualitative study, an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was used to identify the meaning of patient handover from the paramedics’ perspective in this study. The primary focus of IPA is the lived experience of participants and the meaning they make of this experience, but the end result is an interpretation of how the researcher thinks the participant is thinking. This analysis is an iterative process and involves moving between the part and the whole of the hermeneutic circle (10).

Participants were recruited using a purposeful sampling technique via Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in Tabriz City, Iran. As part of the inclusion criteria, participants who had the patient handover experience and expressed a willingness to participate in the study were invited, and there were no exclusion criteria based on age or ethnicity. Fifteen paramedics participated in this study over a period of 5 months (from November 2017 to April 2018). The sample size was determined according to the time when data richness was achieved. Data collection ended when the data was considered rich and varied enough to illuminate the phenomenon and when no new themes emerged. Variation within the data was enhanced by purposeful sampling and recruiting paramedics with work experience from less than 1 year to more than 16 years.

Participants were contacted via phone, face-to-face meetings, and emails. Semi-structured interviews (50-60 minutes) were conducted in the EMS stations or at a location and time preferred by the participants. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by the corresponding author. Demographic data were asked, followed by a series of interview guides exploring the participants’ experiences during the patient handover. Interview questions (interview guide) included “tell me your experiences regarding patient handover” and “what happened when you did patient handover.” Overall, 16 interview sessions were held with 16 participants. However, data richness was obtained after 15 interviews with no new emerging themes identified. Repeat interviews were not carried out.

Written consent was obtained from each participant prior to the interview, and fictitious and numerical names were assigned to maintain confidentiality. However, interviews conducted at the station may threaten anonymity; in this regard, the name and place of EMS stations did not mention in the text. The Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1395.296) approved this study.

A 6-step analysis process of the Smith, Flowers, and Larkin approach used as follows: 1) reading and re-reading, 2) initial noting, 3) developing emergent themes, 4) searching for connections across emergent themes, 5) moving to the next case, and 6) looking for patterns across cases. The themes included if stated by at least 3 or more participants (10). MAXQDA software (release 18.2.5) was used to manage data analysis.

The researcher used 4 criteria to ensure rigor and accuracy, including credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability, according to Lincoln and Guba (11). The interview transcripts were returned to the participants to ensure the accuracy of the codes and interpretations, increasing the credibility of the data. Participant checking did not result in any amendments, and participants felt they were accurate. An audit trail was used to control the dependability of the data, and an independent scrutiny of qualitative data and relevant documents by an external reviewer was obtained to evaluate the dependability of the data. However, the peer check approach was used to control data conformability. In addition, the authors’ detailed description ensured the transferability of the data (11).

Results

This study was conducted on 15 paramedics in Tabriz City, Iran. All participants were male and had a bachelor’s degree. Demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1. As part of the analysis, each of the interviews was read several times by the authors to extract sub-themes and main themes. Finally, by immersing in the data and reflecting on the themes of this phenomenon, 3 main themes emerged: “the hole of hope,” “the boring issues,” and “paramedics are only a driver.” Further, 11 sub-themes emerged under the main themes (Table 2).

The hole of hope

Due to the participants’ statements, there were some positive and hopeful issues about patient handover that helped paramedics more and ease this process. This main theme includes 2 sub-themes of “transfer support into ED” and “prior readiness of the ED.”

1.1 Transfer support into ED

The sub-theme of “transfer support into ED” was expressed by participants, and they mentioned the importance of staff being available in front of the ED’s door as a key factor in facilitating the patient's transfer from the ambulance trolley onto an emergency bay bed in the ED. One participant noted the need for staff to be at the entrance to conduct a patient handover, "A good thing done by Hospital X is the presence of a patient transporter at the hospital emergency entrance, which facilitates handover" (P8). While another participant stated:

In the last few months, the handover process has been very convenient because there is a patient transporter at the emergency door to allow us to transfer the patient. Previously, we had to find a bed or stretcher ourselves in the emergency room and take the patient to the emergency room without any help, but now it is easier because somebody comes and welcomes us, and we hand over the patient to triage (P2).

1.2 Prior readiness of ED

The sub-theme of “prior readiness of ED” emerged strongly from the interview transcript, mentioning the readiness of ED physicians and nurses as the facilitating factor for accelerating the patient handover process. One participant stated:

I have only seen the prior readiness of the health care team to treat ischemic stroke at X Hospital. The handover of these patients is fast. In triage, a resident receives the patient and takes him/her to the imaging department quickly (P3).

Another participant provided an example of handover when implementing a rapid anticoagulant trial: "… in stroke and CPR patients, we inform hospitals in advance to be ready for patient handover, which eliminates many additional steps, such as waiting to file and staying in line for patient handover" (P1). This pre-hospital information assists with emergency personnel preparedness for receiving the emergency patient.

The boring issues

In addition to some hopeful cases, there were other issues that prevented a quick and easy patient handover process. These issues cause boredom and frustration in paramedics and include 3 sub-themes: “hospital staff reluctance," "defective physical structures," and "delay in equipment handover."

2.1 Hospital staff reluctance

In the sub-theme of “hospital staff reluctance,” participants reported the reluctance of some hospitals to accept patients. According to the paramedics’ experience, for various reasons, including overcrowding and overwork, some ED staff referred them to other medical centers. Emergency departments may suggest transferring patients to another facility when they are busy, citing clinical expertise as a valid reason to do so. For example, a patient who has been transported by the police with both alcohol poisoning and trauma resulting from a fight may require a transfer to a different facility. In this case, the ED may suggest transferring the patient to another hospital that is better equipped to handle the complexities of this presentation. A participant explained,

Y Hospital was also resisting the handover of the patient on the pretext that the patient was a poisoned one and should be hospitalized in X Hospital ... . My impression was that because the emergency department of the X Hospital was overcrowded that day, they wanted to reject the patient with the trauma pretext (P5).

In a similar instance, emergency personnel could be known to become aggressive toward the paramedics when presenting with patients when the department is deemed too busy to accept patients. One physician was noted as saying, “Why did you bring an accident trauma patient here? Don’t you know how busy this place is?” However, the paramedic responded, "Why do you say so? Here is a general hospital; it has everything, including an operating room. If you don’t want to admit this patient, write it down and sign it." When asked by the paramedic to document the non-acceptance of the patient, the physician refused (due to legal issues), stating, “I won't do that, and you should take him away from here” (P10).

2.2 Defective physical structures

Three participants referred to the physical structures of the ED, which included the entrance to the ward, the door, and the transport equipment, as obstacles to the effective handover of patients and can result in delays while paramedics wait to hand over. One participant stated, "We have problems at the X Hospital. Emergency doors are very large and heavy, and it is very difficult to open and close them” (P6). Another stated, “The entrance of the ED of the X Hospital has been poorly designed, and it makes ambulances wait for 15-20 minutes" (P7). Further, the age and location of the emergency trolley were cited as being unsafe for agitated patients, as 1 participant stated, “There are 2 old beds with no safe bed rails in the triage that are really unsafe, so that alcohol- and drug-related patients, most of whom are agitated, are subject to falling out of bed” (P6).

2.3 Delay in equipment handover

Participants mentioned a long wait to take back medical devices used to transport the patients or the injured (especially the neck collar) to the hospital. One participant stated:

When we hand over a trauma patient (back trauma) to the emergency room with a long backboard, we have to wait hours to take it back. After passing the admission stage, we ourselves go to the Emergency Drugstore to take back the collar, but they can easily put several collars in the triage and give it back immediately after the patient handover and record it in the patient's file (P9).

Another participant also mentioned frustrations over the timely replacement of paramedic equipment, "Obstacles to handover are mostly related to the giving back of the equipment, especially neck collar and some splints” (P3).

Paramedics are only a driver

The main theme of “paramedics are only a driver” included 2 sub-themes of “ignoring pre-hospital interventions” and “lack of trust in paramedics.” Participants complained that physicians and nurses in the ED do not pay attention to pre-hospital measures and treat the paramedics only as the carriers and drivers of the patients.

3.1 Ignoring pre-hospital interventions

Participants reported being ignored during pre-hospital transfer by the physicians and nurses working in the ED. One participant noted:

There is no one to ask us about the patients' problems. Physicians and residents do not want patients’ histories. For example, in dealing with a trauma patient, we are not asked how the trauma occurred to the patient, what the scene was like, what parts have tenderness, and what has been done for the patient (P1).

The lack of consideration given to paramedics who present with patients to EDs can potentially lead to adverse outcomes for the patients. As an example, one of the participants explained that because the ED staff did not listen to the paramedic, the patient was inadvertently administered a second dose of medication:

We had a case where the patient had a seizure, and we injected diazepam during transportation, but the physician asked the patient’s attendant about the problem instead of asking us, and then when he was informed that the patient suffered from a seizure, he again prescribed diazepam, which caused a respiratory arrest (P4).

Further, another participant stated:

They treat us superficially and think that the paramedics just take the patient from home to the hospital and we are only a driver. They don't ask us about the history of interventions taken for the patient and don't care about it (P3).

The lack of respect toward the paramedic staff resulted in feelings of disrespect and frustration among paramedics.

3.2 Lack of trust in paramedics

The lack of trust in paramedics was experienced by some of the participants while handing over a patient to the ED. One participant shared an experience where they presented a patient with chest pain to the hospital staff, but the staff seemed reluctant to listen to the paramedic:

When I handed him over to the hospital triage, I told them that he was a critically ill patient and he should be taken immediately to the CPR room, but the people working in the triage did not pay much attention to what I said, and I found they don't trust me (P10).

Fortunately, in this particular case, the paramedic did not leave and stayed by the patient's side. Together with a nurse, they performed an electrocardiogram (ECG) and identified a dangerous heart rhythm. As a result, the patient was transferred to a monitored bed for specialized cardiac care. In a similar incident, a paramedic officer handed over a patient with an allergy to diazepam; however, the ED staff did not take note of this vital information:

When I handed over the patient to the resuscitation room, I told the resident that this patient was allergic to diazepam because I knew they might inject diazepam into the patient because of his condition. Although I said the patient was allergic to diazepam, they did not pay attention to my words, and the patient immediately developed a fatal respiratory arrest. They resuscitated the patient, but he passed away (P15).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the experiences of paramedics from patient handover to the ED personnel in the northwest of Iran.

The hole of hope

In this study, as the hole of hope, the staff being available in front of the ED’s door to facilitate the patient's transfer from the ambulance trolley onto an emergency bay bed, and the prior readiness of ED personnel was the factor that helped paramedics more and eased patient handover. Bost et al, with the aim of exploring the process of transferring a patient from an ambulance to an ED in Australia, showed that to facilitate and expedite the care for a critically ill patient, the emergency ward of the hospital was informed that a critically ill patient was on the way to reach hospital through telephone or radio call and the medical team was prepared to hand over the patient (6). Also, in the studies by Prestes et al and Najafi et al, the positive effects of welcoming patients in front of the emergency door by the ED staff were pointed out (12, 13).

The boring issues

In the current study, the paramedics also experienced some factors that hindered their ability to conduct ambulance-to-ED handover processes and caused boredom and frustration in paramedics. The reluctance of some hospitals to admit patients, defective equipment, the physical structures of some hospitals, and delay in equipment handover were mentioned as examples of handover inhibitors. Consistent with the findings of the current study, Khorgami et al showed that ED personnel refused to admit patients for various reasons, including overcrowding and overwork, and referred them to other medical centers (14). Contrary to the findings of the current study, Bost et al found that none of the patients was rejected because of the busy ED, and they were not transferred to another hospital. The main cause of paramedics’ waiting in hospitals was overcrowded ED and lack of bed vacancy; however, there was no talk of a delay in giving back the equipment (6). Consistent with the results of the current study, Fazel et al and Mohammadi et al also mentioned defective equipment and emergency beds as the inhibitors to the handover process (15, 16).

Paramedics are only a driver

In this study, hospital physicians and nurses do not appear to trust the clinical competence (patient assessment and history taking) of paramedics; therefore, they do not care about interventions given to patients, viewing the paramedics as mere drivers whose sole responsibility is to take patients from the place of accident to the hospital. According to the Paramedic Association of Canada and Paramedics Australasia, the paramedics’ core competencies include professional responsibilities, communication, differential diagnosis skills, decision-making skills, psychomotor skills, transportation, health promotion and public safety, evidence-based practice, assessment and history taking, and team working (17, 18). In the study conducted by Salehi et al, over 85% of emergency nurses have low knowledge of the competencies of paramedics, which has a negative impact on the quality of the patient handover process (3). Bayrami et al investigated the challenges faced by pre-hospital paramedics in Mashhad City. The findings revealed that many people viewed paramedics as drivers who transport patients from their homes to hospitals. Consequently, in situations where only transportation to the hospital is required, unnecessary calls to EMS are common in Iran (19).

The findings of the current study provided examples of miscommunication between the paramedics and ED personnel, which, in some cases, resulted in the patient's condition worsening. In the study by de Lange et al, the participants did not care much about the patient during handover, as they did not have prior information and readiness to admit patients to the ED, and their priority and concern were who and how to transfer the patient from ambulance to the ED (20). In the study of De Lange et al, nurses and physicians in the ED did not listen to the paramedics’ explanations or care much about them (20). In other studies, the results showed that paramedics expressed great concern about the lack of respect received by ED nurses during the patient handover, and they noted the lack of consideration during patient handovers as an important challenge that continues even today (1, 6, 21).

Conclusion

The process of transferring patients from paramedics to ED personnel required restructuring and a shift in the physicians’ and nurses' perceptions of paramedics' abilities, as well as changes in all aspects of the hospital's management. In other words, the meaning of patient handover from paramedics’ perspective is hard work that they have to do in hospitals with defective physical structures, tired staff, lack of equipment, and lack of trust in their knowledge and abilities, though with the hope of the presence of somebody at the emergency entrance to help them carrying the patient into the emergency ward. In addition, conducting further studies to investigate why some hospitals refuse to admit patients could enhance the ambulance-to-ED handover process.

Limitations of the study

There were limitations encountered throughout the study. The current study reported the experiences of male paramedics that were limited to an Iranian context. Moreover, the study would be much stronger if the method was used to concurrently gather the experiences and perspectives of the ED staff to further elucidate the differing perspectives and opportunities for improvement. Further research is recommended to compare these results internationally.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the participants who gave freely of their time to participate in the study. However, the ethical approval was obtained by the Regional Committee of the Medical Research Ethics at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences with code number 5/4/21.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the deputy of research in Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethic committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1395.296).

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Hamidreza Haririan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Analysis, and Writing - Original Draft. Hadi Hassankhani: Conceptualization, Analysis, and funding acquisition. Joanne Porter and Abraham Oshni Alvandi: Writing - Review & Critical revisions for important intellectual content.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. Sanjuan-Quiles Á, del Pilar Hernández-Ramón M, Juliá-Sanchis R, García-Aracil N, Castejón-de la Encina ME, Perpiñá-Galvañ J. Handover of patients from prehospital emergency services to emergency departments: a qualitative analysis based on experiences of nurses. J Nurs Care Qual. 2019;34(2):169-74. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Marmor GO, Li MY. Improving emergency department medical clinical handover: Barriers at the bedside. Emerg Med Australas. 2017;29(3):297-302. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Salehi S, Zarea K, Mohammadi AA. Patient Handover Process Problems between Emergency Medical Service Personnel and Emergency Department Nurses. Iran J Emerg Med. 2016;4(1):27-34. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

4. Bergs J, Lambrechts F, Mulleneers I, Lenaerts K, Hauquier C, Proesmans G, et al. A tailored intervention to improving the quality of intrahospital nursing handover. Int Emerg Nurs. 2018;36:7-15. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

5. Fahim Yegane SA, Shahrami A, Hatamabadi HR, Hosseini-Zijoud S-M. Clinical Information Transfer between EMS Staff and Emergency Medicine Assistants during Handover of Trauma Patients. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32(5):541-7. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

6. Bost N, Crilly J, Patterson E, Chaboyer W. Clinical handover of patients arriving by ambulance to a hospital emergency department: A qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20(3):133-41. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

7. Kakemam E, Hajizadeh A, Azarmi M, Zahedi H, Gholizadeh M, Roh YS. Nurses' perception of teamwork and its relationship with the occurrence and reporting of adverse events: A questionnaire survey in teaching hospitals. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(5):1189-98. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

8. Barzegar A, Ghadipasha M, Forouzesh M, Valiyari S, Khademi A. Epidemiologic study of traffic crash mortality among motorcycle users in Iran. Chin J Traumatol. 2020;23(4):219-23. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

9. Jamshidi H, Jazani RK, Alibabaei A, Alamdari S, Kalyani MN. Challenges of Cooperation between the Pre-hospital and In-hospital Emergency services in the handover of victims of road traffic accidents: A Qualitative Study. Invest Educ Enferm. 2019;37(1):70-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

10. Smith JA, Fieldsend M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2021. p:147-66. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

11. Polit D, Beck C. Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

12. Prestes JM, Klein AS, Kruel AJ, Martins AM, Ribeiro CR, Anschau F. Welcoming protocol in the maximum restriction of the emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Brazil. Archives of Nursing Practice and Care. 2020;6(1):035-41. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

13. Najafi Ghezeljeh T, Keyvanloo Shahrestanaki S, Mohammadbeigi T, Haghani S. Patient Safety Competency in Emergency Nurses in Educational-Medical Centers of Iran University of Medical Sciences. Iran J Nurs. 2022;34(134):60-73. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

14. Khorgami Z, Gougol AH, Soroush A. Causes of deceptive non-admission to the emergency department: personnel's point of view. IJMEHM. 2012;5(3):81-90. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

15. Fazel N, Yazdi Moghadam H, Elhani F, Pejhan A, Koshan M, Ghasemi MR, et al. The Nursing Experiences Regarding to Clinical Education in Emergency Department: A Qualitative Content Analysis in 2012. Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. 2017;24(2):97-106. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

16. Mohammadi, M., Firouzkouhi, M., Abdollahimohammad, A., Shivanpour, M. The Challenges of Pre-Hospital Emergency Personnel in Sistan Area: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences, 2019;8(3):221-32. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

17. Batt A, Poirier P, Bank J, Bolster J, Bowles R, Cameron C, et al. Developing the National Occupational Standard for Paramedics in Canadaupdate 2. Canadian Paramedicine. 2022;45:6-8. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

18. Williams B, Beovich B, Olaussen A. The definition of paramedicine: an international delphi study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:3561-70. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

19. Bayrami R, Ebrahimipour H, Rezazadeh A. Challenges in Pre hospital emergency medical service in Mashhad: A qualitative study. JHOSP. 2017;16(2):82-90. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

20. De Lange S, van Eeden I, Heyns T. Patient handover in the emergency department: 'How' is as important as 'what'. Int Emerg Nurs. 2018;36:46-50. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

21. Dúason S, Gunnarsson B, Svavarsdóttir MH. Patient handover between ambulance crew and healthcare professionals in Icelandic emergency departments: a qualitative study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29:21. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |