Volume 20, Issue 2 (10-2023)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2023, 20(2): 54-57 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Gorzin M, Behnampour N, Ziaei T. Comparison of self-awareness and sexual satisfaction scores before and during the COVID-19 in married women covered by health centers in 2020. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2023; 20 (2) :54-57

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1416-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1416-en.html

1- Counseling and Reproductive Health Research Center, Azadshahr Health Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

2- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Health, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

3- Counseling and Reproductive Health Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran ,tayebe.ziaee@yahoo.com

2- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Health, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

3- Counseling and Reproductive Health Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 450 kb]

(658 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2034 Views)

Full-Text: (267 Views)

Introduction

The implementation of social distancing measures was widely adopted as a key strategy in preventing the spread of COVID-19. During the pandemic, the fear of contracting the virus or transmitting it to others was identified as a significant source of stress (1-6). Amidst social distancing measures, concerns were raised about how to maintain sexual intimacy and satisfaction, given that physical proximity is typically a prerequisite for sexual relations between couples (7). Sexual satisfaction, which is often regarded as a crucial aspect of quality of life, can serve as a supportive factor against health-related issues (8). A lack of sexual satisfaction can lead to marital problems, conflicts, incompatibility and result in negative interactions and unhappiness among couples (9). Indeed, sexual satisfaction can help couples better navigate challenges and has a significant impact on their mental health (10).

Evidence suggests that sexual satisfaction can be influenced by several key factors, including the level of self-awareness (11, 12). Self-awareness skills enable individuals to identify their own characteristics that can influence their sexual satisfaction (12, 13). Self-aware individuals are cognizant of their own attributes, both positive and negative, strengths and weaknesses, values, expectations, and personal desires. They are also capable of recognizing shifts in their thoughts and emotions and can take corrective action when necessary (14). Two dimensions of self-awareness, namely private self-awareness and social anxiety, have distinct impacts on sexual satisfaction. Private self-awareness can enhance sexual satisfaction, while social anxiety can potentially decrease it (11).

According to some research, while there has been a significant rise in sexual desire and the frequency of sexual activities during the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been observed that the quality of sexual life has markedly deteriorated (15). On the other hand, some studies have shown that for individuals who engaged in sexual activity 1-5 times per week prior to the pandemic, there was no significant difference in the frequency of sexual activity during the week before and during the epidemic. However, for individuals who engaged in sexual activity more than five times per week prior to the pandemic, an upward trend in the frequency of sexual relations was observed during this period (16). Some other studies suggested a correlation between the COVID-19 pandemic and a decline in both sexual activity frequency and libido (17).

Today, researchers and healthcare providers concur that the mental and emotional facets of sexual well-being constitute one of the most crucial aspects of an individual’s sexual health (18). Given the unprecedented circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic and the social isolation resulting from infection control measures, it remains unclear how self-awareness and sexual satisfaction among couples have been affected. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the scores of self-awareness and sexual satisfaction before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among married women covered by health service centers in Gorgan, Iran.

Methods

The average scores of sexual satisfaction and self-awareness from initial study [1], which was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (11, 14), were compared with the scores obtained of the current study carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study population comprised all women of reproductive age who covered by health service centers. The participants were through census method from 76 women who had participated in initial study. All participants from the initial study were contacted via phone calls and invited to participate in the current study by completing an online questionnaire. Sixty women who agreed to participate in the study were included in this research.

The criteria for inclusion in the current study were participation in previous research and the willingness to participate in the current project. The sole exclusion criterion was the participant’s unavailability. In order to collect data, the Persian version of the Self-Consciousness Scale (SCS), the Persian version of the Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS), and a demographic profile questionnaire were used (all tools were similar to the first study).

Self-Consciousness Scale (SCS):

The SCS scale is comprised of 24 items, each evaluated using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” (4) to “strongly disagree” (0). This scale is divided into three categories of private self-awareness, public self-awareness, and social anxiety. Items 1, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 17, 19, 20, and 24 pertain to private self-awareness, items 3, 8, 13, 16, 18, and 22 pertain to public self-awareness, and items 2, 4, 6, 9, 14, 15, 21, and 23 pertain to social anxiety. Items 3, 7, 9, 11, 14, and 23 are reverse-scored. The scale has a minimum score of zero and a maximum score of 96, with an average score of 48. A score within or below the average range indicates low self-awareness, while a score above the average suggests high self-awareness. In a study by Ziaei et al. (2018), the reliability coefficient of the scale was estimated at 0.68, based on the Cronbach's alpha method (14), and in current study it was 0.74.

Hudson’s Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS):

This index contains 25 items, which are rated on a five-point Likert scale. The response options include “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “most of the time”, and “always”. Each item is scored from one (“never”) to five (“always”). However, items with a negative connotation (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 18, 20, 24, and 25) are reverse scored to ensure accurate interpretation of the results. The scale scores span from a minimum of 25 to a maximum of 125. A score above 100 suggests high sexual satisfaction. In the study conducted by Ziaei et al. (2018), the reliability coefficient of this scale was determined to be 0.79, as measured by the Cronbach’s alpha method (11), and in current study it was 0.82.

After contacting the participants from the initial study, those who met the eligibility criteria and provided their consent were sent a link to the online questionnaires. This link was delivered via messaging platforms, such as Telegram or WhatsApp. For three of the participants who were unable to complete the online questionnaires, the survey was administered in person.

Data analysis was performed in SPSS Version 16. The mean scores of the two groups were evaluated at three separate intervals, using a repeated measures ANOVA test for comparison. Within each group, Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was utilized to compare the average scores at two consecutive time points. To compare the two groups at the evaluated intervals, Tukey’s test was employed. The pretest score from the initial study was designated as the first time point, the post-test score from the same study was considered the second time point, and the score obtained in the current study, conducted during the COVID-19 period, was recognized as the third time point. The significance level of the tests was set at 0.05.

Results

Out of 76 women who participated in the primary survey, 60 women (31 from the intervention group and 29 from the control group) were included in the current study. In the intervention group, 45.2% of the participants and in the control group, 48.3% had an education level above a high school diploma. The participants in the intervention group had an average age of 35.9±6.39 years, while those in the control group had an average age of 35.31±7.07 years. The average age of women in the two groups did not show a significant difference.

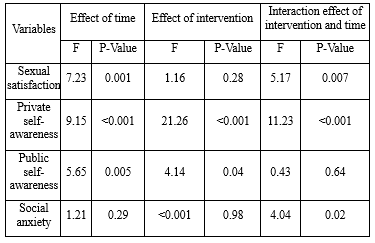

The mean scores of sexual satisfactions were compared using Fisher’s test, with the assumption of sphericity confirmed according to Mauchly’s test (P=0.61). As shown in Table 1, the changes in the sexual satisfaction score were not identical in the intervention and control groups throughout the study (indicating the presence of a group-time interaction), and they were statistically significant (P=0.007). Based on the findings, the intervention could significantly increase the sexual satisfaction score of the participants (P=0.001). In the intervention group, the average score of sexual satisfaction changed significantly in the first and second intervals. However, there were no significant changes in the control group in any interval. Although no significant difference was found between the groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the score of sexual satisfaction remained higher among women in the intervention group, compared to the control group.

Additionally, Fisher’s test was utilized to compare the mean scores of private self-awareness, under the assumption of sphericity as confirmed by Mauchly’s test (P=0.054). According to Table 1, the changes in the private self-awareness score did not exhibit the same pattern in the two groups throughout the study (indicating the presence of a group-time interaction), and these changes were statistically significant (P<0.001). The intervention significantly enhanced the private self-awareness score of the participants (P=0.001). The average score of private self-awareness in the intervention group showed significant changes in the first, second, and third time points. Although there was no significant difference between the groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the private self-awareness score remained higher among women in the intervention group, compared to the control group.

Furthermore, Fisher's test was used to compare the average scores of public self-awareness, with the sphericity assumption confirmed based on Mauchly’s test (P=0.6). According to the results, the changes in the public self-awareness score exhibited similar patterns in the two groups throughout the study (indicating no group-time interaction effect), and these changes were not statistically significant (P=0.64). The intervention significantly increased the public self-awareness score of the participants (P=0.005). In the between-group analysis, the main effect of group was significant (P=0.04) (Table 1). The average score of public self-awareness exhibited a significant change in the intervention group between the first and second intervals. Nevertheless, there were no significant changes in the control group in any interval. Overall, the two groups showed no significant difference in terms of the average public self-awareness score across the three evaluated time points.

Moreover, the mean scores of social anxieties were compared using the Greenhouse-Geisser statistic, following the rejection of the Sphericity hypothesis as per Mauchly’s test (P=0.04). The changes in the social anxiety score did not exhibit the same pattern in the two groups throughout the study (indicating the presence of a group-time interaction effect), and these changes were statistically significant (P=0.02). Based on the results, the intervention could not change the social anxiety score of the participants (P=0.29). According to the between-group analysis, the main effect of group was not significant (P=0.98) (Table 1). The average score of social anxiety significantly changed in the intervention group between the first and second intervals. On the other hand, no significant change was observed in the control group in any interval. Overall, a significant difference was observed in the average social anxiety scores between the two groups over the three time periods assessed (P=0.02) (Table 2).

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the average scores of self-awareness and sexual satisfaction of women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results indicated that the average sexual satisfaction score of women significantly changed in the intervention group during the first and second intervals. Conversely, no significant changes were observed within the control group at any time point. Overall, a significant difference was observed in the average scores of sexual satisfactions between the intervention and control groups across all three evaluated time points. While there was no significant difference between the groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the women in the intervention group consistently had higher sexual satisfaction scores than those in the control group. It can be inferred that the acquisition of self-awareness skills enabled women to attain a higher sexual satisfaction score during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the control group without a history of acquiring such skills.

In the present study, the observed decline in sexual satisfaction compared to the pre-COVID-19 period among women with self-awareness skills could be attributed to various factors, such as an increased likelihood of interpersonal conflicts, high stress levels, disregard for personal privacy, medical issues, and heightened focus on the disease, its symptoms, and preventive methods. Other contributing factors could be the alarming statistics related to COVID-19 fatalities and the fear of disease transmission, which might divert attention away from oneself, family, and marital relationship.

In this regard, Arafat et al. reported that individuals who engaged in sexual activity with their spouse 1-5 times a week prior to the COVID-19 pandemic did not experience a significant change in the frequency of their sexual activity. However, for those who had sex more than five times a week, the sexual intercourse frequency increased during the pandemic (16). Also, in a study by Panzeri et al., despite the psychological challenges posed by the pandemic, most couples did not observe any changes in their sexual satisfaction or sexual intercourse when compared to the pre-COVID-19 period (19). The findings of these two studies do not align with those of the present study. On the other hand, another study demonstrated that the COVID-19 period was associated with a decrease in both the frequency of sexual activity and libido (17), which is consistent with our findings. In a study by Gauvin et al., the participants reported a slight reduction in their sexual satisfaction and the frequency of orgasms compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there were no significant differences in the level of sexual distress or satisfaction. Based on their findings, there was an improvement in women’s sexual performance, while no significant difference was observed in men’s performance. Nevertheless, the changes in sexual health and satisfaction were not significant (20). Additionally, a review study by Bagheri et al. indicated a decline in both sexual satisfaction and performance among couples during the COVID-19 outbreak. The study suggested that many couples reduced the frequency of their sexual activities due to stress and fear of contracting the virus. Moreover, there was a significant increase in marital conflicts among families during the COVID-19 outbreak. This escalation in conflicts ultimately led to a decrease in both sexual satisfaction and performance of couples; these findings align with the results of the present study (21). Reduced sexual satisfaction has been found to correlate with the frequency of sexual activity and the level of intimate relationship satisfaction. A study that began at the onset of the pandemic and continued for the subsequent 18 months demonstrated that the stress triggered by the pandemic was not just an initial response. Instead, it persisted over time, leading to changes in sexual satisfaction. These changes were accompanied by decreased intimacy in relationships and a reduced frequency of sexual encounters (22). Meanwhile, a study by Rogowska et al. found no direct correlation between sexual satisfaction and the degree of restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic (23). A study by Minaei Moghadam et al. corroborated that the fear induced by COVID-19 had detrimental effects on the sexual performance of married individuals, particularly women, thereby diminishing the quality of their marital life (24). In another study carried out in Luxembourg, it was observed that sexual issues escalated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and sexual satisfaction experienced a decline compared to the period prior to the enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions (25). Two significant factors that influenced the changes observed during the COVID-19 pandemic were the level of education and occupation (26). Some researchers have posited that individuals who are more informed or educated exhibited greater fear and adhered more strictly to social distancing measures. Consequently, these individuals experienced heightened sexual dysfunction and reduced sexual activity (27-29).

Research indicates that individuals’ occupations underwent significant changes during the COVID-19 era, which had a substantial impact on their sexual health. A significant number of people were forced to modify their work routines to accommodate working from home, while others had to navigate additional risks in their workplace. These changes had a profound impact on people’s sexual health, particularly for those who were unemployed, became unemployed during this period, or were healthcare workers. Overall, the increased stress levels associated with these changes could be a potential contributing factor (27, 29-31). Gönenç et al. addressed another factor affecting sexual satisfaction. They concluded that sexual issues stemming from the fear of COVID-19 negatively influenced women’s sexual quality of life. They suggested that healthcare professionals address the fear of COVID-19 and its associated sexual problems during the course of the pandemic (32).

Regarding the three domains of self-awareness, it was observed that the average score of private self-awareness significantly changed in the intervention group in three distinct intervals. Additionally, the present study found that the average scores of private self-awareness exhibited a significant difference between the intervention and control groups at the three evaluated time points. Despite the absence of a significant difference between the two groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the private self-awareness score consistently remained higher in the intervention group compared to the control group.

Moreover, the present study revealed that the average score of public self-awareness significantly changed in the intervention group in the first and second intervals. On the other hand, no significant changes were observed in the control group in any interval. Similarly, the two groups showed no significant difference in the average score of public self-awareness at the three investigated time points. Even though there was no significant difference between the two groups during the COVID-19 period, the public self-awareness score continued to be higher in the intervention group compared to the control group. Also, the average score of social anxiety significantly changed in the intervention group at the first and second time points. Conversely, no significant changes were detected in the control group at any of the evaluated time points. Based on the present findings, there was a significant difference in the average social anxiety score of women between the groups in the three investigated intervals.

In line with the findings of the current study regarding changes in self-awareness, Soylu et al. noted that the quarantine period and home confinement due to COVID-19 significantly impacted mental health crises, such as feelings of hopelessness, alterations in self-awareness, and perceived limitations in physical abilities (33). Some studies have corroborated that the crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic can induce significant stress and elevate anxiety levels across various age, educational, and occupational groups. Among the suggested coping strategies are enhancing health self- awareness, practicing mindfulness, and engaging in home exercises (2, 3, 5, 6, 33-38).

Conclusion

In the present study, despite the lack of a significant difference between the two groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the score of sexual satisfaction, private self-awareness and public self-awareness of women in the intervention group remained higher than that of the control group. However, during the COVID-19 period, the average social anxiety score showed an increase in the intervention group compared to the period before COVID-19 (second time of study), but it did not reach to the score of the first time. This finding indicates that the transformations brought about by training and counseling have been ingrained and have not completely dissipated. This is evident as, despite the rise in social anxiety in the intervention group during the COVID-19 era, their level of sexual satisfaction, private self-awareness and public self-awareness remained higher than that of the control group.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the Research Deputy of Golestan University of Medical Sciences, and all women for their cooperation.

Funding sources

This project supported by Golestan University of Medical Sciences. The authors received no financial support for the authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical statement

The ethical principles including confidentiality and protection of the personal information of the participants were observed in the research. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1399.301)

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed significantly to this study. Ziaei and Gorzin designed the project and wrote the manuscript, Gorzin performed the data collection, Behnampour analyzed data, Ziaei also supervised the study. All the authors approved the content of the manuscript.

The implementation of social distancing measures was widely adopted as a key strategy in preventing the spread of COVID-19. During the pandemic, the fear of contracting the virus or transmitting it to others was identified as a significant source of stress (1-6). Amidst social distancing measures, concerns were raised about how to maintain sexual intimacy and satisfaction, given that physical proximity is typically a prerequisite for sexual relations between couples (7). Sexual satisfaction, which is often regarded as a crucial aspect of quality of life, can serve as a supportive factor against health-related issues (8). A lack of sexual satisfaction can lead to marital problems, conflicts, incompatibility and result in negative interactions and unhappiness among couples (9). Indeed, sexual satisfaction can help couples better navigate challenges and has a significant impact on their mental health (10).

Evidence suggests that sexual satisfaction can be influenced by several key factors, including the level of self-awareness (11, 12). Self-awareness skills enable individuals to identify their own characteristics that can influence their sexual satisfaction (12, 13). Self-aware individuals are cognizant of their own attributes, both positive and negative, strengths and weaknesses, values, expectations, and personal desires. They are also capable of recognizing shifts in their thoughts and emotions and can take corrective action when necessary (14). Two dimensions of self-awareness, namely private self-awareness and social anxiety, have distinct impacts on sexual satisfaction. Private self-awareness can enhance sexual satisfaction, while social anxiety can potentially decrease it (11).

According to some research, while there has been a significant rise in sexual desire and the frequency of sexual activities during the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been observed that the quality of sexual life has markedly deteriorated (15). On the other hand, some studies have shown that for individuals who engaged in sexual activity 1-5 times per week prior to the pandemic, there was no significant difference in the frequency of sexual activity during the week before and during the epidemic. However, for individuals who engaged in sexual activity more than five times per week prior to the pandemic, an upward trend in the frequency of sexual relations was observed during this period (16). Some other studies suggested a correlation between the COVID-19 pandemic and a decline in both sexual activity frequency and libido (17).

Today, researchers and healthcare providers concur that the mental and emotional facets of sexual well-being constitute one of the most crucial aspects of an individual’s sexual health (18). Given the unprecedented circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic and the social isolation resulting from infection control measures, it remains unclear how self-awareness and sexual satisfaction among couples have been affected. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the scores of self-awareness and sexual satisfaction before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among married women covered by health service centers in Gorgan, Iran.

Methods

The average scores of sexual satisfaction and self-awareness from initial study [1], which was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (11, 14), were compared with the scores obtained of the current study carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study population comprised all women of reproductive age who covered by health service centers. The participants were through census method from 76 women who had participated in initial study. All participants from the initial study were contacted via phone calls and invited to participate in the current study by completing an online questionnaire. Sixty women who agreed to participate in the study were included in this research.

The criteria for inclusion in the current study were participation in previous research and the willingness to participate in the current project. The sole exclusion criterion was the participant’s unavailability. In order to collect data, the Persian version of the Self-Consciousness Scale (SCS), the Persian version of the Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS), and a demographic profile questionnaire were used (all tools were similar to the first study).

Self-Consciousness Scale (SCS):

The SCS scale is comprised of 24 items, each evaluated using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” (4) to “strongly disagree” (0). This scale is divided into three categories of private self-awareness, public self-awareness, and social anxiety. Items 1, 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 17, 19, 20, and 24 pertain to private self-awareness, items 3, 8, 13, 16, 18, and 22 pertain to public self-awareness, and items 2, 4, 6, 9, 14, 15, 21, and 23 pertain to social anxiety. Items 3, 7, 9, 11, 14, and 23 are reverse-scored. The scale has a minimum score of zero and a maximum score of 96, with an average score of 48. A score within or below the average range indicates low self-awareness, while a score above the average suggests high self-awareness. In a study by Ziaei et al. (2018), the reliability coefficient of the scale was estimated at 0.68, based on the Cronbach's alpha method (14), and in current study it was 0.74.

Hudson’s Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS):

This index contains 25 items, which are rated on a five-point Likert scale. The response options include “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “most of the time”, and “always”. Each item is scored from one (“never”) to five (“always”). However, items with a negative connotation (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 18, 20, 24, and 25) are reverse scored to ensure accurate interpretation of the results. The scale scores span from a minimum of 25 to a maximum of 125. A score above 100 suggests high sexual satisfaction. In the study conducted by Ziaei et al. (2018), the reliability coefficient of this scale was determined to be 0.79, as measured by the Cronbach’s alpha method (11), and in current study it was 0.82.

After contacting the participants from the initial study, those who met the eligibility criteria and provided their consent were sent a link to the online questionnaires. This link was delivered via messaging platforms, such as Telegram or WhatsApp. For three of the participants who were unable to complete the online questionnaires, the survey was administered in person.

Data analysis was performed in SPSS Version 16. The mean scores of the two groups were evaluated at three separate intervals, using a repeated measures ANOVA test for comparison. Within each group, Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was utilized to compare the average scores at two consecutive time points. To compare the two groups at the evaluated intervals, Tukey’s test was employed. The pretest score from the initial study was designated as the first time point, the post-test score from the same study was considered the second time point, and the score obtained in the current study, conducted during the COVID-19 period, was recognized as the third time point. The significance level of the tests was set at 0.05.

Results

Out of 76 women who participated in the primary survey, 60 women (31 from the intervention group and 29 from the control group) were included in the current study. In the intervention group, 45.2% of the participants and in the control group, 48.3% had an education level above a high school diploma. The participants in the intervention group had an average age of 35.9±6.39 years, while those in the control group had an average age of 35.31±7.07 years. The average age of women in the two groups did not show a significant difference.

The mean scores of sexual satisfactions were compared using Fisher’s test, with the assumption of sphericity confirmed according to Mauchly’s test (P=0.61). As shown in Table 1, the changes in the sexual satisfaction score were not identical in the intervention and control groups throughout the study (indicating the presence of a group-time interaction), and they were statistically significant (P=0.007). Based on the findings, the intervention could significantly increase the sexual satisfaction score of the participants (P=0.001). In the intervention group, the average score of sexual satisfaction changed significantly in the first and second intervals. However, there were no significant changes in the control group in any interval. Although no significant difference was found between the groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the score of sexual satisfaction remained higher among women in the intervention group, compared to the control group.

Additionally, Fisher’s test was utilized to compare the mean scores of private self-awareness, under the assumption of sphericity as confirmed by Mauchly’s test (P=0.054). According to Table 1, the changes in the private self-awareness score did not exhibit the same pattern in the two groups throughout the study (indicating the presence of a group-time interaction), and these changes were statistically significant (P<0.001). The intervention significantly enhanced the private self-awareness score of the participants (P=0.001). The average score of private self-awareness in the intervention group showed significant changes in the first, second, and third time points. Although there was no significant difference between the groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the private self-awareness score remained higher among women in the intervention group, compared to the control group.

Furthermore, Fisher's test was used to compare the average scores of public self-awareness, with the sphericity assumption confirmed based on Mauchly’s test (P=0.6). According to the results, the changes in the public self-awareness score exhibited similar patterns in the two groups throughout the study (indicating no group-time interaction effect), and these changes were not statistically significant (P=0.64). The intervention significantly increased the public self-awareness score of the participants (P=0.005). In the between-group analysis, the main effect of group was significant (P=0.04) (Table 1). The average score of public self-awareness exhibited a significant change in the intervention group between the first and second intervals. Nevertheless, there were no significant changes in the control group in any interval. Overall, the two groups showed no significant difference in terms of the average public self-awareness score across the three evaluated time points.

|

Table 1. The effect of time, intervention and the interaction of them on the scores of sexual satisfaction, private and public self-awareness, and social anxiety

|

Table 2. The repeated measures ANOVA test of sexual satisfaction in two groups at the investigated times |

This study aimed to compare the average scores of self-awareness and sexual satisfaction of women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results indicated that the average sexual satisfaction score of women significantly changed in the intervention group during the first and second intervals. Conversely, no significant changes were observed within the control group at any time point. Overall, a significant difference was observed in the average scores of sexual satisfactions between the intervention and control groups across all three evaluated time points. While there was no significant difference between the groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the women in the intervention group consistently had higher sexual satisfaction scores than those in the control group. It can be inferred that the acquisition of self-awareness skills enabled women to attain a higher sexual satisfaction score during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the control group without a history of acquiring such skills.

In the present study, the observed decline in sexual satisfaction compared to the pre-COVID-19 period among women with self-awareness skills could be attributed to various factors, such as an increased likelihood of interpersonal conflicts, high stress levels, disregard for personal privacy, medical issues, and heightened focus on the disease, its symptoms, and preventive methods. Other contributing factors could be the alarming statistics related to COVID-19 fatalities and the fear of disease transmission, which might divert attention away from oneself, family, and marital relationship.

In this regard, Arafat et al. reported that individuals who engaged in sexual activity with their spouse 1-5 times a week prior to the COVID-19 pandemic did not experience a significant change in the frequency of their sexual activity. However, for those who had sex more than five times a week, the sexual intercourse frequency increased during the pandemic (16). Also, in a study by Panzeri et al., despite the psychological challenges posed by the pandemic, most couples did not observe any changes in their sexual satisfaction or sexual intercourse when compared to the pre-COVID-19 period (19). The findings of these two studies do not align with those of the present study. On the other hand, another study demonstrated that the COVID-19 period was associated with a decrease in both the frequency of sexual activity and libido (17), which is consistent with our findings. In a study by Gauvin et al., the participants reported a slight reduction in their sexual satisfaction and the frequency of orgasms compared to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there were no significant differences in the level of sexual distress or satisfaction. Based on their findings, there was an improvement in women’s sexual performance, while no significant difference was observed in men’s performance. Nevertheless, the changes in sexual health and satisfaction were not significant (20). Additionally, a review study by Bagheri et al. indicated a decline in both sexual satisfaction and performance among couples during the COVID-19 outbreak. The study suggested that many couples reduced the frequency of their sexual activities due to stress and fear of contracting the virus. Moreover, there was a significant increase in marital conflicts among families during the COVID-19 outbreak. This escalation in conflicts ultimately led to a decrease in both sexual satisfaction and performance of couples; these findings align with the results of the present study (21). Reduced sexual satisfaction has been found to correlate with the frequency of sexual activity and the level of intimate relationship satisfaction. A study that began at the onset of the pandemic and continued for the subsequent 18 months demonstrated that the stress triggered by the pandemic was not just an initial response. Instead, it persisted over time, leading to changes in sexual satisfaction. These changes were accompanied by decreased intimacy in relationships and a reduced frequency of sexual encounters (22). Meanwhile, a study by Rogowska et al. found no direct correlation between sexual satisfaction and the degree of restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic (23). A study by Minaei Moghadam et al. corroborated that the fear induced by COVID-19 had detrimental effects on the sexual performance of married individuals, particularly women, thereby diminishing the quality of their marital life (24). In another study carried out in Luxembourg, it was observed that sexual issues escalated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and sexual satisfaction experienced a decline compared to the period prior to the enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions (25). Two significant factors that influenced the changes observed during the COVID-19 pandemic were the level of education and occupation (26). Some researchers have posited that individuals who are more informed or educated exhibited greater fear and adhered more strictly to social distancing measures. Consequently, these individuals experienced heightened sexual dysfunction and reduced sexual activity (27-29).

Research indicates that individuals’ occupations underwent significant changes during the COVID-19 era, which had a substantial impact on their sexual health. A significant number of people were forced to modify their work routines to accommodate working from home, while others had to navigate additional risks in their workplace. These changes had a profound impact on people’s sexual health, particularly for those who were unemployed, became unemployed during this period, or were healthcare workers. Overall, the increased stress levels associated with these changes could be a potential contributing factor (27, 29-31). Gönenç et al. addressed another factor affecting sexual satisfaction. They concluded that sexual issues stemming from the fear of COVID-19 negatively influenced women’s sexual quality of life. They suggested that healthcare professionals address the fear of COVID-19 and its associated sexual problems during the course of the pandemic (32).

Regarding the three domains of self-awareness, it was observed that the average score of private self-awareness significantly changed in the intervention group in three distinct intervals. Additionally, the present study found that the average scores of private self-awareness exhibited a significant difference between the intervention and control groups at the three evaluated time points. Despite the absence of a significant difference between the two groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the private self-awareness score consistently remained higher in the intervention group compared to the control group.

Moreover, the present study revealed that the average score of public self-awareness significantly changed in the intervention group in the first and second intervals. On the other hand, no significant changes were observed in the control group in any interval. Similarly, the two groups showed no significant difference in the average score of public self-awareness at the three investigated time points. Even though there was no significant difference between the two groups during the COVID-19 period, the public self-awareness score continued to be higher in the intervention group compared to the control group. Also, the average score of social anxiety significantly changed in the intervention group at the first and second time points. Conversely, no significant changes were detected in the control group at any of the evaluated time points. Based on the present findings, there was a significant difference in the average social anxiety score of women between the groups in the three investigated intervals.

In line with the findings of the current study regarding changes in self-awareness, Soylu et al. noted that the quarantine period and home confinement due to COVID-19 significantly impacted mental health crises, such as feelings of hopelessness, alterations in self-awareness, and perceived limitations in physical abilities (33). Some studies have corroborated that the crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic can induce significant stress and elevate anxiety levels across various age, educational, and occupational groups. Among the suggested coping strategies are enhancing health self- awareness, practicing mindfulness, and engaging in home exercises (2, 3, 5, 6, 33-38).

Conclusion

In the present study, despite the lack of a significant difference between the two groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, the score of sexual satisfaction, private self-awareness and public self-awareness of women in the intervention group remained higher than that of the control group. However, during the COVID-19 period, the average social anxiety score showed an increase in the intervention group compared to the period before COVID-19 (second time of study), but it did not reach to the score of the first time. This finding indicates that the transformations brought about by training and counseling have been ingrained and have not completely dissipated. This is evident as, despite the rise in social anxiety in the intervention group during the COVID-19 era, their level of sexual satisfaction, private self-awareness and public self-awareness remained higher than that of the control group.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the Research Deputy of Golestan University of Medical Sciences, and all women for their cooperation.

Funding sources

This project supported by Golestan University of Medical Sciences. The authors received no financial support for the authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical statement

The ethical principles including confidentiality and protection of the personal information of the participants were observed in the research. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Ethical code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1399.301)

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed significantly to this study. Ziaei and Gorzin designed the project and wrote the manuscript, Gorzin performed the data collection, Behnampour analyzed data, Ziaei also supervised the study. All the authors approved the content of the manuscript.

[1] “Assessing the impact of individual counseling based on self-awareness skills on the sexual satisfaction of women attending health service centers in Gorgan during 2016”

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Midwifery

References

1. Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang YT, Liu Z, Hu S, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e17-8. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Shahyad SH, Mohammadi MT. Psychological impacts of Covid-19 outbreak on mental health status of society individuals: a narrative review. Journal of Military Medicine. 2020;22(2):184-92. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

3. Rubin GJ, Wessely S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. BMJ. 2020;368:m313. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. Social capital and sleep quality in individuals who self-isolated for 14 days during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in January 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e923921. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

5. Yang L, Wu D, Hou Y, Wang X, Dai N, Wang G, et al. Analysis of psychological state and clinical psychological intervention model of patients with COVID-19. MedRxiv. 2020:PPR118682. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

6. Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e21. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Pascoal PM, Narciso ID, Pereira NM. What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people's definitions. J Sex Res. 2014;51(1):22-30. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Amadian F, Haghayegh SA. Relationship model between sexual dissatisfaction and quality of life in married obese patients with mediating role of marital intimacy. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci. 2020;28(1). [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Zarenezhad H, Hosini M, Rahmati A. Relationships between sexual assertiveness and sexual dissatisfaction with couple burnout through the mediating role of marital conflict. Family Counseling and Psychotherapy. 2019;9(1):197-216. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

10. Nasiri Deh Sourkhi R, Mousavi SF. The study of some correlative of sexual satisfaction and marital satisfaction in married women of Esfahan City. Rooyesh. 2015;4(2):135-52. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

11. Ziaei T, Gorzin M, Rezaei Aval M, Behnampour N. The effect of Individual Self-awareness Skills' based Counseling on Correlation between Self-awareness and Sexual Satisfaction of Women at Reproductive age. Iranian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 2018;6(5):57-63. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

12. Ziaei T, Gorzin M, Rezai M, Behnampour N. The effect of individual consciousness skills' base counseling on sexual satisfaction of women at reproductivef age. J Res Dev Nurs Midw. 2018;15(2):22-7. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

13. Mohammadkhani SH FL, Mootabi F, Kazemzadeh Atoofi M, Fata L. Life Skills Training, Students, Teacher Handbook: DanJeh; 1385:51-60.

14. Ziaei T, Gorzin M, Aval MR, Behnampour N. Effectiveness of Self-awareness based Individual counseling on self-awareness of women in reproductive age. World Family Medicine Journal. 2018;6(1):35-40. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

15. Yuksel B, Ozgor F. Effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on female sexual behavior. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;150(1):98-102. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Arafat SY, Alradie-Mohamed A, Kar SK, Sharma P, Kabir R. Does COVID-19 pandemic affect sexual behaviour? A cross-sectional, cross-national online survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113050. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

17. Szuster E, Kostrzewska P, Pawlikowska A, Mandera A, Biernikiewicz M, Kałka D. Mental and Sexual Health of Polish Women of Reproductive Age During the COVID-19 Pandemic-An Online Survey. Sex Med. 2021;9(4):100367. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

18. Deutsch AR, Hoffman L, Wilcox BL. Sexual self-concept: Testing a hypothetical model for men and women. J Sex Res. 2014;51(8):932-45. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

19. Panzeri M, Ferrucci R, Cozza A, Fontanesi L. Changes in sexuality and quality of couple relationship during the Covid-19 lockdown. Front Psychol. 2020;11:565823. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. Gauvin SEM, Mulroy ME, McInnis MK, Jackowich RA, Levang SL, Coyle SM, et al. An Investigation of Sexual and Relationship Adjustment During COVID-19. Arch Sex Behav. 2022;51(1):273-85. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

21. Bagheri Sheykhangafshe F, Fathi-Ashtiani A. The Role of Marital Satisfaction and Sexual Satisfaction during the Coronavirus 2019 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Families. Journal of Family Research. 2021;17(1):45-62. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

22. Dion J, Hamel C, Prévost B, Bergeron-Leclerc C, Pouliot E, Maltais D, et al. Stressed and distressed: how is the COVID-19 pandemic associated with sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction? J Sex Med. 2023;20(2):152-60. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

23. Rogowska AM, Wójcik N, Janik A, Klimala P. Is there a direct link between sexual satisfaction and restrictions during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13):7769. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

24. Minaei Moghadam S, Namdar P, Mafi M, Yekefallah L. A Survy between Fear of COVID-19 Disease and Sexual Function of Iranian Married Men and Women Living in Qazvin: A Descriptive Study. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2022;21(1):33-48. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

25. Fischer VJ, Bravo RG, Brunnet AE, Michielsen K, Tucker JD, Campbell L, et al. Sexual satisfaction and sexual behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the International Sexual Health And REproductive (I-SHARE) health survey in Luxembourg. BMC Public Health. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. de Oliveira L, Carvalho J. Women's Sexual Health During the Pandemic of COVID-19: Declines in Sexual Function and Sexual Pleasure. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2021;13(3):76-88. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

27. Culha MG, Demir O, Sahin O, Altunrende F. Sexual attitudes of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Impot Res. 2021;33(1):102-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

28. Karakas LA, Azemi A, Simsek SY, Akilli H, Esin S. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2021;152(2):226-30. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

29. Karsiyakali N, Sahin Y, Ates HA, Okucu E, Karabay E. Evaluation of the sexual functioning of individuals living in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic: an internet-based nationwide survey study. Sex Med. 2021;9(1):100279. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

30. De Rose AF, Chierigo F, Ambrosini F, Mantica G, Borghesi M, Suardi N, et al. Sexuality during COVID lockdown: a cross-sectional Italian study among hospital workers and their relatives. Int J Impot Res. 2021;33(1):131-6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

31. Schiavi MC, Spina V, Zullo MA, Colagiovanni V, Luffarelli P, Rago R, et al. Love in the Time of COVID-19: Sexual Function and Quality of Life Analysis During the Social Distancing Measures in a Group of Italian Reproductive-Age Women. J Sex Med. 2020;17(8):1407-13. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

32. Gönenç IM, Öztürk Özen D, Yılmaz Sezer N. The relationship between fear of covid-19, quality of sexual life, and sexual satisfaction of women in turkey. Int J Sex Health. 2022;34(3):377-85. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

33. Soylu Y. The psychophysiological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in the college students. Physical Education of Students. 2021;25(3):158-63. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

34. Eyni S, Ebadi M, Hashemi Z. Corona Anxiety in Nurses: The Predictive Role of Perceived Social Support and Sense of Coherence. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2020;26(3):320-31. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

35. Shakerinasab M, Zibaei Sani M, Kazemabadi Farahani Z, Ghalehnovi Z. The relationship between perceived stress and social anxiety with psychological cohesion in pandemic crises, with emphasis on Covid 19 patients discharged from Sabzevar Vasei Hospital. Journal of Clinical Psycology. 2021;13(2):87-96. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

36. Pu B, Zhang L, Tang Z, Qiu Y. The Relationship between Health Consciousness and Home-Based Exercise in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5693. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

37. solgi z. The Effect of Metacognitive Skills Training on Symptoms of Social Anxiety and Demoralization Symptoms In girls With High levels of Coronary Anxiety. Quarterly Social Psychology Research. 2022;11(44):1-22. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

38. Sweeny K, Rankin K, Cheng X, Hou L, Long F, Meng Y, et al. Flow in the time of COVID-19: Findings from China. PloS One. 2020;15(11):e0242043. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |