BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-1062-en.html

2- Research Center for Nursing and Midwifery Care, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

3- Nursing and Midwifery College. Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

4- Nursing and Midwifery College. Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iram

Introduction

In the USA more than 234000 cases of breast cancer would be diagnosed annually. Breast cancer constitutes 25% of the new cases of cancer among women. In 2012, 1.7 million new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed all around the world (1). In Asia, due to the changes in fertility pattern and lifestyle, the incidence of breast cancer has been constantly increasing over the time. For example in Korea, age-specific incidence of breast cancer among women of 45 to 49 years old has been tripled to 140 cases in every 100000 women (2, 3). During the past decade, the incidence of breast cancer has been increased by 30% in China and India. In Iran also breast cancer is the most common cancer among women; Iranian women would be affected by breast cancer at least a decade sooner than their fellow women living in developed countries (4). According to the latest official report by the Iranian Cancer Registry of Ministry of Health and Medical Education, the age-standardized incidence of breast cancer was reported to be 28.25. The age-standardized incidence of breast cancer in Yazd, which is located in the center of Iran, is reported to be 38.52 (5). Movahedi et al. (2012) reported that the five-year survival rate of breast cancer in Iran is 71% while this rate is increased to 85% in developed countries (6). One of the main reasons for increased rate of mortality by breast cancer among Iranian women is few referrals for monitoring and delayed visits to physicians (7). Therefore early diagnosis of breast cancer using mammography could probably decrease the rate of mortality and improve the survival rate (8). In Iran 70% of women would refer to physicians during the advanced stages of the disease when it is too late for treatment (9). Results of a qualitative study showed that psychological factors like embarrassment, fear of the diagnosis of cancer, preoccupation with underlying diseases, the need for having a companion, internalizing the experiences of others and misunderstanding about mammography and maladaptive coping patterns like avoidance and denial, religious beliefs and belief in fate were some of the obstacles for performing mammography (10). Elabaid et al. (2014) reported that although the national monitoring program for breast cancer was conducted in the UAE for free based on the international framework for monitoring, but the rate of referrals was only 10% and about 65% of the patients would refer during advanced stages of the disease. In this study 44.1% of women who had never performed mammography stated that they had no information about the methods of monitoring (11). Cultural and social barriers would vary in different countries and is specific to every region (12). For monitoring breast cancer in developing countries, it is recommended to design educational interventions based on theories (13). Trans theoretical Model (TTM) would be a helpful framework for monitoring for breast cancer screening using mammography. The TTM has a stage construct and would suggest that changes would occur over time and people would pass stages like pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance to change their behaviors; other constructs of this model include self-efficacy, the balance of decision–making and also the processes of change (14). Self-efficacy means having sufficient self-esteem to overcome obstacles. The balance of decision-making is like the process of weighing the strengths and weaknesses to adapt a new behavior against an old behavior. Using the processes of change could be helpful in understanding the occurrence of change in people (15). The findings of the study for evaluating the stages of change for adapting monitoring behaviors for breast cancer among Korean women showed that most of them (50.8%) were in the stage of action/maintenance, and only 2.6% were in the stage of relapse. (16). Results of the study showed that most of Iranian women (40%) were in the stage of pre-contemplation, and only 5.8% were in the stage of maintenance (17). After a literature review, it was revealed that few studies were conducted on Iranian women based on the framework of the TTM and considering the prevalence of breast cancer among women in Yazd. This study aimed to determine the predicting factors of mammography adherence among Iranian women based on TTM. Results of the present study could be helpful in developing educational programs for improving preventive behaviors of breast cancer, encouraging women to be more sensitive about their breast health, in-time diagnosis of probable cancer and desirably controlling it.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 300 married women in Yazd in 2018. Cluster sampling was done from health centers of Yazd. Each of the urban health centers (4 centers) were considered as a cluster and random sampling was conducted in each cluster. Tabachnick and Fidell (2013) proposed using formula of “50+8m” where “m” is the number of predictors (18). This study considered 300 subjects with coefficient of determination equals to 2 to apply regression model that are sufficiently accurate to represent the parameters in the targeted population. The qualified women were allocated randomly to each cluster (n=75).

After conducting a pilot study for evaluating the reliability of the questionnaire, from the medical records of the families under coverage of the health center some were randomly selected and women who lived at the same region were contacted. If a visiting date was set for women, they were called and asked to come to the center. The inclusion criteria were being female, being 40 years old or more, willingness to participate in the study, being a native residence of Yazd, speaking Farsi, being able to read and write, not having breast cancer and not having psychiatric disorders. The exclusion criteria were unwillingness to participate in the study, moving to another city or region for living.

Considering lack of a reliable and valid Farsi questionnaire based on TTM for evaluating women’s in mammography behaviors, by reviewing articles, a native questionnaire was developed to evaluate the constructs of TTM.

Data gathering tool was a questionnaire which included demographic information, history of breast diseases, history of taking mammography: reasons for having a mammography, reasons for not having a mammography (no physician’s advice, not calling to remind for the mammography, unawareness, harmfulness of mammography for health), showing the results of mammography to the specialist, age at the first mammography, and the method of preference for reminding the next mammography visits (phone call, massage, written invitation), decision-making steps for performing mammography questionnaire, self-efficacy scale; in this part the participants would face questions that would challenge their ability to perform a mammography. In this part women would answer questions with a 4-point Likert scale from “not sure” to “completely sure”, the balance of decision-making scale. This scale includes 6 questions about the pros and 11 questions about the cons. These questions were answered with a 4-point scale from “totally agree” to “totally disagree”. The change process questionnaire; this part included 20 questions about the processes of change in behaviors related to mammography. In this study both groups of experimental and cognitive processes were regarded. 4-points Likert scale from “totally agree” to “totally disagree” was used for answering this part.

The validity of the questionnaires was approved through face and content validity. Qualitative and quantitative methods were used for approving content validity. For determining the internal consistency of the questionnaire, it was given to 15 to 30 women referred to the selected health centers and the Cronbach’s α was calculated; values more than 0.7 were considered acceptable. In this study, Cornbrash's alpha of this questionnaire was 0.94. Data were analyzed in SPSS statistics for windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, III., USA) using chi-square test, Spearman correlation coefficient, one-way analysis of variance, and regression analysis with a significant level of α = 0.05. Regarding the questions of process of change, self-efficacy and balance of decision-making, the range of scores for each participant was divided by the number of questions; so each participant’s mean score was calculated. The range of score for the self-efficacy construct was 8 to 32. For ranking the level of self-efficacy, based on their gained scores, participants were divided into three groups of poor (8-15), moderate (16-23) and good (24-32). To determine the balance of decision-making, the score of perceived barriers was subtracted for the score of perceived benefits.

Ethical issues including getting permission from the research council of the university for conducting the study, providing sufficient information to every participant about the study, assuring the participants about confidentiality of their information and voluntarily participation in the study, were regarded. All the participants signed a written informed consent.

Results

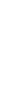

The mean age of women was 47.25±6.97 years old (ranged from 40 to 70). The majority of them were housewives (84.3%), and had health insurance (93%), only 15.7% of them were employed. Regarding their educational level, 53% of them had an under-diploma degree, and 18.7% had college degrees. Mean score of studied women's age at the first mammography was 41.92  7.36. 55% of the women mentioned social media as the main source of gaining health information. 71% of the women preferred to be reminded about their mammography visit time through phone calls. The history of performing mammography in women is shown in Table 1. Results of the study regarding the stages of behavioral change showed that most of the participants (81.4%) were in inactive stages of decision-making for performing mammography (Pre-contemplation and contemplation) and only 8.3% of them were in active stages (action and maintenance) (Figure 1).

7.36. 55% of the women mentioned social media as the main source of gaining health information. 71% of the women preferred to be reminded about their mammography visit time through phone calls. The history of performing mammography in women is shown in Table 1. Results of the study regarding the stages of behavioral change showed that most of the participants (81.4%) were in inactive stages of decision-making for performing mammography (Pre-contemplation and contemplation) and only 8.3% of them were in active stages (action and maintenance) (Figure 1).

The mean scores of perceived advantages and barriers were 21.26±3.33 and 25.03±7.90 respectively. The mean score of decisional balance was 3.76±9.89. According to the results, the mean score of the process of change was 59.73±10.59 and it was separately 39.37±6.56 and 20.36±4.71 respectively for cognitive processes and behavioral processes. Spearman correlation coefficient showed that performing mammography had a positive correlation with stages of decision-making and self-efficacy constructs and had a negative correlation with perceived barriers and decisional balance constructs (p=0.01) (Table 2).

The most important barriers for not performing mammography among the participants were stated as not having enough time because of their job (85.6%), uncertainty of having privacy during the mammography (81.6%), not having the means of transportation for visiting the mammography center (81%), not having an companion for going to the mammography center (79.7%) and lack of time for having different problems in life (76.4%).

The mean score of self-efficacy among the women was 24.54±6.5. 62.7% of the participant had good self-efficacy, 24.3% had moderate self-efficacy and 13% had poor self-efficacy for performing mammography. One-way analysis of variance showed that the score of self-efficacy at the stage of maintenance was significantly higher than its score at other stages and was significantly lower at the stage of pre-contemplation than other stages.

|

Table 1. Frequency distribution of participants for mammography adoption

|

|

Table 2. Correlation matrix of all TTM constructs

|

According to linear regression test, the validity of the predicting TTM by all of its constructs together was 47% and among them, the role of the changes process construct was significantly more than other constructs. The predicting power of the changes process construct was 0.661 (Table 3). Chi square test showed a significant difference in different stages of behavioral change for performing mammography based on the variables of educational level, job and history of benign breast diseases (p<0.05).

|

Table 3. Regression analysis of TTM constructs as predictors of mammography adoption

|

Discussion

According to the results, only 13.3% of women had performed mammography for screening purposes. Therefore, the rate of performing mammography would be reported as very low and undesirable. Also most of the women (86.4%) were at inactive stages of decision-making (pre-contemplation and contemplation) for performing mammography. Results of a study by Hirai et al. (2013) on 641 Japanese women showed that 12.3% of them were at the stage of pre-contemplation, 22.2% at the contemplation stage, 13.7% at the action stage, 47.1% at the maintenance stage and 4.7% at the relapse stage. (19). It seems that the differences between the results of the present study and the mentioned study would be lack of a national and official program for breast cancer screening in Iran (20). In the study of Moodi et al. (2012), which was conducted in Isfahan to determine the distribution of the stages of behavioral changes for performing mammography, results showed that 57.3% of women were at inactive stage, only 21.1% were at active stage and 32.2% were at relapse stage (21); these results are similar to the results of the present study.

In the present study 55% of women mentioned mass media as the most important resource for gaining health information which is similar to the results of Ozmen et al. study (2016) (22); next ranks were allocated to other resources. The effect of multi-component informative campaigns of the mass media which would use different channels for data transfer has been approved in increasing the rate of women’s participation in screening for breast diseases (23). Results of a study by Hall (2015) showed that publication of health promotion messages through culture multi-component informative campaigns (radio and printed contents) has increased the rate of mammography among low-income African-American women (24).

Reminding the time of mammography through phone call was the first priority for the studied women. In the study of Goelen et al. (2010) it was revealed that 22% of the women in the intervention group has performed mammography after receiving the reminder phone call, which was 4% more than the women in the control group (25). According to the Icheku et al. (2015) research findings when it is difficult to reach women through phone, the best method to encourage women for mammography is to use a combination of written invitation and SMS (26). Both of these methods were mentioned in the present study.

Results of the present study showed that performing mammography had a positive correlation with steps of decision making and self-efficacy constructs and a negative correlation with perceived barriers and decisional balance constructs. Overall, 62.7% of the studied women had good self-efficacy for performing mammography. It is more likely for women with higher self-efficacy to perform mammography (27). A significant relation was observed between Iranian women’s self-efficacy and their mammography behavior in the study of Ahmadian et al. (2012) (28). In this study the mean score of self-efficacy of studied women at the maintenance stage was significantly higher than other stages and at pre-contemplation stage was significantly lower than other stages. In the study of Russel et al. (2007) also higher self-efficacy was observed at higher stages of decision-making for breast cancer screening (29).

The dominance of the perceived benefits construct over the perceived barriers construct was obvious in the present study which has created a significant negative correlation with behavior’s construct. The most important perceived barriers, which have also been mentioned in previous studies, were means of transportation in Documet et al. (2008) study (30) , lack of companion in Khodayarian et al. (2016) study (10), uncertainty of having privacy during mammography and provoking conservative thoughts in women’s mind about shamefulness of performing diagnostic measures on the breasts in Avci et al. study (2008) (31), lack of time due to life preoccupations in Hacihasanoglu et al. study (2008) (32), and not performing mammography due to time constraint caused by their job in Yao et al. study (2016) (33). Health educators, by using cultural measures appropriate for their society, should eliminate the barriers and emphasis on the main benefits of predictive behaviors for breast cancer.

Results of the regression analysis showed that constructs of the TTM, strongly, have the power to predict the mammography behavior of Iranian women. The process of change construct was able to predict 0.661 of the studied behavior. So it could be expected that changes in the stages of decision-making in studied women for performing mammography would lead to changes in their behavior. Generally, women who do not perform regular mammography are those who believe that they are not at risk for breast cancer (while, actually, they are at high risk for breast cancer) (34). Since most of the studied women were at inactive stages of decision-making, initially their level of perceived threat should be increased. Based on the stage of decision-making each individual is at, an appropriate intervention for that stage could be selected to improve the behavior. Therefore, the TTM could effectively be used to increase the participation of Yazdi women in mammography.

In the present study a significant relation was observed the variable of educational level and the process of change in a way that women with lower educational level were mostly at inactive stages of decision-making. Also, women who had a history of benign breast diseases were mostly in action and maintenance stages, similar to the results of the study by Moodi et al. (2012) (21). Results showed that most of the women as housewives (69.6%) were at pre-contemplation stage. Chi square test showed a significant difference in stages of change in the mammography behavior based on the participants’ job, similar to the results of the study by Ahmadian et al. (2012) (28).

One of the limitations of this study was that since this study was conducted on married 40-70 years old women, it could not be generalized for other age groups or divorced or widowed women. Another limitation was that since no similar tool based on the TTM with approved validity and reliability did not exists, predictive validity and concurrent validity were not evaluated, which is recommended to be evaluated in further studies.

Conclusion

Results of the present study showed that most of the women were at inactive stages of decision-making for mammography behavior and, based on the results, to improve the stages of the behavior, their self-efficacy should be improved. For this matter, it is suggested to design interventional programs like playing movies. Also, health educators could emphasis on the benefits of mammography like early diagnosis, keeping the breasts and decreased possibility of mortality due to the disease, through individual and group counseling and encourage women. Ministry of Health and Medical Education with the cooperation of medical universities should predict and take measures like insuring women at risk for developing breast cancer, mobile mammography for easy access to mammography by spending less time and making contracts with sports clubs to resolve the problem of inactivity among women.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our thanks to Research Council and Ethics Committee affiliated with Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran (IR.SSU.SPH.REC.1396.82), and all women participating in the study.

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |