Volume 20, Issue 1 (4-2023)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2023, 20(1): 56-60 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mehrab-Mohseni T, Pashaeypoor S, Nazari S, Sharifi F. The effects of self-care education based on the family-centered empowerment model on functional independence and life satisfaction among community-dwelling older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2023; 20 (1) :56-60

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1430-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1430-en.html

1- Department of Community Health and Geriatric Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Community Based Participatory Research Center, Iranian Institute for Reduction of High – Risk Behaviors, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,sh-pashaeipour@tums.ac.ir

3- Elderly Health Research Center, Endocrinology and Metabolism Population Sciences Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Community Based Participatory Research Center, Iranian Institute for Reduction of High – Risk Behaviors, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,

3- Elderly Health Research Center, Endocrinology and Metabolism Population Sciences Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Keywords: Self-care, Family-Centered Empowerment Model, Functional Status, Life satisfaction, Frail elderly

Full-Text [PDF 490 kb]

(1607 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4122 Views)

Full-Text: (722 Views)

Introduction

Aging is associated with different changes in different body systems. Musculoskeletal changes (such as muscular atrophy) alter walking and reduce mobility. Neurological, dermatological, urinary, and cardiopulmonary changes (such as reduced cardiac capacity, myocardial contractility, and cardiac output) are also very common among older adults.

Age-related changes reduce cognitive, mental, and functional abilities, increase older adults’ dependence on others, weaken social support, and lead to loneliness and acute and chronic health problems (1, 2). Reduced functional abilities and increased dependence on others are, in turn, associated with the development of different disabilities, hospitalization, increased health care costs and caregiver burden, and death (3, 4). Evidence shows that 1.3% of older adults over 65 years live alone. Loneliness can aggravate problems in doing daily activities and increase the risk of social isolation (4). A study reported that dependence on doing daily activities increases the sense of loneliness and insecurity and causes fears over communicating with family members (3). Contrarily, older adults with independence in their activities feel greater self-esteem, self-confidence (5), self-control, self-worth, and life satisfaction (6).

Dependency in older adults can significantly affect their life satisfaction. Life satisfaction is a cognitive component of subjective well-being and refers to individuals’ judgment about life as a whole. High levels of life satisfaction promote successful coping with different life conditions and age-related limitations and, thereby, give older adults a sense of happiness (7). Life satisfaction is determined by many different factors, such as independence, healthy lifestyle, and lifestyle education. A study reported that independence and participation in social activities provide older adults with more social opportunities, give them a sense of significance and self-efficacy, and improve their life satisfaction (8). Another study found that healthy lifestyle education based on physical exercise, sleep-activity balance, and stress management had significantly positively affected life satisfaction (9).

Self-care is a significant factor affecting independence and life satisfaction (10). Self-care refers to the ability to perform activities to prevent illness, maintain and promote health, and cope with illnesses and disabilities (11). Self-care in older adults is affected by age-related problems, such as physical and mental problems and disabilities (12). A study reported that self-care limitations are five times more prevalent among older adults with chronic illnesses (13). Another study showed poor self-care ability among 98% of older adults (14). Moreover, older adults who live alone have a lower desire for engagement in self-care activities (15). Therefore, older adults need support, particularly family support, to actively engage in self-care activities. A study reported that family support can increase older adults’ desire and motivation for doing self-care activities (16).

Self-care education is a method with potentially positive effects on self-care. A systematic method for self-care education is education based on the family-centered empowerment model (FCEM). FCEM was introduced in 2002 by Alhani to empower the family system for health promotion. The main steps of this model are perceived threat, problem-solving, educational participation, and evaluation (17). This model has so far been used in different studies on patients with myocardial infarction (18), asthma (19), and other chronic diseases (20). Most previous studies on self-care among older adults have focused on those with chronic illnesses (20, 21), and there are limited data about self-care and healthy lifestyles among community-dwelling older adults (22). The present study sought to narrow this gap. The study aimed to determine the effects of FCEM-based self-care education on functional independence and life satisfaction among community-dwelling older adults.

Methods

Design

This randomized clinical trial was conducted on community-dwelling older adults from July to October 2021.

Participants and setting

A total of 126 eligible older adults were recruited from local sociocultural centers using a convenience sampling method in District 6 of Tehran City, Iran. Inclusion criteria were the age of 60-75 years, living with a spouse or children, having no participation in self-care–related educational programs in the past year, having the ability to speak Persian, and having a family member with the ability to participate in educational sessions. Participants were excluded if they developed acute health problems, were hospitalized, or had 2 consecutive absences from the intervention sessions. They were randomly allocated into control (A) and intervention (B) groups via block randomization with a block size of 4. Accordingly, 6 possible blocks were designed and numbered 1-6 as follows: 1) AABB, 2) ABAB, 3) ABBA, 4) BBAA, 5) BABA, and 6) BAAB. Then, a randomization sequence was generated using an online randomizer (ie, www.randomization.com). For allocation concealment, each generated sequence was written on a card, and the card was put in an opaque bag. Bags were randomly selected during sampling, and participants were allocated to groups using the sequences in the bags. Participants did not know whether they were in the intervention or control group. The present study was a double-blind study that blinding was performed for a person who gave a statistical analysis.

The sample size was calculated with a confidence level of 0.95, power of 0.90, and satisfaction mean score of 16.02±4.22 in the intervention group and 12.13±4.15 in the control group (23). Accordingly, the sample size calculation formula showed that 50 persons per group were needed. Nonetheless, the sample size was increased to 63 per group to compensate for probable attrition.

N1 = [(Zα/2 + Zβ)2 × (σ1 + σ2)]/ (μ1 - μ2)2

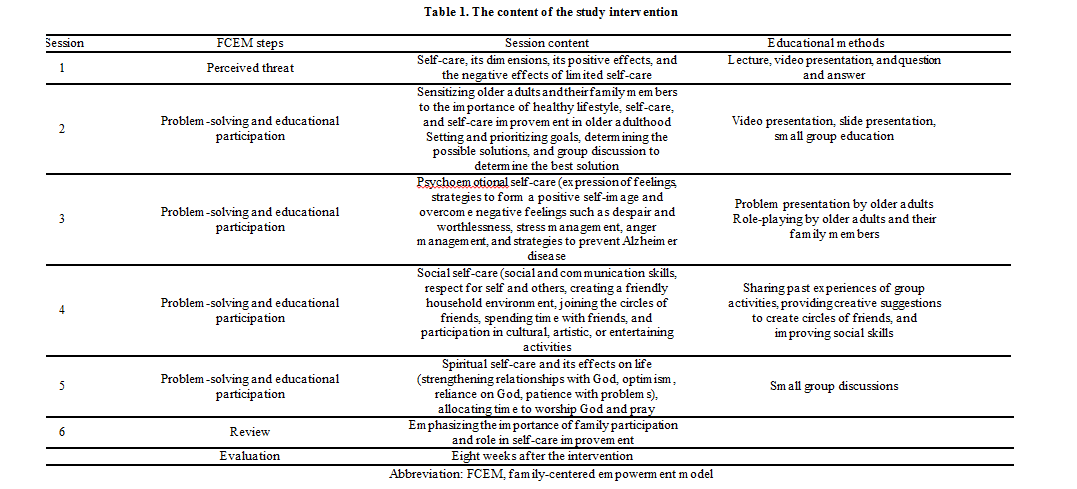

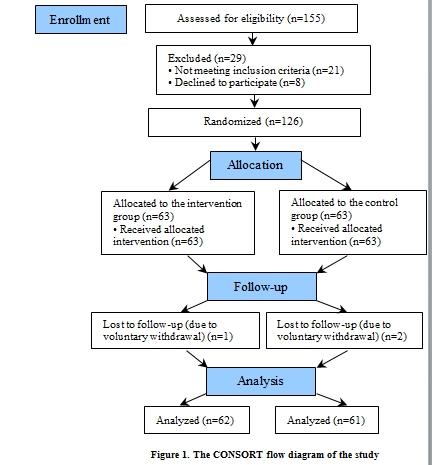

A total of 126 older adults were recruited to the study and allocated to two 63-person groups. One participant from the intervention group and 2 participants from the control group were excluded due to voluntary withdrawal. Data analysis was performed on the data obtained from 62 participants in the intervention group and 61 participants in the control group (Figure 1).

Outcomes and instruments

The primary outcomes were life satisfaction and functional independence. Data collection instruments were a demographic questionnaire, Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (Katz ADL Index), and Zest Life Satisfaction Index. The demographic checklist included age, gender, height, weight, educational level, marital status, number of children, living arrangement, source of income, family financial status, home type, affliction by serious illnesses, and medication use.

The Katz ADL Index was used for functional independence assessment. This index assesses functional independence in 8 areas: bathing, toileting, continence, feeding, dressing, transferring, personal grooming, and walking. Items are scored as follows: 0, dependent; 1, needs help; and 2, “independent.” Therefore, the possible total score of the index is 0-16, which is interpreted as follows: scores 0-7, dependent; scores 8-11, needs help; and scores 12-16, independent (24). A study in Iran reported a content validity index of more than 0.82. Convergent validity showed that the mean scores of ADL and IADL in elderly individuals with normal and adverse normal cognitive abilities were significantly different. Also, the studied instruments were able to differentiate between different age groups. The sensitivity and specificity of ADL and IADL were 0.75 and 0.96, respectively. Cronbach α and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were more than 0.75 (24).

The Zest Life Satisfaction Index was used for life satisfaction assessment. This index has 13 positively and negatively worded items. Positively worded items are scored as follows: 0, I don’t know; 1, disagree; and 2, agree. Negatively worded items are scored as follows: 0, I don’t know; 2, disagree; and 1, agree. The possible total score of the index is 0-26, with higher scores showing higher life satisfaction. A study in Iran confirmed that the index has acceptable validity and reliability through the known-group comparison method and a Cronbach α of 0.79. The item-total correlation and test-retest confirmed its reliability, too (25).Participants completed the study instruments through the self-report method at 2 time points, namely, before and 8 weeks after the study intervention.

Intervention

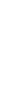

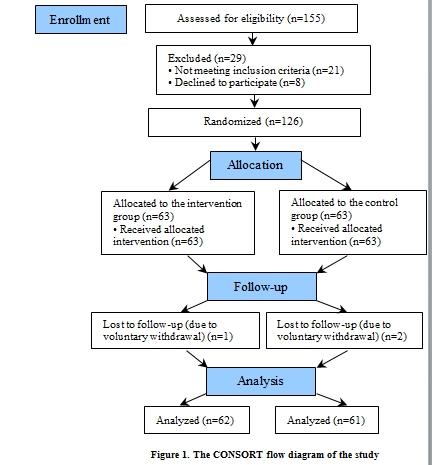

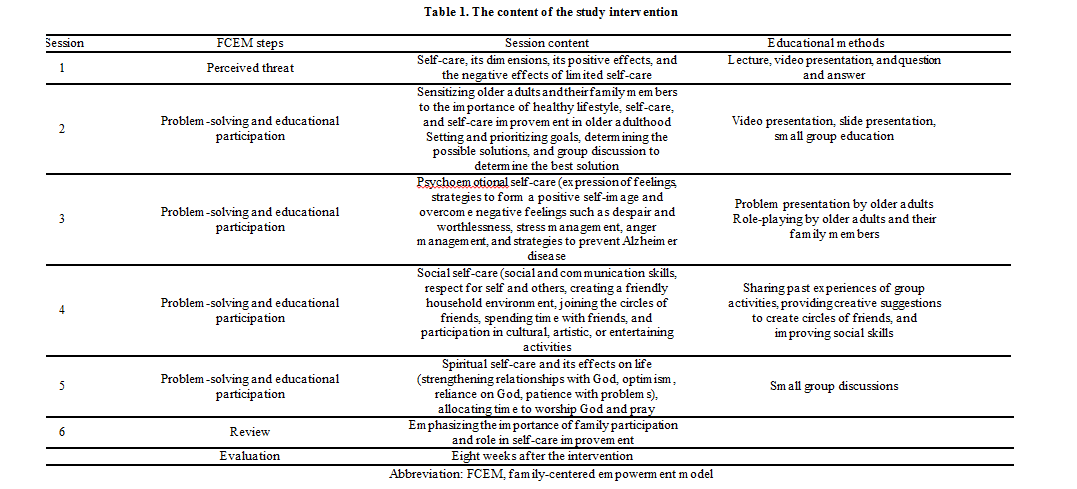

The study intervention was FCEM-based self-care education in physical, mental, social, and spiritual dimensions. The main focus of the study intervention was on active and healthy lifestyles. The intervention was implemented based on the 4 steps of FCEM, namely, perceived threat, problem-solving, educational participation, and evaluation. Education was provided in six 1.5-hour weekly sessions (Table 1) using the lecture, question-and-answer, and group discussions. Participants received education in small groups (9 groups of 7 participants) and had active participation in the educational sessions through role-playing and experience sharing. Since the research setting was a sociocultural center and the elderly came to spend their free time, for this reason, they were not familiar with each other, and the possibility of contamination bias was minimized. Randomization also helped to reduce this bias. The control group received education routinely provided in the study setting in addition to a single self-care education session and an educational pamphlet.

Data analysis

Data were described through frequency tables, mean, SD, absolute frequency, and relative frequency. Data normality was tested through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which showed that all variables had non-normal distribution. Consequently, the Mann-Whitney U, Wilcoxon, and chi-square tests were used for data analysis. SPSS version 16 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis.

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1399.091). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles provided by the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education. In the sample selection process, the purpose and method of research were explained to the patients; then, they were invited to participate in the study, and the written and oral informed consent form was completed by them. This study was also registered on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials website (code: IRCT20200824048499N1).

Results

The means of participants’ age were, respectively, 67.57±4.62 and 67.08±4.62 in the intervention and control groups. Most participants in the intervention and control groups were married (73% vs 77%), and their educational level was below diploma (63% vs 67%). There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of participants’ age, gender, height, weight, educational level, marital status, number of children, living arrangement, source of income, family financial status, and history of affliction by serious illnesses (Table 2).

Life satisfaction and functional independence

Study groups did not significantly differ from each other regarding the pretest mean scores of functional independence and life satisfaction (P>0.05). The mean score of functional independence in both groups and the mean score of life satisfaction in the control group did not significantly change after the intervention (P>0.05).

However, the mean score of life satisfaction significantly increased in the intervention group after the intervention (P=0.001), but it was not significantly different in the control group. Accordingly, the between-group difference regarding the posttest mean score of functional independence was not significant (P=0.92), while the posttest mean score of life satisfaction was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group (P=0.001). Also, the results of the intra-group comparison after the intervention showed that the functional independence and life satisfaction in the intervention group had significant changes, while there was no change in the control group (P<0.05; Table 3).

Discussion

This study evaluated the effects of FCEM-based self-care education on functional independence and life satisfaction among community-dwelling older adults. The findings showed that FCEM-based self-care education had no significant effect on functional independence but significantly improved life satisfaction among older adults. The significant positive effect of FCEM-based self-care education on life satisfaction in the present study is in agreement with the findings of several previous studies (23, 26-28). The involvement of family members in self-care education programs is a good strategy to improve self-care and life satisfaction. Different factors can affect life satisfaction among older adults. For example, a study showed that participation in social activities provides older adults with more social opportunities, gives them a sense of significance and self-efficacy, and thereby improves their life satisfaction (23, 29).

Another study also reported that healthy lifestyle education based on physical exercise, balanced sleep, and stress management had significant effects on older adults’ life satisfaction. This research confirms that it is possible to increase their happiness and life satisfaction with the active participation of the elderly in healthy lifestyle education programs. Educational programs in health centers should be directed to attract the participation of the elderly in making decisions and carrying out prevention or health promotion programs. Such interventions should be continued in addition to involving them. In this case, compared to the interventions that health professionals decide, plan, and carry out, they have more satisfactory results (1). On the other hand, older adults with high life satisfaction consider age-related problems and disabilities inevitable and hence, feel capable of doing self-care activities and more seriously engaging in these activities (2). Therefore, self-care education programs, particularly family-centered programs, are essential to improve older adults’ self-care abilities and life satisfaction. Older people are more focused on family relationships and long-term success, unlike young people who emphasize more on social status and money. Physical health is an important factor in maintaining life satisfaction, but in old age, mental health seems to be a more fundamental factor than physical health in realizing this feeling. Physical health, socio-economic status, and social relationships all play important roles in the elderly population's overall life satisfaction (3).

Our findings also showed that FCEM-based self-care education had no significant effects on older adults’ functional independence. This finding agrees with the findings of 2 former studies (4, 5) but contradicts the findings of 2 other studies. The insignificant effects of our intervention on functional independence may be due to factors such as differences in older adults’ perceptions of self-care, the considerable effects of the CPVID-19 pandemic on their physical and mental conditions, self-care activities, and functional status. Moreover, changing the functional status of older adults needs long-term interventions, and its effects may appear after a long period of time. Therefore, more studies are needed to evaluate the effects of long-term self-care education on older adults’ functional independence.

On the other hand, the results of some studies have shown the positive effect of education on the level of functional independence. For instance, a study was conducted to investigate the effects of a healthy lifestyle program on the physical activity of older adults. The results of this study indicated that such a program, which encompasses physical self-care, can improve functional independence. However, this finding differs from the results of the present study (6). Also, in another study, the results of the implementation of the family empowerment model showed that family empowerment improves lifestyle and self-efficacy, which is not consistent with the present study. The inconsistency of the results of these studies with the current study can be due to the fact that the self-care training in the present study was focused on all aspects of self-care and was not one-dimensional; thus, it seems that more time is needed to stabilize the training and its effect on the functional independence of the elderly (7).

One of the limitations of the present study is the probable negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on participants’ desire to participate in the study and attend educational sessions. Of course, we attempted to overcome this limitation by holding educational sessions in open areas and with social distancing.

Conclusion

FCEM-based self-care education is effective in significantly improving life satisfaction among community-dwelling older adults. Providing self-care education to older adults and empowering their families to support their self-care activities can improve their health and the quality of elderly care. Further studies are recommended to evaluate the effects of long-term self-care education on functional independence. The findings of the present study can be used to design and use strategies for health promotion and family empowerment among older adults to improve their life satisfaction.

Acknowledgement

We are deeply grateful to the older adults who participated in the present study. We would like to thank the Research Administration of this university and the authorities of comprehensive health care centers in the south of Tehran, Iran.

Funding sources

This study was funded and supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 50602).

Clinical trial registration

https://fa.irct.ir; Date of clinical trial registration: 14/09/2020; code: IRCT20200824048499N1

Ethical statement

This protocol study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1399.091). This study was also registered on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials website (code: IRCT20200824048499N1).

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has a conflict of interest to declare.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed significantly to this study. T.M.M., Sh.N., and Sh.P. designed the project, performed the data collection, and wrote the manuscript, F.Sh. analyzed data, Sh.P. supervised execution of the study and data collection, and Sh.P. and Sh.N. also supervised the study. All the authors approved the content of the manuscript.

Aging is associated with different changes in different body systems. Musculoskeletal changes (such as muscular atrophy) alter walking and reduce mobility. Neurological, dermatological, urinary, and cardiopulmonary changes (such as reduced cardiac capacity, myocardial contractility, and cardiac output) are also very common among older adults.

Age-related changes reduce cognitive, mental, and functional abilities, increase older adults’ dependence on others, weaken social support, and lead to loneliness and acute and chronic health problems (1, 2). Reduced functional abilities and increased dependence on others are, in turn, associated with the development of different disabilities, hospitalization, increased health care costs and caregiver burden, and death (3, 4). Evidence shows that 1.3% of older adults over 65 years live alone. Loneliness can aggravate problems in doing daily activities and increase the risk of social isolation (4). A study reported that dependence on doing daily activities increases the sense of loneliness and insecurity and causes fears over communicating with family members (3). Contrarily, older adults with independence in their activities feel greater self-esteem, self-confidence (5), self-control, self-worth, and life satisfaction (6).

Dependency in older adults can significantly affect their life satisfaction. Life satisfaction is a cognitive component of subjective well-being and refers to individuals’ judgment about life as a whole. High levels of life satisfaction promote successful coping with different life conditions and age-related limitations and, thereby, give older adults a sense of happiness (7). Life satisfaction is determined by many different factors, such as independence, healthy lifestyle, and lifestyle education. A study reported that independence and participation in social activities provide older adults with more social opportunities, give them a sense of significance and self-efficacy, and improve their life satisfaction (8). Another study found that healthy lifestyle education based on physical exercise, sleep-activity balance, and stress management had significantly positively affected life satisfaction (9).

Self-care is a significant factor affecting independence and life satisfaction (10). Self-care refers to the ability to perform activities to prevent illness, maintain and promote health, and cope with illnesses and disabilities (11). Self-care in older adults is affected by age-related problems, such as physical and mental problems and disabilities (12). A study reported that self-care limitations are five times more prevalent among older adults with chronic illnesses (13). Another study showed poor self-care ability among 98% of older adults (14). Moreover, older adults who live alone have a lower desire for engagement in self-care activities (15). Therefore, older adults need support, particularly family support, to actively engage in self-care activities. A study reported that family support can increase older adults’ desire and motivation for doing self-care activities (16).

Self-care education is a method with potentially positive effects on self-care. A systematic method for self-care education is education based on the family-centered empowerment model (FCEM). FCEM was introduced in 2002 by Alhani to empower the family system for health promotion. The main steps of this model are perceived threat, problem-solving, educational participation, and evaluation (17). This model has so far been used in different studies on patients with myocardial infarction (18), asthma (19), and other chronic diseases (20). Most previous studies on self-care among older adults have focused on those with chronic illnesses (20, 21), and there are limited data about self-care and healthy lifestyles among community-dwelling older adults (22). The present study sought to narrow this gap. The study aimed to determine the effects of FCEM-based self-care education on functional independence and life satisfaction among community-dwelling older adults.

Methods

Design

This randomized clinical trial was conducted on community-dwelling older adults from July to October 2021.

Participants and setting

A total of 126 eligible older adults were recruited from local sociocultural centers using a convenience sampling method in District 6 of Tehran City, Iran. Inclusion criteria were the age of 60-75 years, living with a spouse or children, having no participation in self-care–related educational programs in the past year, having the ability to speak Persian, and having a family member with the ability to participate in educational sessions. Participants were excluded if they developed acute health problems, were hospitalized, or had 2 consecutive absences from the intervention sessions. They were randomly allocated into control (A) and intervention (B) groups via block randomization with a block size of 4. Accordingly, 6 possible blocks were designed and numbered 1-6 as follows: 1) AABB, 2) ABAB, 3) ABBA, 4) BBAA, 5) BABA, and 6) BAAB. Then, a randomization sequence was generated using an online randomizer (ie, www.randomization.com). For allocation concealment, each generated sequence was written on a card, and the card was put in an opaque bag. Bags were randomly selected during sampling, and participants were allocated to groups using the sequences in the bags. Participants did not know whether they were in the intervention or control group. The present study was a double-blind study that blinding was performed for a person who gave a statistical analysis.

The sample size was calculated with a confidence level of 0.95, power of 0.90, and satisfaction mean score of 16.02±4.22 in the intervention group and 12.13±4.15 in the control group (23). Accordingly, the sample size calculation formula showed that 50 persons per group were needed. Nonetheless, the sample size was increased to 63 per group to compensate for probable attrition.

N1 = [(Zα/2 + Zβ)2 × (σ1 + σ2)]/ (μ1 - μ2)2

A total of 126 older adults were recruited to the study and allocated to two 63-person groups. One participant from the intervention group and 2 participants from the control group were excluded due to voluntary withdrawal. Data analysis was performed on the data obtained from 62 participants in the intervention group and 61 participants in the control group (Figure 1).

Outcomes and instruments

The primary outcomes were life satisfaction and functional independence. Data collection instruments were a demographic questionnaire, Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (Katz ADL Index), and Zest Life Satisfaction Index. The demographic checklist included age, gender, height, weight, educational level, marital status, number of children, living arrangement, source of income, family financial status, home type, affliction by serious illnesses, and medication use.

The Katz ADL Index was used for functional independence assessment. This index assesses functional independence in 8 areas: bathing, toileting, continence, feeding, dressing, transferring, personal grooming, and walking. Items are scored as follows: 0, dependent; 1, needs help; and 2, “independent.” Therefore, the possible total score of the index is 0-16, which is interpreted as follows: scores 0-7, dependent; scores 8-11, needs help; and scores 12-16, independent (24). A study in Iran reported a content validity index of more than 0.82. Convergent validity showed that the mean scores of ADL and IADL in elderly individuals with normal and adverse normal cognitive abilities were significantly different. Also, the studied instruments were able to differentiate between different age groups. The sensitivity and specificity of ADL and IADL were 0.75 and 0.96, respectively. Cronbach α and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were more than 0.75 (24).

The Zest Life Satisfaction Index was used for life satisfaction assessment. This index has 13 positively and negatively worded items. Positively worded items are scored as follows: 0, I don’t know; 1, disagree; and 2, agree. Negatively worded items are scored as follows: 0, I don’t know; 2, disagree; and 1, agree. The possible total score of the index is 0-26, with higher scores showing higher life satisfaction. A study in Iran confirmed that the index has acceptable validity and reliability through the known-group comparison method and a Cronbach α of 0.79. The item-total correlation and test-retest confirmed its reliability, too (25).Participants completed the study instruments through the self-report method at 2 time points, namely, before and 8 weeks after the study intervention.

Intervention

The study intervention was FCEM-based self-care education in physical, mental, social, and spiritual dimensions. The main focus of the study intervention was on active and healthy lifestyles. The intervention was implemented based on the 4 steps of FCEM, namely, perceived threat, problem-solving, educational participation, and evaluation. Education was provided in six 1.5-hour weekly sessions (Table 1) using the lecture, question-and-answer, and group discussions. Participants received education in small groups (9 groups of 7 participants) and had active participation in the educational sessions through role-playing and experience sharing. Since the research setting was a sociocultural center and the elderly came to spend their free time, for this reason, they were not familiar with each other, and the possibility of contamination bias was minimized. Randomization also helped to reduce this bias. The control group received education routinely provided in the study setting in addition to a single self-care education session and an educational pamphlet.

Data analysis

Data were described through frequency tables, mean, SD, absolute frequency, and relative frequency. Data normality was tested through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which showed that all variables had non-normal distribution. Consequently, the Mann-Whitney U, Wilcoxon, and chi-square tests were used for data analysis. SPSS version 16 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis.

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1399.091). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles provided by the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education. In the sample selection process, the purpose and method of research were explained to the patients; then, they were invited to participate in the study, and the written and oral informed consent form was completed by them. This study was also registered on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials website (code: IRCT20200824048499N1).

Results

The means of participants’ age were, respectively, 67.57±4.62 and 67.08±4.62 in the intervention and control groups. Most participants in the intervention and control groups were married (73% vs 77%), and their educational level was below diploma (63% vs 67%). There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of participants’ age, gender, height, weight, educational level, marital status, number of children, living arrangement, source of income, family financial status, and history of affliction by serious illnesses (Table 2).

Life satisfaction and functional independence

Study groups did not significantly differ from each other regarding the pretest mean scores of functional independence and life satisfaction (P>0.05). The mean score of functional independence in both groups and the mean score of life satisfaction in the control group did not significantly change after the intervention (P>0.05).

However, the mean score of life satisfaction significantly increased in the intervention group after the intervention (P=0.001), but it was not significantly different in the control group. Accordingly, the between-group difference regarding the posttest mean score of functional independence was not significant (P=0.92), while the posttest mean score of life satisfaction was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group (P=0.001). Also, the results of the intra-group comparison after the intervention showed that the functional independence and life satisfaction in the intervention group had significant changes, while there was no change in the control group (P<0.05; Table 3).

Discussion

This study evaluated the effects of FCEM-based self-care education on functional independence and life satisfaction among community-dwelling older adults. The findings showed that FCEM-based self-care education had no significant effect on functional independence but significantly improved life satisfaction among older adults. The significant positive effect of FCEM-based self-care education on life satisfaction in the present study is in agreement with the findings of several previous studies (23, 26-28). The involvement of family members in self-care education programs is a good strategy to improve self-care and life satisfaction. Different factors can affect life satisfaction among older adults. For example, a study showed that participation in social activities provides older adults with more social opportunities, gives them a sense of significance and self-efficacy, and thereby improves their life satisfaction (23, 29).

Another study also reported that healthy lifestyle education based on physical exercise, balanced sleep, and stress management had significant effects on older adults’ life satisfaction. This research confirms that it is possible to increase their happiness and life satisfaction with the active participation of the elderly in healthy lifestyle education programs. Educational programs in health centers should be directed to attract the participation of the elderly in making decisions and carrying out prevention or health promotion programs. Such interventions should be continued in addition to involving them. In this case, compared to the interventions that health professionals decide, plan, and carry out, they have more satisfactory results (1). On the other hand, older adults with high life satisfaction consider age-related problems and disabilities inevitable and hence, feel capable of doing self-care activities and more seriously engaging in these activities (2). Therefore, self-care education programs, particularly family-centered programs, are essential to improve older adults’ self-care abilities and life satisfaction. Older people are more focused on family relationships and long-term success, unlike young people who emphasize more on social status and money. Physical health is an important factor in maintaining life satisfaction, but in old age, mental health seems to be a more fundamental factor than physical health in realizing this feeling. Physical health, socio-economic status, and social relationships all play important roles in the elderly population's overall life satisfaction (3).

Our findings also showed that FCEM-based self-care education had no significant effects on older adults’ functional independence. This finding agrees with the findings of 2 former studies (4, 5) but contradicts the findings of 2 other studies. The insignificant effects of our intervention on functional independence may be due to factors such as differences in older adults’ perceptions of self-care, the considerable effects of the CPVID-19 pandemic on their physical and mental conditions, self-care activities, and functional status. Moreover, changing the functional status of older adults needs long-term interventions, and its effects may appear after a long period of time. Therefore, more studies are needed to evaluate the effects of long-term self-care education on older adults’ functional independence.

On the other hand, the results of some studies have shown the positive effect of education on the level of functional independence. For instance, a study was conducted to investigate the effects of a healthy lifestyle program on the physical activity of older adults. The results of this study indicated that such a program, which encompasses physical self-care, can improve functional independence. However, this finding differs from the results of the present study (6). Also, in another study, the results of the implementation of the family empowerment model showed that family empowerment improves lifestyle and self-efficacy, which is not consistent with the present study. The inconsistency of the results of these studies with the current study can be due to the fact that the self-care training in the present study was focused on all aspects of self-care and was not one-dimensional; thus, it seems that more time is needed to stabilize the training and its effect on the functional independence of the elderly (7).

One of the limitations of the present study is the probable negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on participants’ desire to participate in the study and attend educational sessions. Of course, we attempted to overcome this limitation by holding educational sessions in open areas and with social distancing.

Conclusion

FCEM-based self-care education is effective in significantly improving life satisfaction among community-dwelling older adults. Providing self-care education to older adults and empowering their families to support their self-care activities can improve their health and the quality of elderly care. Further studies are recommended to evaluate the effects of long-term self-care education on functional independence. The findings of the present study can be used to design and use strategies for health promotion and family empowerment among older adults to improve their life satisfaction.

Acknowledgement

We are deeply grateful to the older adults who participated in the present study. We would like to thank the Research Administration of this university and the authorities of comprehensive health care centers in the south of Tehran, Iran.

Funding sources

This study was funded and supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 50602).

Clinical trial registration

https://fa.irct.ir; Date of clinical trial registration: 14/09/2020; code: IRCT20200824048499N1

Ethical statement

This protocol study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1399.091). This study was also registered on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials website (code: IRCT20200824048499N1).

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has a conflict of interest to declare.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed significantly to this study. T.M.M., Sh.N., and Sh.P. designed the project, performed the data collection, and wrote the manuscript, F.Sh. analyzed data, Sh.P. supervised execution of the study and data collection, and Sh.P. and Sh.N. also supervised the study. All the authors approved the content of the manuscript.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. Nguyen C, Leanos S, Natsuaki MN, Rebok GW, Wu R. Adaptation for growth via learning new skills as a means to long-term functional independence in older adulthood: Insights from emerging adulthood. Gerontologist. 2020;60(1):4-11. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

2. Rodríguez‐Gómez I, Mañas A, Losa‐Reyna J, Rodríguez‐Mañas L, Chastin SF, Alegre LM, et al. Prospective changes in the distribution of movement behaviors are associated with bone health in the elderly according to variations in their frailty levels. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35(7):1236-45. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

3. Chang SH, Yu C-l, Chen M-c. Building a cohesive partnership: Perspectives of staff caregivers on improving self-care independence among older adults living in long-term care facilities. Journal of Aging and Long-Term Care. 2018;1(3):101-7. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

4. Hattori S, Yoshida T, Okumura Y, Kondo K. Effects of reablement on the independence of community-dwelling older adults with mild disability: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(20):3954. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

5. Toledano-González A, Labajos-Manzanares T, Romero-Ayuso D. Well-being, self-efficacy and independence in older adults: a randomized trial of occupational therapy. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;83:277-84. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

6. Şahin DS, Özer Ö, Yanardağ MZ. Perceived social support, quality of life and satisfaction with life in elderly people. Educational Gerontology. 2019;45(1):69-77. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

7. Khodabakhsh S. Factors affecting life satisfaction of older adults in Asia: A systematic review. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2022;23(3):1289-304. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

8. Qin W, Xu L, Sun L, Li J, Ding G, Wang Q, et al. Association between frailty and life satisfaction among older people in Shandong, China: the differences in age and general self‐efficacy. Psychogeriatrics. 2020;20(2):172-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

9. Phulkerd S, Thapsuwan S, Chamratrithirong A, Gray RS. Influence of healthy lifestyle behaviors on life satisfaction in the aging population of Thailand: a national population-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):43. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

10. Tzeng H-M. Older Adults' Demographic Social Determinants of Organizing Personal Healthcare Self-Care. Medsurg Nursing. 2020;29(5):321-6,342. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

11. Xiang X, Freedman VA, Shah K, Hu RX, Stagg BC, Ehrlich JR. Self-reported vision impairment and subjective well-being in older adults: a longitudinal mediation analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(3):589-95. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

12. Wong AKC, Bayuo J, Wong FKY, Yuen WS, Lee AYL, Chang PK, et al. Effects of a nurse-led telehealth self-care promotion program on the quality of life of community-dwelling older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(3):e31912. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

13. Iovino P, De Maria M, Matarese M, Vellone E, Ausili D, Riegel B. Depression and self‐care in older adults with multiple chronic conditions: a multivariate analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(7):1668-78. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

14. Tabrizi JS, Behghadami MA, Saadati M, Söderhamn U. Self-care ability of older people living in urban areas of northwestern Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47(12):1899-905. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google scholar]

15. Vicente MC, Silva CRRd, Pimenta CJL, Bezerra TA, Lucena HKVd, Valdevino SC, et al. Functional capacity and self-care in older adults with diabetes mellitus. Aquichan. 2020;20(3):1-11. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

16. David D, Dalton J, Magny-Normilus C, Brain MM, Linster T, Lee SJ. The quality of family relationships, diabetes self-care, and health outcomes in older adults. Diabetes Spectr. 2019;32(2):132-8. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

17. Atashzadeh-Shoorideh H, Arshi S, Atashzadeh-Shoorideh F. The effect of family-centered empowerment model on the life style, self-efficacy and HbA1C of diabetic patients. Iranian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism (IJEM). 2017;19(4):244-51. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

18. Vahedian-Azimi A, Alhani F, Goharimogaddam K, Madani S, Naderi A, Hajiesmaeili M. Effect of family-centered empowerment model on the quality of life in patients with myocardial infarction: A clinical trial study. Journal of Nursing Education (JNE). 2015;4(1):8-22. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

19. Rajabi R, Forozy M, Fuladvandi M, Eslami H, Asadabady A. The effect of family-centered empowerment model on the knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy of mothers of children with asthma. Journal of Nursing Education (JNE). 2016;5(4):41-50. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

20. Alhani F, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Norouzzadeh R, Rahimi-Bashar F, Vahedian-Azimi A, Jamialahmadi T, et al. The effect of family-centered empowerment model on the quality of life of adults with chronic diseases: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;316:140-7. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

21. Isac C, Lee P, Arulappan J. Older adults with chronic illness-caregiver burden in the Asian context: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(12):2912-21. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

22. Mjøsund HL, Moe CF, Burton E, Uhrenfeldt L. Integration of Physical Activity in reablement for community dwelling older adults: a systematic scoping Review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1291-315. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

23. Mehr MM, Zamani-Alavijeh F, Hasanzadeh A, Fasihi T. Effect of healthy lifestyle educational programs on happiness and life satisfaction in the elderly: a randomized controlled trial study. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2019;13(4):440-51. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

24. Taheri Tanjani P, Azadbakht M. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the activities of daily living scale and instrumental activities of daily living scale in elderly. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2016;25(132):103-12. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

25. Tagharrobi Z, Tagharrobi L, Sharifi K, Sooki Z. Psychometric evaluation of the Life Satisfaction Index-Z (LSI-Z) in an Iranian elderly sample. Payesh. 2011;10(1):5-13. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

26. Masoodi R, Soleimani MA, Alhani F, Rabiei L, Bahrami N, Esmaeili SA. Effects of family-centered empowerment model on perceived satisfaction and self concept of multiple sclerosis patients care givers. Koomesh. 2013;14(2):240-8. [View at Publisher] [Google scholar]

27. Parry SW, Bamford C, Deary V, Finch TL, Gray J, MacDonald C, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy-based intervention to reduce fear of falling in older people: therapy development and randomised controlled trial-the Strategies for Increasing Independence, Confidence and Energy (STRIDE) study. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(56):1-206. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

28. Toots A, Littbrand H, Lindelöf N, Wiklund R, Holmberg H, Nordström P, et al. Effects of a high‐intensity functional exercise program on dependence in activities of daily living and balance in older adults with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):55-64. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

29. Ng ST, Tey NP, Asadullah MN. What matters for life satisfaction among the oldest-old? Evidence from China. PloS one. 2017;12(2):e0171799. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google scholar]

30. Nyandra M, Kartiko BH, Susanto PC, Supriyati A, Suryasa W, Susanto PC. Education and training improve quality of life and decrease depression score in elderly population. Eurasian Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 2018;13(2). [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |